We really are conservationists

Every product we send out is accompanied by a card thanking the buyer for supporting ‘our conservation projects’. What does this mean? Can artists, fashion brands or stationary suppliers actually help threatened species, or is it ‘Greenwash’?

A lot of businesses offset their damage to Earth’s environment by supporting charities, planting trees etc. Some clean up their act in order to retain or gain green consumers as customers. We’ve come into this shop-front world from the other side. As conservationists who’ve become product suppliers. Here’s a brief review of our hands-on conservation work.

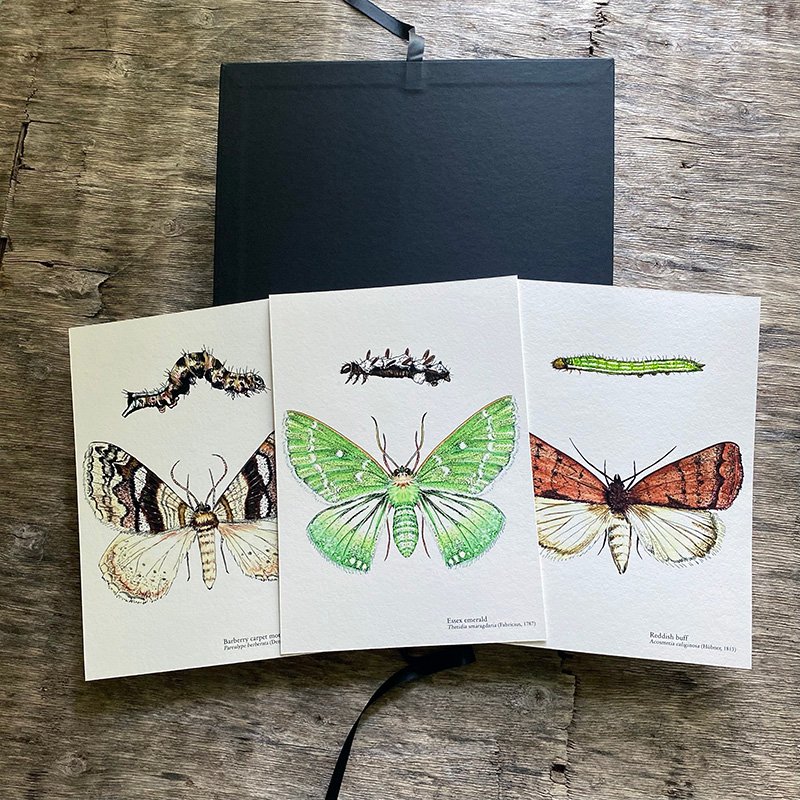

Barberry carpet moth Pareulype berberata

The Barberry Carpet Moth is not just one of Britain’s rarest and most endangered moths. It is one of the rarest lepidopterans. It was with the first to be ’protected’ under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act in 1981. I grew up thinking that ‘protected’ meant a species had been under threat and was now in protective custody and on the mend. It does not mean that. It hopes for recovery, but by no means confirms that it will or can happen.

Anyone hearing the name for the first time might think this is a species from the Mediterranean, ’Barbary’ region that eats carpets! This does not help the moth. In fact, Barberry (Berberis vulgaris), also called the pipperidge bush, is its foodplant and ‘carpet’ refers to the pattern on its wings.

For a long time the barberry carpet moth, having once been widespread, was restricted to a single known population in a Suffolk hedgerow (later destroyed by fire). A few other populations had remained undiscovered that are now known. But they still represent a very few dots on the map. Barberry is a much rarer plant than it once was, having been grubbed out of hedgerows as a host for a wheat-rust fungus. Wheat strains are now immune and/or sprayed against. There is guidance available on this. Barberry leaves and berries are edible and tasty and bumblebees love its flowers.

How the barberry carpet moth lives

Barberry carpet moths overwinter as chrysalises in the leaflitter around their food plant wrapped in a little silk sleeping bag they’ve built. We’ve found that they can survive frost or damp but struggle when the two combine. We’ve also found that the moths emerge at the same time that barberry flowers open (at least here in Wales). So if you see the lovely yellow Berberis vulgaris flowers, it is likely that the moths are active.

The emergent moths breed and lay their tiny yellow eggs on the underside of barberry leaves. A couple of weeks later, the minuscule caterpillars hatch and nibble characteristic little windows in the leaves, by scouring the underside but not going all the way through. By mid- summer they pupate and emerge as moths again, in the same year, to repeat the cycle. Their caterpillar babies hunker down for the winter as chrysalises (pupae) just as the sausage shaped berries of the barberry bush ripen.

Our work with the barberry carpet moth

We’ve worked with the Forestry England, BIAZA, Butterfly Conservation and many others to conserve the moth. We’ve done this by breeding it in cages to better understand its needs and introduce it to newly prepared sites. Also by growing thousands of food plants, which have been dispersed all over the country for major planting schemes. These include Back from the Brink and Highgrove House, who both joined the project in the last few years.

Most of the plants in the planting scheme originate, one way or another from us and the Cholderton Estate in Wiltshire along with a few other generous seed providers. In 2009 we initiated and launched the Barberry Highways Project. This project attempted to link zoos, gardens and other land owners together by planting barberry shrubs 50 to 100 metres apart along canal tow paths, roads, railways and other routes to give the moth stepping stones from one population to another.

For this project, and the ones that follow, our funding was short-term, always uncertain and began to involve different bodies competing with each other for the same funding. That can’t be right. Every species deserves its funding and full attention. So we turned our back on grant applications and looked for other ways to fund our work.

The work continues

We continue to grow barberry here in Wales for conservation planting. The larvae also eat the leaves of Berberis thumbergii and B.ottawensis which are commonly sold in garden centres and used in urban planting.

We’ve also worked, and in some cases continue to work, with gorgeous great crested newts, spectacular native crayfish, living fossil’s: tadpole shrimps and fairy shrimps, stunning fen raft spiders, very distinguished distinguished jumping spiders, Kerry spotted slugs, the fairest slugs of all, hazel pot beetles (who hide in lidded pots they build from their own poo), tansy beetles; the jewels of York, amazing medicinal leeches, medical miracles, not so muddy mud snails and others. But today they’ll have to wait. We have three projects that we’re particularly deeply involved with.

We now come to our three main conservation projects

We’re the first conservation breeders of these beauties

The Ladybird Spider (Eresus sandaliatus)

Eresus sandaliatus was thought to be extinct in Britain, but was rediscovered in 1980 by Dr. Peter Merrett (who coined the name ‘ladybird spider’ but prefers not to use it) on a patch of heathland about the size of a tennis court.

How ladybird spiders live and die

These spiders are sedentary and live in a burrow in one spot. More like a plant than a spider with juveniles usually dispersing less than a metre from their Mum. Normally furry and velvety black, the spiders live alone beneath a ‘tent’ of silk, which they decorate with the remains of their prey (mostly ants and beetles).

In his final moult, at 3 to 5 years old, the male emerges in resplendent colours very similar to a ladybird. He leaves his burrow to find a mature female about 4 or 5 years old. The male mates a few times before dying of exhaustion. The female will have just one brood of about 50 to 80 eggs. These hatch in her care in a silken nursery chamber she’s created. For a time, she feeds the spiderlings with fluids from her mouth, ‘spider-milk’, before dying. The babes then construct silk tubes within their nursery web, also their mother’s tomb. They work together to catch prey but otherwise live alone in their individual tubes.

Eventually the tube is extended away from the mausoleum and a burrow is excavated or the ousted spiderling finds a new home or perishes and the cycle begins again. This short-range dispersal results in little villages or campsites of silk tents. It also means Eresus needs help to leap-frog the forestry plantations, farmland, roads and urban sprawl that have fragmented what was once a vast heathland wilderness.

Our work for the ladybird spider

In 2000, working with Peter Merrett, Natural England and Forestry England, we, Lifeforms, were asked to “begin translocating spiders somehow” to new locations. Using my best attempts at innovation, I developed a technique for moving spiders which involves building them a little garden. In the last 22 years, we have conducted 19 translocations under licence from Natural England and we’ve trained reserve wardens how to do it, resulting in a 20th translocation by Dorset Wildlife Trust. This year will be the 21st translocation.

Not all attempts have worked, but we reckon about 13 populations are either stable or increasing. 6 introduced populations have been strong enough to provide more spiders for release. The method has developed from introducing spiders into wooden corrals, through settling them in urine sample bottles so they could build a web first, to overwintering them in specially made containers with a little garden for them to pitch their tent. The trick is to fool the spiders that they are free whilst not allowing them to run off so they have first class webs, a full tummy and a good community around them.

Autumnwatch

The appearance of the Ladybird Spider on Autumnwatch can be seen here >>>. It shows more about the habitat, the spider and the conservation project.

Helping us to help them

You can help us help the ladybird spider – By purchasing our T-shirts, books or other products, you are directly helping this species survive. We are currently creating new ladybird spider products, that we’re very excited to share with you. More on that very soon.

We are not a charity, but what we don’t spend on household bills and chocolate ice-cream goes to these conservation projects. There is help with funding from some landowners too, but it doesn’t cover everything and we have funded much of the work ourselves. We put out an appeal last year for hot chocolate containers – you can read more here>>>

Heathland and the ladybird spider will benefit from you becoming a member of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and, if you want to get more into spiders, why not check out or even join the British Arachnological Society.

Ladybird spiders in the news and our work honoured

This species has attracted more attention than any other species we’ve worked with. They have featured on The One Show (with Miranda Krestovnikov who helped introduce a successful population). Autumnwatch (with Gillian Burke who helped collect spiders for translocation) see above.

We were blessed with a visit by Chris Packham, before he took over as host of Springwatch, filming for a local Dorset programme. Our latest exposure, this spring, is to be on CBBC’s Deadly Predators. Presenter Steve Backshall, back in October, was crawling around on his hands and knees in our garden.

Caught in motion

In my teens I bought an amazing book called Caught in Motion by Stephen Dalton. I was entranced by the pictures and the technology, but especially the waxy gleam he had captured in invertebrates. Imagine my excitement when the author contacted me about ladybird spiders for his new book… Spiders, the Ultimate Predators. In much the same way that Eresus shelters beneath a silken canopy, Dalton took refuge from the sun beneath his silver photographic umbrella. He wrote about it in his book, which is among the best for promoting the positive qualities of spiders. Our ladybird spider male appeared on the back cover.

Last year, I was privileged to be made a member of the IUCN Species Survival Commission for, as they put it…

“in recognition of your outstanding contribution to spider conservation, in particular your role in the study, preservation and overall reduction of the extinction risk of ladybird spiders.”

Recognition from the IUCN… I’m happy with that!

Raising Awareness

All this attention helps raise awareness of the species, spiders in general and the broad range of action that is both needed and possible across the great diversity of lifeforms; but it costs in time and resources and does not bring us any money so, effectively weakens our work.

What helps is understanding individuals, whether they are rangers or administrators of reserves or people who buy from us. Both help us help ladybird spiders and help us give time towards public engagement, so millions of people can share the pleasure of seeing the ladybird spider on TV. I mention the IUCN above because they ask us to. I tried to turn down their offer as I did not feel I could commit to a commission, but they want to help and on projects they see as exemplary and they want us to ‘wave their flag’ to raise awareness for conservation across the diversity of life.

British Wildlife Journal

If you are particularly interested in species conservation, as opposed to wider environmental concerns such as climate change, the IUCN website is worth keeping tabs on.

For a less international flavour, British Wildlife journal keeps me up to date. To be honest, I don’t like depressing stuff and prefer to be out there doing things rather than hearing about how bad it is. So my strongest suggestion is to follow your interests and do everything you actually can for those families of species you care about, rather than bogging yourself down too regularly with news of biodiversity collapse.

For many people that does mean lobbying or standing between habitat and bulldozer and that’s fine but try to stay happy, you’ll be more productive and more effective that way. I know, if I’m feeling down, my work slows down.

Scarlet Malachite Beetle Malachius aeneus

A 1cm long, red and metallic green flying beetle once widespread in Britain, that visits flowers and grass heads in mid-summer. This beautiful beetle has suffered a decline to just a handful of sites during the 20th century and continued to decline in the 21st. The flowers it visits are common, so its decline isn’t linked to a loss of food plants. A Species Recovery Programme was launched for the Scarlet Malachite beetle in 1999. Sadly it foundered as English Nature was buffeted by government decisions and was downsized to become Natural England.

Our work with scarlet malachite beetles – its life cycle revealed

Twelve years later the populations had shrunk further and nobody was any closer to understanding the beetle’s needs. The situation seemed hopeless. The invertebrate conservation charity Buglife, asked if we could captive breed the beetles. We had no knowledge of their life cycle, so we needed to study them first.

To cut a long story short, we discovered, through building our own mini thatched houses, that the beetle’s larvae grow up in thatch. They migrate to meadows to court and breed, with the females returning to thatch to breed. We are the first people to successfully breed and observe this species as far as we know. The lack of untreated thatch close enough to low intensity meadows is a large part of their decline. We continue to monitor and conserve this species. Its known surviving populations are mainly in Hampshire and Essex, so it stretches our resources to the limit in the short summer season available.

The beetle was once found here in Wales but appears to have been extinct for about a century. Funding quickly evaporated for this project, despite the success. In 2016 we were granted Natural England innovation funding to build more of our cottages in the New Forest. Restoring this beetle to even small parts of its former range is a long-term affair. It is best seen as a flagship for restoring village greens as wildflower havens for butterflies and bees and young naturalists.

How you can help the scarlet malachite beetle.

Once again, buying our products enables us to help landowners with their small beetle populations and to build more cottages to establish new populations. The scarlet malachite beetle has no legal protection for itself or its habitat. We have not got round to it yet, but lobbying Essex and Hampshire County Councils and their wildlife trusts as well as those counties who have lost their beetles, to help us to help them would go a long way towards saving this species. Gentle reminders by third parties, that unpaid work is going on against all odds, go a long way I think.

Every little helps

The only way the beetle will return to Devon or Kent or Yorkshire, is if the people of Essex and Hampshire conserve it successfully. People often don’t or can’t see a way to help threatened species. They worry that it will cost the earth. But if we can afford to do it (only just, I’ll admit that) then surely a community of council, schools, museums, scout groups, home and farm owners and wildlife trusts and other groups could band together to save this pretty beetle and have fun at the same time.

If you want to create habitat (bearing in mind it does not travel far), its favourite food plants are meadow foxtail and cock’s foot grasses which are probably essential to its survival. Simply letting meadows and lawns grow and cutting only after mid-July would go a long way to restoring the old English (and Welsh) countryside the scarlet malachite beetle once knew. It would help many more species too. More info here >>>

In 2017 I was awarded honorary life membership of Buglife to acknowledge…

“the voluntary work and passion that you have contributed to the conservation of rare and threatened invertebrates in the UK… Recognising the work you have done on the ladybird spider, scarlet malachite beetle…” [and others].

Buglife sent word of our success to the Springwatch team who were keen for Martin Hughes-Games to come out and help build one of our cottages. Unfortunately, the risk of exposing the location of the beetles to too many people was too worrying on sites with no form of security so we had to turn it down. But there is hope that we can make this beetle common enough to be shared.

The Glutinous Snail Myxas glutinosa

The Glutinous snail is, predictably I suppose, the last to arrive in this blog! Europe’s rarest freshwater snail measuring up to 15mm carries a very thin, and unique, bubble-like shell which is usually partially or entirely covered by a retractable membrane of soft tissue. This gossamer-thin shell requires little calcium to build it and allows the glutinous snail to live in calcium poor water bodies, where other snails might struggle. Its Achilles heel is that it can’t survive long if a water body dries up. It seems to be particularly sensitive to pollution, agricultural chemicals and disturbance as well as efficient land drainage.

In Britain and the UK, Myxas (as we tend to call it) is restricted to a single known Welsh site. A site which also serves as a public amenity and receives run-off from surrounding roads, conurbations and farmland. Nothing was known of the snail’s lifecycle. It was simply clear that it was once widespread in Britain and Europe and has now disappeared from most of its range. Myxas is extinct, it seems, in 3 EU countries. In 2013 we were asked by Freshwater Habitats Trust if we could try breeding this species. They had a one year EU grant to be paid through Natural Resources Wales. We had already flagged-up Myxas as a species we thought we could help so were keen to get started. Once again, nothing was known about it and we had to work with and study very carefully this endangered and protected species.

Our work with the glutinous snail

Cutting a long story short again, by November 2014 we’d collected 6 snails under licence and placed them in a specially (though hurriedly) prepared tank. A year later they were breeding like the clappers and were ready to move outdoors.

They are now doing very well in our outdoor ‘ponds’ made from old oil tanks. Last year we had visitors from the National Museum of Wales visit to photograph them for a new Field Studies Council guide to Freshwater Snails. Additionally, for long-term comparative study, in 2016, we created some special refuges from both concrete and wood. These, being hollow underneath, allowed us to survey the snails in the wild without fear of crushing them when the refuge is lowered back down. We often have to snorkel down to them to check them! The refuges have also proved popular with bullheads and the critically endangered European eel.

Working with the rangers of the Snowdonia National Park Authority we were able to gain a much better understanding of how Myxas lives and what it needs. Permanent, clean water bodies that are warmed by the summer sun and have some feature which provides algae for the snail to graze on.

We’re ready to try introductions now. I think, with a little TLC to start them off, glutinous snails could live almost anywhere from giant reservoirs to ornamental ponds in the grounds of stately homes.

The bigger picture for conservation

There’s hope for all our projects, if people keep buying our products. But really, trying to save single species like these, so perilously close to extinction, is a bit like trying to save a puppy on an iceberg by throwing it a hot water bottle. They need sustained help and they are going to face new threats as the colossal juggernaut of human destruction will take decades or more to slow down.

That’s the other reason why we started Lifeforms Art… it’s for the bigger picture. Politicians tend to serve people who want material things: better roads, bigger airports, more buses, lower taxes, free insulation, street lights; you know the sort of thing. Naturalists, the real ones, don’t really want these things and the world’s wildlife is the same. The authorities have an insufficient remit and budget for wildlife conservation. They often have insufficient knowledge, experience, inventiveness or willpower to back up their meagre budgets. If governments and public bodies can’t save species and their habitats then it’s up to us ordinary folk; and we really can make a difference.

You can make a difference

To do it we have to…

- Act for wildlife on our own land and through communicating the need and the way to others. The way of the conservationist/naturalist is, on the whole, a lot cheaper and easier than mowing lawns, digging flowerbeds or paving driveways and patios and frequently jet-washing them.

- The most important long-term goal, in my opinion, should be to provide the support for children to become naturalists. Pre-school age is when it seems to happen (often unpredictably, sometimes unnoticed.) We should support and encourage youngsters where we can. They are the future for all species. Obviously that support should continue later but early exposure is the key. This is as much in the hands of parents, grand parents, aunts, uncles, siblings and family friends.

At the moment, many many people, even grown up people, have lost touch with nature. So much so, that they don’t know how to get back to it. We’re trying, every day of every week of the year, to show people the way. We think the best way is to display and talk about nature, nature conservation and its alter-ego or evil twin: extinction.

It’s simple really. The first action is as simple as letting grass grow or establishing a nettle patch (but of course the potential is endless.) The second is by sharing a picture that starts a conversation. On our walls, our stationary or on our clothes, we exhibit conservation starters and talk about nature in a positive way… what can we do , together, to enjoy the riches of life on Earth?

References and book recommendations

Information about the species we work with is pretty hard to come by. In truth, most people are only looking for information about such ‘obscure’ species because people like us have raised their profile. There are many more species (invertebrate or otherwise) that remain obscure, even in our own buildings and gardens or in the fields, woods and verges of our parishes and counties and many of them need help they may never get. The saddest fate for anything, I think, is to disappear without being noticed.

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways, William Wordsworth

The titles below are what I feel are the best to get you, or people you know, enthused and involved with invertebrates and their study and conservation at home. Identification can be made nightmarishly complicated and often involves expensive and difficult to read keys. Keys work for some people but, in my opinion, they are not the best place to start and more and more information is available on line or through local recording centres and wildlife groups. Joining groups is of course one of the best ways to learn and get involved and that’s relatively easy if you are comfortable with people. My advice tends to be aimed at the introvert who wants to help wildlife but does not relish the challenge of jumping into social situations. If you find yourself, humming Wanderin’ Star and just want the quiet life, hopefully the following will help.

Lepidoptera

Conserving the Barberry Carpet Moth by Paul Waring; British Wildlife Volume 11, Number 3, February 2000

I worked with Paul on barberry carpet moth conservation (and other projects) for many years. Paul provides news and views on a regular basis in British Wildlife journal. It’s also well worth looking at the Butterfly Conservation website (https://butterfly-conservation.org) before committing to buying the books below.

Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland by Waring, Townsend and Lewington.

Moths are more important and more colourful than we tend to give them credit for. They feed birds and bats, shrews and hedgehogs, lizards and toads. A great start to conservation is to plant the food plants of your favourite moths and see what turns up. Hanging a whiteish sheet from a washing line and pointing a light at it is fun to do and is sure to bring in all sorts of interesting insects.

Of moths and men by Juliet Hooper.

If you want to become absorbed in moth mania this might be the book for you. When support for Darwinian ‘theory’ was up against the ropes, it was moths who came to the rescue. This is one of the biggest and most intriguing stories in natural science. It’s primarily about the peppered moth but don’t let that put you off.

The Butterfly Isles by Patrick Barkham

Sets an example of a way to get back to nature. I don’t suggest a mad twitching spree but following Barkham around through his words, chatting about butterflies, brings back a lovely simplicity to enjoying nature and I have to admit, though not a twitcher, he does make me fancy seeking out the 60 British butterflies.

The Butterfly Gardener by Miriam Rothschild.

This may be tricky to find now but beautifully hands on about the pure enjoyment of gardening for lepidoptera.

Spiders

We often have to be brave, either to face spiders or to talk about them to those who don’t like them. I believe that arachnophobes and arachnophiles can live in harmony with the spiders themselves with a little understanding.

My own publication efforts are:

The Ladybird Spider Rearing Project by P. Wisniewski and I. Hughes, International Zoo Yearbook Volume 36, 1997

The Ladybird Spider in Britain its history, ecology and conservation by Ian Hughes, Roger Key et al. British Wildlife Volume 20 Number 3 February 2009.

I much prefer books to computer screens so Spiders, Learning to love them by Lynne Kelly is one way in but the British Arachnological Society website (https://britishspiders.org.uk) or membership is probably the best way to keep fully informed and up to date.

World of Spiders by WS Bristowe

Is in the old New Naturalist series and tricky to buy and a bit pricey when available but Bristowe was a spider watcher and lover rather than just a recorder or data processing biologist and, although some of the names have changed, this is a beautiful book. He does full justice to the ladybird spider, known then as Eresus niger.

Spiders, The Ultimate Predators by Stephen Dalton

What can I say? Don’t be put off by the title. I feature in this book so I love it but I often refer to it because Dalton really sees the beauty in spiders, he places British spiders as important amongst a global ensemble and collects for us, some prize snippets of spider lore and photographic tips.

On the Margins, The fen raft spiders of Redgrave and Lopham Fen by Helen Smith and Sheila Tilmouth.

We’ve helped with this project and I get a flattering mention in this one too but the point is that it’s a cracking book about spider appreciation bringing spiders and art and natural landscape beauty together with conservation and science. It’s everything Edward O. Wilson would want from our involvement with nature.

Britain’s Spiders by Bee, Oxford and Smith.

The Wildguide series are comprehensive ‘bibles’ to get you involved with British wildlife. If you only buy one book on spiders and want to meet them and know them, buy this one.

Heathlands

As heathland is the home of the ladybird spider and it is only by preserving, conserving and enhancing heathlands that the spiders will survive it’s worth knowing how precious it is. Vastly depleted heathlands need our help. There are 4 books called ‘Heathlands’ that I know of. One is a lovely introduction in the Discover Dorset series by Lesley Haskins, another is in the old Collins Wild habitats series by Chris Packham, beautifully, informatively and enthusiastically written with a nice mention for Eresus.

The remaining two are larger tomes; one by Nigel Webb is in the old New Naturalist series and the other is bang up to date by Clive Chatters; Number 9 in the British Wildlife Collection. If you buy one book, buy Clive’s. If you are interested in the intricacies of heathland management, the RSPB have produced ‘A Practical Guide to the Restoration and Management of Lowland Heathland’ which is pleasant to read and useful too.

Beetles

The most up to date information on scarlet malachite beetle ecology and conservation in the UK is on our website or on the way to our website if we haven’t typed it up yet. Like moths, beetles can provide endless fun and study for naturalists and artists alike.

Beetles by Richard Jones.

Don’t buy this book if you are looking for information scarlet malachite beetles (there’s hardly anything) but do buy it if you want a gentle but passionate introduction to the world of beetles.

Coleopterist’s Handbook by Jonathon Cooter

Same comments as for ‘Beetles’ above. Its more scientific than Jones’s book but focused more on British species and on beetle handling so the two work nicely together.

Britain’s Insects by Paul Brock

This may give you all you need without buying the above two books if all you want to do is know more about the various insects you see or want to see or know about. Paul discovered at least two of the known scarlet malachite beetle populations almost doubling the known range. Sadly, this wildguide does not feature the scarlet malachite beetle but it is a very useful book for budding entomologists none the less.

Meadows are the habitat of scarlet malachite beetles. If you want to know more about them then George Peterken’s ‘Meadows’ is Number 2 in the British Wildlife Collection and very informative and eye-opening. There’s also interesting information on meadows, heathland and most other UK ‘habitats’ in Oliver Rackham’s History of the Countryside.

Snails

There’s not much information available on glutinous snails. Our website is probably the best start. Water snails don’t get much attention either. I recommend the following.

Freshwater Snails of Britain and Ireland by Rowson, Powell et al.

This is a Field Studies Council publication in the AIDGAP group.

Atlas of the land and Freshwater Molluscs of Britain and Ireland by Michael Kerney

The conchological Society website (https://conchsoc.org) is worth a visit as of course, is the website of Freshwater Habitats Trust (https://freshwaterhabitats.org.uk) who produce a book, The Pond Book, which is full of useful information that will help you help pond snails and other freshwater life.

I’ve never dug a proper pond. I dig a hole, line it with cardboard or newspapers so no stones poke through and then cover it with builder’s damp proof membrane. This method has never let me down. It’s cheap, easy and recyclable but lasts for decades or more as long as you don’t puncture it. Obviously the proper way is better if you have the resources. It’s worth creating flat shallow steps as well as deeper cooler areas rather than just a steep sided ‘fish-pond’.