The whale is the most astonishing animal the world has ever known. It does not merely inspire superlatives – it is a living superlative.

Jacques Cousteau, 1986

Meeting a Minke Whale

In late December 2015 a Minke Whale washed ashore at Ynyslas where the River Dyfi meets the sea. Information came filtering in through social media and we thought we’d take the rare opportunity to have a look. It was dark when we got to the beach and a fine drizzle came and went, softening, most of the time into a thin mist composed of droplets that swirled in the air with the waft of a hand.

We didn’t know the whale’s exact location but made an educated guess from the published photographs and crossed through the dunes onto the main beach. Very soon we only needed to follow our noses as the aroma of ripe whale was calling to us, loudly. Slowly the great brown mass began to appear in the light of our torches, which carved through the mist like giant light-sabres. We slowed our pace as we approached, as if we had blundered into a church, and, at the altar, was an open casket. It was humbling, in the extreme to stand in front of such a giant be-stilled beauty in the cold and dark, illuminating its details by torchlight that could not reach from one end of the animal to the other, such was the scale.

Preservation

Call me a weirdo, you won’t be the first, tell me to get stuffed, you won’t be the first, but the taxidermist in me did not want this treasure to go to waste, or, to put it another way, I felt a strong urge to do something with this experience. Maybe you won’t think me weird for that. At a very young age, I was taken to our local museum because I had read – or been read to – about bats and I wanted to see one. My family were new to the countryside so, instead of just walking out at dusk, we went off to the museum. It proved to be a big day for me; I was hooked. My passion was and always has been drawing wildlife but here in the museum there were animals frozen in time that could be looked at close-up and 3-dimensionally.

Not stuffed, but sculpted

For me, it was as good a wildlife experience as any other, there was no time limit, they wouldn’t run away, they were captured in just the way I wanted to capture my wildlife experiences. We went back to the museum again and again and eventually I was introduced to the resident taxidermist who would, several years later, become my boss, mentor and lifelong friend. He explained that taxidermy specimens are not ‘stuffed’, they are an art form, a sculpted body beneath a carefully preserved skin. He told me that, whilst many old museum specimens were shot by hunters, today museum specimens are brought in by members of the public who find them hit by cars, washed up on beaches or some other non-deliberate means. “This bird here,” he said, “died of flu. It flew into a window.”

Mum and I had already had a go at preserving butterflies so we were on a museum train of thought but this experience showed that every wildlife experience can be preserved somehow and that it was worthwhile and fun. I think a lot of people we meet are just like me and Mum were then; looking for a way to make something of what we see. If you are like us, you may not even know it, but it is possible to harbour a frustration that is not quite clear enough to grasp. Perhaps it is a desire to ‘capture’ nature experiences? I don’t want to state the obvious but sometimes it helps list things sometimes to clarify what we are thinking and where we are headed.

Preserving Nature

- Living animals and plants can be photographed and sketched. These methods provide proof that we actually saw the thing and sketching is a harmonious eye, to brain to hand to paper, and back to the eye, cycle that works very well for the human brain. I think that is what the cave painters were doing, capturing the things that delighted them most.

- I’m only rarely satisfied with my photographs or sketches and sometimes fail completely, so the next possibility is to research what we’ve seen, or want to see and prepare some sort of artwork that way. It doesn’t have to be 2 dimensional or visual. It could be a sculpture, rhyme or prose. Whatever it is, it makes the experience your own, you’ve done something with it, you have your trophy.

- Dead specimens can be treated exactly the same as above but offer other opportunities. The easy way out as well as the best way to preserve a specimens for scientific purposes is freezing or pickling. Whilst pickled specimens can make interesting or macabre curiosities I don’t think they fully satisfy the artist that dwells within all humans.

- Most mammal skins can be preserved either as study skins, ornaments or curiosities or as full realistic mounts. Their skeletons can also be preserved. The only hic-up with trying to preserve skin and skeleton is the claws or toe nails which have to go with one or the other. They can be replicated though and if we are being accurate, the claws belong with the skin and not with the skeleton.

- Exceptional mammals are whales and, to some extent, other hairless species such as pigs and primates. I’ll come back to these.

- Birds can be treated similarly to mammals but the beak (usually called the bill amongst pros) is much more conveniently dealt with if left attached to the skull which, with some surface sculpture after cleaning and preserving, is reinserted into the skin. Bird legs, the scaly clue that they are feathered reptiles, can be preserved or cast. Skeletal preparations of birds, in my experience, tend to come about when the skin is too badly damaged or decomposed.

- Reptiles and fish are inbetweeners in museum/preservation terms. They are also probably my speciality. Many ‘collectors’ want the actual skin preserving. It’s the proof thing again like a photo. You’ll see many taxidermy specimens of reptiles and fish in museums but I prefer casting. With fish, lizards, turtles and crocodilians it is all but impossible to separate the skin from the skull. The skull is tricky to clean and can shrink as it dries. The scales of these species are also inclined to fade (or turn brown) in colour and these too can shrink and distort. A cast however, preserves the exact shape of heads and scale faithfully. It may require painting (although not necessarily) but this is true of the skin too and a cast is easier to paint. Casting also leaves you withy the possibility of a skeleton too, it’s a win-win!

- Amphibians look horrendous as taxidermy specimens and beautiful as casts. Please prove me wrong and I will give you the appropriate praise.

- Invertebrates, comprising 95% of all living things, suit a variety of treatments depending on size, shape, softness or crustiness but I won’t go into all that now, I think you get the picture.

So there I was with this dead whale

You know you’re probably at least a little bit weird, if you are the only one there, with a dead whale, thinking, I wish I could keep it… is there a way, I could keep it?

Years ago when I was a taxidermist in training, a school of pilot whales washed-up, ironically, in the Wash. It’s called a stranding of course and these poor souls were almost certainly alive when they hit the sand, distraught panicking, they died in misery. My boss phoned the authorities and got permission to ‘collect’ one for the museum. They had, by this time been carted to a knackers yard. I was desperate to go with him, I usually did, but we had people coming in to collect loan specimens so I had to stay and cater to their needs. Normally it was a delight but on this one occasion I was a bit miffed.

Our museum like many others loaned out specimens free of charge to artists and educators. Among our visitors were quite famous artists, wildlife trust and similar educators and pest control officers. They would come in with a list and we would trundle down to the store rooms and hopefully we’d have what they wanted. Part of my job was cataloguing and organising the stores which were in disarray (my boss had just taken over the job of keeper of vertebrates, as well as being taxidermist). Another part was loaning the same specimens out. As it turned out, this was a great way to learn about and become familiar with world wildlife.

Anyway, while I was plodding back and forth to the store, my boss was gutting and de-fleshing a pilot whale whose bones he loaded into his own van which never smelled the same again. The following day we cleaned the bones up some more and began the preparation work. For most species this skilled work entails several phases of special chemicals. We arranged the skeleton on the floor as it would have been in life and stared at the bright red flesh on the stark white bones interspersed with more purplish muscle, ivory colour blubber and bits of black skin. This was my first ever work with a cetacean. My boss looked at the whale, looked at me and said…

“Let’s just bury it shall we”

Burying, as well as water masceration, are great ways to prepare large skeletons without flushing horrible chemicals into the environment… just let nature do it! The down side, if you’re that way inclined, is that the result doesn’t always have that sparkling, almost creamy appearance of a chemically prepared skeleton and, in the case of burying or entombing, you might have to deal with some soil or insect pupa cases.

So we buried it for later retrieval.

Big Blue

Pilot whales are big, but you couldn’t call them immense and they are not baleen (or filter-feeding) whales. I remember being blown away on my first visit to the BMNH (British Museum of Natural History which now tends to call itself The Natural History Museum), by the full size blue whale there.

I had been wowed by it in my animal encyclopaedia already but to be stood in front of one has a special effect. It is a bit like a movie on the big screen; you have to move your head to look at all of it and even then, much of it is in the distance or hidden behind its own immense mass. In the many halls and galleries of wonders, this is the one that really makes you feel small and that there really are greater things than yourself. It is hard to believe that what you are looking at is real. But it’s not real.

Blue whales themselves are real of course. Here’s how real…

- Growing to over 30 metres long and 190 tonnes in weight (about the weight of 2000 people) they are about as real as it is possible to be and they are (as far as we know) the largest animals there have ever been.

- Stand the jaw of a blue whale up like an arch, and most of the world’s dinosaurs would easily be able to walk under it. The largest animal there has ever been in Earth’s 4600 million years history, the weight of 25 elephants and the length of 4 buses bumper to bumper … All the more shameful for us that we have nearly wiped them out at least once and threaten to do so again.

- A newborn blue whale calf is about the same size as an adult Minke Whale and it grows faster than any other animal.

- The main blood vessels of an adult whale are pipes from the heart which are, famously, wide enough for a grown man to crawl through.

- Its 3 metre thick tongue, heavier than an elephant and, 3 metre long penis are legendary. My boss had a saucy sense of humour and told me that ,to circumcise a whale, it would take 4-skin divers due to the immense drawbacks of the operation.

- Blue whales are thought to live to about 90 years old. It’s easy to say ‘wow’ and move on but I hesitate here. There may be whales out there that are older than my parents and were born well before the second world war began. Whales that witnesses the clash of the Hood and the Bismarck may remember the event and there parents would have known comparatively silent seas, before they were full of motorised vessels and undersea mining.

But the BMNH blue whale is not real.

Can you imagine casting something that size? And imagine trying to get the body into a life-like position. Imagine trying to get its skin (which would have to be cured somewhere) over the immense made-to measure mannikin and then sewing it up without wrinkles or shrinkage. Imagine how annoyed everyone would be with each other.

My second museum boss was not a taxidermist but a curator. I was his taxidermist. He showed me a photograph of the BMNH blue whale being built. It was covered with people. Unlike the gory pictures of whales being deconstructed in whaling stations, this was a thing of beauty and seemed to be in worship of the blue whales immensity and importance. All those little folk working on that one animal, albeit an effigy, hit me harder than seeing the model itself. And that’s the additional museum method I was to get involved with. If you don’t have a dead specimen to work with, if it is too rare, extinct, to big or too complicated… you can always make a model, life-size, miniature or enlarged to get people face to face with your interpretation of it. Imagine making and enlarged model of a blue whale!

Go To The Natural History Museum

If you are in London, forget everything else, go to the Natural History Museum to see the blue whale. It was built in the 1930s when no photographs or usable descriptions of blue whales in their natural habitat existed. The brilliant taxidermist who did the work was Percy Stammwitz who used a comparatively lightweight frame covered with a wire-mesh screed which must have cut their fingers to bits. I love the original King Kong film and the ground breaking technology that came with it but compare the detail of Kong with the Natural History Museum Whale made at roughly the same time; which is better? See >>>

The whale was built to compliment the skeleton but it does far more than that for me. It brings the distant ocean within our weak imaginations. Two thirds of our planet is covered by sea water and it is a world we barely know and yet it provides most of our oxygen and, one way or another, most of our food. The colossal blue whale, all that size which was duplicated time and again in great schools of whales, is produced almost entirely from krill, another almost unknown animal which appears to be integral, along with whales, to the management of the very algal blooms that give us breath.

The skeleton of a the blue whale, now known as hope, hangs in the main entrance to the Natural History Museum whare the diplodocus used to stand. It is more than an antique. Stranded on a sandbar off County Wexford in 1891, she is solid proof that blue whales are natural visitors, or even residents of the British Isles. >>>

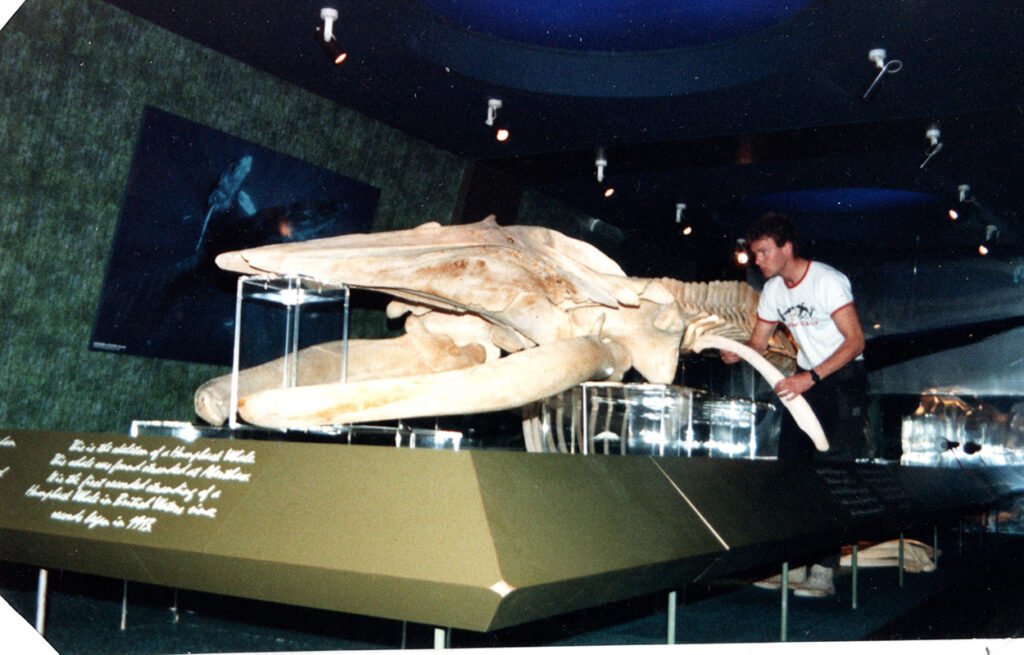

Humpback

My third museum boss, or bosses really, there were two of them, had been involved with a whale stranding just a couple of years before I arrived there. When something exciting washes up, the Museum, or zoology dept at least, drop everything and scurries out to make the most of it. Such was the case when a humpback whale washed ashore in south Wales. Humpback whales are rare in British waters after their virtual extermination by ‘whalers.’

One of my bosses, a taxidermist by title, could not abide the smell of rotting flesh! He was an expert model-maker, and taxidermy restorer and had no problem with fresh specimens but ripe meat was his Achilles heal. The other boss tolerated ripe meat perhaps a little too much and would go in slashing, sloshing and slicing without really thinking things through and only too eager to be eating a sandwich and so needed the other boss to rein him in a bit.

He and I went out into the wilds of Wales to meet with coastguards and collect the remains of dolphins found on remote beaches including white beaked and white sided dolphins. The discoverers rarely knew what they had found so we had to go out to all calls just to make sure. He was fun to be with. None of our trips were to giant whales though. I walked into the office one day to hear him on the phone as follows.

“Are you sure it’s a cetacean?”

“A dolphin or porpoise and not a seal.”

“What makes you certain?”

Ah, flukes, tail flukes, yeah that pretty much confirms it so…”

“Ah, that’s unfortunate. Pretty far gone then. I have to inform you that, by law, it is crown property and it is an offence for you to attempt to do that. You should know that as a coastguard and, if you hadn’t done it, the tail wouldn’t have come off.”

“No, no, no,.. You’ll be alright. You are allowed to move it up the shore if you think the tide might take it away for example.”

“It was, was it? You’ll be alright then. That’s a fluke, ha-ha. Well, I know where you are, we’ll be there in about an hour and a half. Cheers.”

He puts the phone down and then.

“Ian, keep your coat on, we’re off to the Gower! You have to keep these officials on their toes.”

The cast iron stomach (don’t read this if you don’t have one)

I don’t have a cast iron stomach and am probably as repulsed by rotting flesh as anyone else. I use tricks. The first is to only breath through my mouth (I find this helps prevent motion sickness too) primarily to keep the aroma out of my nostrils. The second trick is psychological and simply this… This will be over soon and you can wash it of, then you’ll have a specimen or a tale to tell, it’s worthwhile. It’s simple but it gets me through. I can be caught out if taken by surprise.

A kettle stomached colleague once came back from a two week holiday with a dead polecat that he’d found on the first day. He wanted me to prepare the skull (it had died because a car ran over its head!) and had wrapped it in several plastic bags. The ‘specimen’ was no longer handleable in the normal sense of the word. I opened the last bag and found myself pouring the contents out and I was away.

My most memorable experiences of the kettle stomach with a dead hippo and a little girl, though not together. I was working with a team to post mortem a hippo. Four of us were holding the heavy carcass open when the vet, working beneath our faces, and without warning, slid a scalpel across its stomach which immediately collapsed from its plumpish appearance with an ominous hiss. We watched in horror as a primarily green broth began to ooze out just as the warm cloud of gas hit us. I managed to hold on, using my trick, but two of our colleagues lost their grip on the carcass and commenced with uncontrolled retching.

The loss of their muscle power caused the weight open carcass to pull us remaining folk forward as it tried to close, our feet slipping and sliding as we attempted to stop it chomping down on the vet whose head was inside it, like a set of giant jaws. At just that moment, my latest boss came in and began trying to ask me if I had remembered I was booked in to teach a class of kids that afternoon. He was a self-confessed kettle stomach but valiantly kept trying to ask the question while I tried to assure him that I knew what he was trying to ask without breathing through my nose and trying to keep my footing. It was no good, he rushed out to join the retching party.

Anyway, back to the humpback.

In all the excitement of collecting a humpback whale, someone, somehow forgot or lost the flippers. It was a flipping-heck slap of the palm to the forehead moment for sure. For any other whale this is not such a big deal but the humpback has famously big flippers. Its scientific name is Megaptera… big wings. Part of my job was to reassemble the skeleton for exhibition and impressive as it was, it had to make do with polystyrene flippers to replace its lost ‘wings’.

This was a gory few days made fascinating and beautiful, if you like a good skeleton. That’s the magic of museums. If you find yourself in Cardiff, why not drop into the National Museum of Wales. You won’t be disappointed.

Love your local taxidermist

If your skin is crawling at the thought of taxidermy and the thought that museums are ghostly places full of dead things, I say give taxidermists and museums a chance.

- Taxidermy is an art in which only the surface material of the animal is usually retained. The internal body of the animal is carefully measured so it can be replicated. In a way, taxidermy is the reverse of butchery in that the skin is retained and everything else discarded.

- Taxidermy is not just the display of glassy eyed animals in glass cases. It can be used to show school children the intricacies of natural habitats in a setting where they can discuss it together and specimens can be used for handling so that visually impaired people can meet animals in a way that is otherwise impossible.

- Charles Darwin was a taxidermist, as was Edward Wilson who died with Scott in the Antarctic

- Museums are not just display rooms where people can gawp at the curiosities, they are arks of biological material including DNA and the bones , feathers fur and scales of species now excruciatingly rare or extinct and within their walls gather the expertise so important to understanding our natural world and how to preserve it . In the book Living in the Anthropocene, which contains about 40 essays summarising our effect on the planet and future hopes of survival alongside life on Earth, no few than 9 of the 38 authors are museum workers including the 2 editors who drove the publication.

- Museums contain within them, the history of scientific exploration. The BMNH for instance contains, among many others, the artefacts collected, noted, recorded and catalogued by the expeditions of Hans Sloane, James Cook, Scott of the Antarctic and Charles Darwin’s voyage on the HMS Beagle.

- Museums and museum work are grand affairs with diverse pedigrees, some bad in origin but always with something to show and teach us that is real rather than electronically fabricated from data-bytes. Museumcraft is every bit as skilled and impressive as stagecraft, its charismatic sibling.

Meanwhile, back on the beach

So… there I was at Ynyslas, with this big dead whale and a bit of a history with dead things large and small plus a secret longing to take it home somehow. Whale strandings are historical events.

This particular whale washed up on Christmas Day. It was a youngster at about 7 metres long but I never took the trouble to check its sex. It might have been tricky with the position it was in but in the event, the sheer size was impressive enough and the chilly wind hurried us along. We didn’t hear about it until Boxing Day night but it would have made little difference to get there earlier. Of course, it was none of my business. I’m not a museum taxidermist anymore. As far as cetaceans are concerned I’m just a civilian… Civil-Ian.

Even if I worked for local government, marine mammal and turtle carcasses are protected by regional and international laws and, to touch the ‘specimen’ I would need an appropriate wildlife licence (collection of marine mammals for scientific purposes) and would need permission from the Marine Management Organisation (a sub-department of DEFRA) and the Cetacean Strandings Investigations Programme (CSIP) who should be notified of such strandings. (See here >>>)

But there it lay, with its own list of unique features…

- At 10 metres long or less, Minke Whales are the second smallest of the filter feeding whales (only the rare pygmy right whale of southern oceans is smaller at just 6.5 metres)

- Minkes are the species most seen on Britain’s coast.

- Minkes, also known as little pike whales

- They can leap completely clear of the water if they want to but rarely do.

- Most Minkes in northern seas including British waters have a distinctive white band on the flippers and the head appears more pointed than other species leading to its common (‘piked’) and scientific names.

- They are shorter and chunkier than other rorquals but this isn’t immediately obvious in the sea. There may be pale crescent like markings behind the head and front flippers, almost as if it is pretending to be a shark with gill slits but again these can be tricky to spot .

- Many whales can be identified by the blow pattern from the blow hole as they surface. Minkes start to breath out about half a metre below the surface which results in a low and almost invisible plume rarely reach more than 2 metres high. A white splurge of bubbles under the water just before the whale emerges is a notable characteristic of how minkes blow. The dorsal fin appears simultaneously with the blow.

- The tailstock (the muscular area between the dorsal fin and the flukes) tends to arch high out of the water as they dive but without the tail flukes coming out of the water.

- Occasional curiosity about boats helps set minkes apart from other European rorquals but it comes with risks. Though normally shy, minkes are sometimes inquisitive and approach boats. They are very vulnerable to collisions with powered boats so laws exist to control the speed and behaviour of boat owners.

- Minke has become the most used name in recent years but Lyall Watson argues for a return to the use of piked (pointed) whale as more descriptive. Minke comes from the Norwegian name ‘minkehval’ which supposedly refers to a sailor called Minkie who used to shout “hval” whenever he saw anything in the sea, leading to undersized, or worthless, whales being called Minkie’s hval. This last bit came from Wikipedia but they cite J.G. Millais as the source. Another common name for them is the least rorqual.

- Minkie’s worthless whale may have had good fortune in being worthless to whalers. As the greater whales were driven to near extinction it seems to be Minkes who have benefited and filled the ecological gap from the advantage of an already worldwide distribution. This is partly why they are the whale we are most likely to see from the shore or from coastal boats. Being small they also can afford to come into shallower waters.

- Nevertheless, Minkes are now the World’s most hunted whale species and have suffered unexplained regional population crashes and strandings, was our whale part of a pattern?

- It is thought that Minkes can live for about 50 years

Is the law an ass?

All these laws may seem a bit much but we are losing these species. The seal act has helped made both grey and common seals much more accessible to people than they once were so I believe that protection, even if it doesn’t work in the end, is the best first precaution. From the coastal path, we see people flouting the law all the time. Often they seem to knowingly get out of sight of the harbourmaster and then hit the throttle. A moment of pleasure for a boater can be agony or death for rare marine life which, of course, gets all the rarer meaning less harmful people never get to see it. I’m not sure that the meek will inherit the earth; I think we need to fight and in the case of threatened species, laws help.

Even if I owned or ran a museum, I might have struggled to fit even this diminutive minke whale into it as a skeleton. It was terribly decomposed and not the best advertisement for beautiful cetaceans or marine life, but it just happened to have arrived in the worst possible state. For marine life in general, it would probably have been better if the whale had continued to float at sea as a food source. That is, of course unless it was toxic or carrying information that might help conservationists conserve more species. In the end, it was treated as a public health risk, bundled up and taken away. Some people loved it and took selfies with it, others were horrified that it remained on the strandline so long.

Living on The Strand

I’m a big fan of the enriched strandline. That band of marine compost around our coast, if left in peace, is the home of sand hoppers, prey of the rare beachcomber beetle and seaweed flies, insects with rare adaptations to marine life which are an important food source for gulls, rock pipits and bats among many others. Left to rest in peace, the whale would have skeletonised withing a few weeks and would have been on public display in a natural position, perhaps for a century or more under the proper care of the nature reserve wardens.

I wish this could happen with all large whale strandings. Many get stored behind the scenes in museums or buried for a future retrieval that might never happen, whilst millions go to museum to visit the ones that are on display. But if they can be skeletonized where they lie (or nearby and brought back), millions more could see them (without a trip to the big city) and be reminded of the wonders and treasures of the deep. This could be extremely important for those kids whose parent or teachers don’t do such a good job of engaging them with wildlife.

Not all museums need to be indoors and one thing wildlife enthusiasts need (however much we might deny it), is for more people to be enthusiastic about wildlife, so they don’t discard or destroy it as useless to humanity. How could we do it on the strandline without creating a right royal stink (some may ask)? My solution would be to bury in sand where it lies for about a year. It may need a little technical work to make it strong and safe when it re-emerges but what an attraction!

So how could we use this whale that we couldn’t keep?

Well, I have used it. I’ve written about it. We were profoundly moved by seeing it on the beach, even though we are used to things like that. So we included it, reconstructed of course, among our repertoire of illustrations, swimming free. As usual the point of this is to get the animal and its message out on view. In homes and out on the street, so people talk about whales, the oceans, the strandline and nature in general. I strongly believe that the best hope for maintaining biodiversity for tomorrow is to talk talk talk about nature. And act act act, when we can.

If all this has left you wondering how to sex a whale…

Sexing whales and dolphins is easy in theory, but not always quite so straight forward in practice! And darned near impossible if they’re laid on their belly on a beach weighing more than an elephant, decomposing and prohibited from touching without a licence. Have I made it sound difficult. If the above obstacles are overcome…

- Flip your cetacean over or, if it’s alive get it to show you its belly

- Look for apertures – especially slots that are along the central body line

- In females, the genital aperture is very close to the anal aperture and a long way from the navel. The genital aperture is the one at the front and the anal one is just behind it but closer to the tail. Alongside the genital aperture, parallel to it on either side are the mammary apertures in which the nipples reside.

- In males the genital aperture is closer to the navel and not a neighbour of the anal aperture. He may also have mammary apertures but if not, it’s a boy!

Female baleen whales tend to be larger than males of the same age. Whilst in toothed whales and dolphins, the opposite is more likely, but this is not a useful field guide. Only in sperm whales, pilot whales and killer whales are the males significantly larger than females. In mature bull killer whales the dorsal fin becomes tall and triangular rather than the typical hook shape of other cetaceans. Hopefully this means you won’t have to turn him over! In narwhal, mature females tend to have smaller or, more likely, absent tusks.

Lacépède and the pleated whale

Standing and looking at the body of the minke whale I felt a connection to Lacépède (1856 to 25) whose name follows the minke’s scientific name: Balaenoptera acutorostrata (Lacépède). Born Bernard La Cépède, he was a naturalist and musician who assisted George Louis Leclerc (better known as Comte de Buffon) in cataloguing the collection of the royal museum for King Louis XV in the great work: Histoire Naturelle – an attempt to catalogue the whole of life. It is within these 44 volumes that the famous picture of a giant octopus appears, dragging a ship to its doom. Both men were pre-Darwinian intellectual adventurers into the possibility (or reality) that humans are animals and that some kind of evolution is taking place over a much longer timescale than the bible suggested.

Bernard identified the differences between right whales (plus grey whales) and other filter feeding whales which he called rorquals after the Norwegian name ‘rorhval’, the pleated whale, which suddenly makes them seem cute, regardless of size, with their 60 to 70 pleats running from chin to belly button. The minke whale and the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) are both pleated whales in the family Balaenopteridae (meaning whales with wings) along with Sei, fin and Bryde’s whales (B. borealis, B. physalus & B. edeni respectively). The other pleated whale, the humpback, has distinctly larger wings than the other Balaenopterids and so is called Megaptera Novaeangliae (New England big-wing). The pleats allow massive expansion of the mouth so that huge volumes of water can be taken in and the squeezed through the baleen plates to leave behind a mouthful of food.

Lost Whale

Incidentally, the Atlantic grey whale (Eschrictius robustus), the lone species in the family Eschrichtidae, was probably extinct by the time Bernard was born. It is now considered a Pacific species but once thrived in the Atlantic too. Extinction isn’t just a loss but a sort of alienation. The Scottish Wildcat is a well-known icon for UK threatened species and rightly so as it clings to existence. But, there was once an English wildcat and a Welsh wildcat now rarely mentioned and once all three were one… The British Wildcat. Famous humans are often gone but not forgotten, resident species are not always even that lucky… just ‘Gone’.

And the right whales

We’ll meet Bernard again on the beach, but I just wanted to say that the remaining non-pleated whales mentioned above are just 3 in number and are the right whales: (Family Balaenidae), so-called because they were the ‘right’ whales to hunt. They include the great right whale Balaena glacialis, the bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus (meaning moustached sea-monster) and the pygmy right whale who is about half the size of her 15 metre long cousins.

Bernard on the beach

Bernard found himself on a beach near Cherbourg in 1791 with a young minke whale carcass just like the one at Ynyslas. His description of it, noting the sharp shape of the head, resulted in his name for it being published: Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède 1804 in Histoire des cétacées. Somehow, the ongoing production of Histoire Naturelle had survived the death of the king who commissioned it, the execution of his successor, the death of the Comte de Buffon, its originator and the infamous Reign of Terror in France.

Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, Comte de Lacépède: his own words on whales

Bernard probably had a particular fascination for all things cetacean. Here are some quotes from Histoire des cétacées as translated by Jacques Yves Cousteau and Yves Paccalet in their book ‘Whales’

Curiosity gets the better of us; we draw near to learn what we can. They live in the midst of the sea, like fish; yet they breathe like land species. They dwell in cold-water regions; yet they are warm-bloooded and quick to react to the world around them… They are huge; yet they can move about at great speed, even though they have only forelimbs and no feet as such… Of all the animals , none holds sway over so vast a dominion; their watery realm extends from the surface to the bottommost depths of the sea.

Whales are capable of showing an easy-going affection, be it between individuals within a herd, male and female, or a female and her suckling, on which she lavishes the tenderest of care, rears with concern, protects with solicitude, and defends with courage. This behaviour , which stems from keen sensitivity, sustains, nurtures, and motivates her young. Instinct-the inevitable product of experience and sense perception-is developed, broadened, and refined. The two of them get used to being together and sharing danger, pleasure and fear. This bonds mothers to offspring, females to males, and whales in a group to one another. No doubt this elevated animal instinct to a higher level and somehow transformed it into intelligent behaviour.

Bernard even imagined them as seen from outer space 20 years before Jules Verne was born!

Let our imagination transport us high above our planet. Earth spins below us; only the vast oceans that gird the continents and islands seem to be alive. From our lofty vantage point, the living creatures that dwell on the dry surface of the globe are no longer visible; we can no longer make out rhinoceroses or elephants or crocodiles or huge snakes. But on the surface of the seas we can still see large herds of animals swiftly plying measureless expanses of water, cavorting with mountainous, storm-tossed waves. These creatures – which from our imaginary perch in space we might well think the only living things on earth – are the cetaceans.

He foresaw what they would face before powered vessels and exploding harpoons…

Enticed by the riches that would come from vanquishing the whales, man disturbed the peace of their vast wilderness, violated their haven, wiped out all those unable to steal away to the inaccessible wasteland of icy polar seas…

And so, the giant of giants fell prey to his weaponry. Since man shall never change, only when they cease to exist shall these enormous species cease to be the victims of his self interest. They flee before him, but it is no use; man’s resourcefulness transports him to the ends of the earth. Death is their only refuge now.

There will be nothing left of this giant species but a few vestiges. Its remains shall turn to dust and shall be scattered to the winds. It will live only in human memory and in paintings. Everything on our planet wastes away and dies out. What drastic change shall give it a new lease of life? Nature is deathless, but only in aggregate. Man artfully contrives to beautify and revive some of her works; but there are so many others he damages, disfigures, and destroys.

These words and the pictures we drew to share on T-shirts, notebooks and wall art, are our homage to that fallen nomad of the sea.