A Study in Scarlet

Introduction – Breakthroughs

We had some breakthroughs in 2021 and 22. Slowly but surely through managing and monitoring our little scarlet malachite beetle nursery cottages, we accumulated enough confidence to have another go at captive breeding, really just to find out what the larvae (beetle grubs) eat. Are they specialists on bees or some unusual species whose decline or rarity has caused a crash for our beetle? Or are their needs fairly simple and simply not met by how we humans run the countryside these days.

Last year we finally bred some beetles. We had larvae; a break through, we saw them feed; a breakthrough and we raised them to adulthood… they broke-through! It’s a modest success but, enough to make us twist and shout, if it’s not to early for a Beatle pun, and we now know that a block of thatch without any special treatment or prey species or other food, will support a population of beetle larvae through to adulthood. We’ve already had success managing their adult habitat, meadows. So, having been working 8 days a week and giving them all my loving, I now feel confident to tentatively write, the account below.

Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth

Arthur Conan Doyle

Introductions – The Beetles

Despite the hysterical millions of fans who’ve flocked to see, hear and pay the magically musical stars, The Beatles, change just one letter, to Beetles and the ‘fannage’ depletes to a microcosm by comparison. It wasn’t always like this, the Egyptians deified the scarab which they envisaged rolling the sun across the sky like the all important dung balls so important to crops in the Nile delta. I’ve seen it said that the mumification and entombment in mounds, of important people was an attempt to replicate the dung beetle life cycle, seeking metamorphosis to a more wing-ed afterlife with the mummy being the pupal stage. I like that.

I am inordinately fond of quoting, the inordinately quoted geneticist and wit J.B.S. Haldane who himself was inordinately fond of saying that what we know about God is that he, or she, must be, or have been…

“inordinately fond of stars and beetles.”

Maybe Haldane meant Ringo Starr and the Beatles? Beetles are probably the most diverse group of animals, or living things on Earth (nematodes are apparently still in the running but beetles are the hot favourites) despite the fact that they only occupy the one third that is land (& freshwater) and face the same limitations as all terrestrial life which reduces diversity in polar and desert regions. Nevertheless, the world has an estimated one to three million species of which nearly half a million have been named and classified into 175 families. In the British Isles, 102 of those families can be found, represented by over 4000 species. This makes our 90 odd mammals (about 50 of which are bats or marine mammals) look quite pathetic by comparison even when added to our (roughly) 200 resident and visiting birds and (roughly) 60 butterflies. Even the mighty Beatles’ (roughly) 13 albums are a paltry number, though I’ll shy away from counting their fans; I’ll let it be.

So yes… if there is or was a creator, he or she was or is, seemingly, inordinately fond of beetles or they got inordinately out of control a bit like us. And if ‘God’ is Mother Nature, then Beetles… She loves you, yeah, yeah teah.

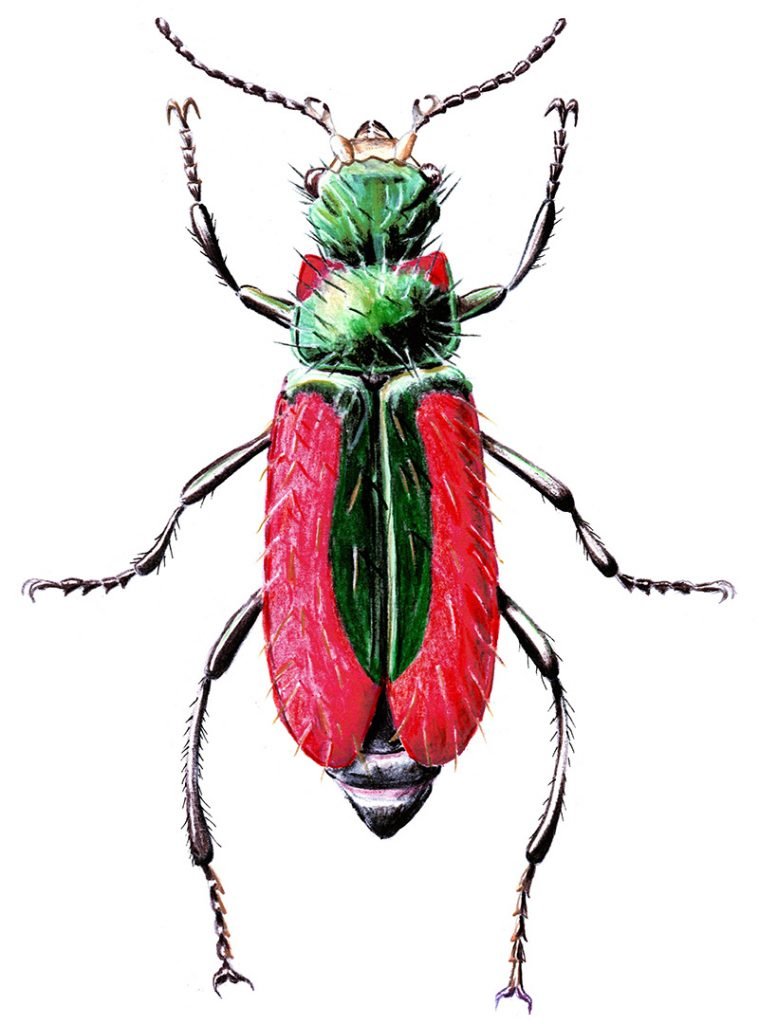

Malachite Beetles

Among these many beetle families (a magical mystery tour, it must be said) sit the Melyridae or soft winged flower beetles with 26 British species some of which are metallic green and have become called Malachite beetles (Malachius). The brightest and reddest of these little living gems is the scarlet malachite beetle, once a common sight in the British countryside (especially the south) but now perilously close to extinction and placed on the Species Recovery Programme list in the 1990s. On sunny days in late spring and early summer they fly from flower to flower where they busily munch away at pollen or interact like mad March hares.

Malachius Aeneus

The scarlet malachite beetle’s scientific name is Malachius aeneus. To make this document a little more readable, I use the scientific name and the abbreviations M.aeneus and SMB intermittently but they all refer to the same species. If you look at this species online you will find, as I have, a confusion of records, remarks and reports. Some are about work unknown to me and seem mostly uncorroborated or out of date. I know of no living scarlet malachite beetle populations outside of Essex, Hampshire and (possibly) Surrey, which total up to 7 very localised populations. Only 3 of these describable as strong or stable and at least one of the other 4 thought to be extinct. Our experience with the scarlet malachite beetle has been simply to figure out what it needs to survive, by working with the beetle, in captivity and in the wild. We have looked at a lot of sites and talked to a lot of people but the research is far from comprehensive. If you know of other scarlet malachite beetle sites and can send us pictures and descriptions (which might save us a long trip and a lot of time) we would love to hear from you. This is the story of what we’ve found and is intended to be about beetles and not people or places but they are, in many instances, interwoven.

Anonimity

Without saying too little I have tried to maintain the anonymity of sites and site owners where possible and appropriate. I am very grateful to these people but fear that exposure of locations could lead to unwanted, and unsustainable, attention for beetles and land owners alike. If you wish to follow this beetle for professional or other conservation reasons you can contact me or go through official channels to the appropriate government body (e.g. Natural England).

In the Beginning – HELP, I need somebody

When I was younger, so much younger than today, I was barely aware of this beautiful little beetle, and had never heard its common name, until 1999 when I was asked to offer suggestions for its conservation by Dr. Roger Key who was project officer for the Species Recovery Programme (SRP) initiated by English Nature who were the government conservation agency now known as Natural England. Shortly afterwards I was given a female Malachius aeneus by another Species Recovery Programme worker.

The beetle was a female and appeared to be fat and trying to oviposit (lay eggs) but no larvae were seen in the container. She lived for about 5 days. My suggestions to the SRP were not followed up (nobody had the time or money it seems) and I was struggling to gain interest from potential breeders in the Zoo Federation because it was so specialised a project with nothing known of its lifecycle.

About seven years later I received an email from Coleopterist Mark Telfer reiterating the request for expressions of interest from zoos to breed the species. Frustratingly, I had no resources to become involved independently at the time and my colleagues in the Zoo Association (BIAZA) were still not in a position to help at that time either although it had been on a list of species-pending since 1999. I cannot criticise zoos for this. They have limited resources and the odds of making this a workable conservation project, were stacked against it with the risk of watching beetles die without breeding, troublingly high.

Buglife

It is much easier to gain the assistance of other breeders if you can provide a reliable breeding protocol which shows it has been done before. But if you can do that, you no longer need the breeders! In 2011, Vicky Kindemba of Buglife contacted me, with a potential contract to attempt to breed the beetle. The contract was short-term and meagre. I was probably being foolish taking it on but I agreed. The information regarding this species was incomplete and seemed to be contradictory and woolly. Among the observations that kept re-emerging was that the beetles always seem to be near thatched buildings. Forgive me if I am wrong but this seems to have come from the wife of the Essex entomologist Mike Rowley. Sadly, I have never met this astute lady, not do I know her name but the suggestion was already there in 2000 (discussed at the SRP meeting in a slightly bemused manner) and wouldn’t go away.

Presumed Extinct

The scarlet malachite beetle (Malachius aeneus) was formerly widespread over southern England and Wales (and there are scattered northern records extending into Scotland) but declined through the 20th century until, by 1999 it was presumed extinct in Wales and known from only a handful of sites in England. Of the remaining known sites, only three: one in Hampshire and two in Essex seem to be relatively strong with other populations weak or extinct in Hampshire and Essex. Our limited searches (following up on negative surveys before us) have failed to find M. aeneus at other historical UK locations.

Experiments

Through a series of experiments, we discovered that scarlet malachite beetle larvae grow-up primarily in the roofs of thatched buildings although we have records from other buildings (adjacent to a thatched building and a courtship meadow), potentially from log-piles or wood-stores. Prior to our experiments, M.aeneus was known only as a beetle that visits flowers in flower rich hay meadows (almost exclusively known from adult beetles) with the following notable exceptions.

- A 1999 report to the Species Recovery Programme by consultant entomologist Peter Hodge noted that the Victorian entomologist Canon William Weekes Fowler (from whom most early historic records originate) seems to have considered M. aeneus to be a woodland species. I have little to go on with this and can only say that the surviving population shows no obvious preference for woodland habitats and that the opposite seems more true. Whether something else is now lacking from woodland or environmental changes have forced M.aeneus out into more open habitat I do not know.

- Peter Hodge’s report records a beetle larva found in a log pile in Devon which was reared by its discoverer and emerged from its pupa as a scarlet malachite beetle. Looking at the information, the site was near one of England’s largest reed beds and it is possible that the woodpile itself was thatched but we will probably never know for sure.

- Online sources from North America, where M.aeneus was introduced in the 1800s and is widespread, record a larva found indoors in a house drawer which was reared to become an adult scarlet malachite beetle. I have not been able to contact the discoverer so far but I am told that there is no thatch in the area and conclude that perhaps the roofs are wood-tiles or shingle or the building contained some other suitable substrate for M. aeneus to develop in.

- Our main study site (a hay meadow) was owned by the discoverer of the beetles (who has since sold the property) whose house was not thatched and never has been although it is thought to have been built in Tudor times. However, each spring scarlet malachite beetles were found indoors (upstairs) usually just (a few days) before beetles began appearing in the meadow. As windows and doors were shut and the beetles seem to be attracted to light and were alone on the owners windowsill in one room only, we concluded that they were emerging in the building. Examining the loft I found a light leak (a hole) through a shower fitting into the room where the beetles are found. It seems highly likely that these few beetles (one or two annually) were emerging in the loft and attracted into the house by the light leak which was locally stronger than others to the outside. The owner then had a malachius larva drop into her book as she was reading in bed at night. I could confirm from her photograph that it was malachius but we never confirmed it to be M. aeneus. We concluded that, by its behaviour it did wanna be a paperback writer. Whether M. aeneus or not, this congenator proved that malachius larvae were in the house and could survive. We guess it came through the overhead light fitting. I searched and vacuumed the loft (yes, I’m a sucker for beetles) but found only a single Malachius pupa which emerged as the slightly smaller species Anthocomus rufus which is known from buildings. Two large wasp nests were present in the loft. Perhaps these provide enough food to sustain a few beetle larvae?

Beetlemania

Our main study site, like most historical scarlet malachite beetle sites, supported a small population which congregated in a small area whilst surrounded by suitable plants. When disturbed the beetles fly away or in circles and are difficult to follow. When watched without much movement the females are largely sedentary with the males moving from female to female courting but females do sometimes move as well and new beetles seem to arrive while others leaves but again, their movements are tricky to follow without a capture-mark-recapture experiment. We felt interference would upset land owners and potentially harm and disturb beetles and habitat.

Emergence Traps

We set up emergence traps on the small patches of meadow where the beetles are found and have taken soil, root and stem samples from the area and the surroundings. We also set up flight path traps and netted portions of the large thatched building nearby in the hope we might find beetles delayed as the attempted to move from thatch to meadow. None of these yielded any larvae or pupae but the only substrate we could not search thoroughly was the thatch. We asked the owners of the thatched buildings to keep all windows and doors closed (just as their neighbour, the population’s discoverer was doing) until the first beetles of the season had emerged and we once again found that some of the earliest beetles appeared indoors in upstairs rooms.

Scarlett Malachite Beetle Heroes

This incredibly important and useful information was gained thanks to the earnest endeavours of two schoolgirls – SMB heroes! We released beetles into netted enclosures and found that they could locate the tiniest gaps and escape in seconds. This indicated that our nets (terylene) pinned to thatch and our flight traps would be ineffective. The emergence traps in the meadow were made of transparent and highly reflective netting which had no gaps so we were confident that any beetles emerging in the nets would stay in the nets. Gradually over a few days, beetle numbers built up around the nets but none were found inside.

On a day when beetles appeared to be joining the throng we returned to the thatch and found at least two individuals landing on a lawn immediately adjacent and partly overhung by the roofing. These appeared to be newly emerged beetles (though we cannot know for sure) and they quickly took flight and disappeared in the direction of the meadow about 50 metres away. It seemed highly likely, with all elements considered, that the beetles were emerging from the thatch and courting in the meadows. Unfortunately the thatch was too dense and too expensive for us to search any more than we had. Vacuuming lofts around the country showed that, if they are living in thatch, they are primarily in the outer layers whilst searches of the outer surface suggested that, if they were in thatch, they were somewhere beneath! But, as Conan Doyle’s creation Sherlock Holmes would put it… we’d eliminated the impossible, so whatever remained, no matter how improbable, must be the truth… and as far as I could see, only the thatch remained.

Beetles in bondage

With land owner agreement I took some beetles away for captive breeding trials. Without going into detail the results were not very encouraging. Some beetles were kept in moth breeding nets and others in an aviary with as many suitable plants as we could gather and more plants (flowers) offered daily. We observed them feeding on flowers, eating other insects and, apparently ovipositing but if they were producing eggs they were too small to see. However, we had some success when a male beetle emerged in our aviary the following year. The substrate provided was layers of hay and straw on top of a variety of logs. It was not thatch and the modest result gave me a glimmer of hope that I might solve the riddle.

The building of the Ark

In spring 2014, while the beetles were active, with every crumb of knowledge accumulated, Ben and I built two nurseries in the field which the beetles seemed to cross between hay meadow and thatch. It was an arable field (usually wheat) but we had seen beetles courting on the wheat and the farmer had kindly pledged to leave the beetle corner unmanaged so suitable plants could grow there. Our nurseries were roughly thatched frames containing hay, straw and logs and made as shrew-proof and bird-proof as I could manage using 5mm weld-mesh. The nurseries, which we started to call nursery cottages whilst the farmer called them ‘hives’ were made to be deconstructed so we could search through them for any beetle larvae that may be within. As we were building them, beetles were landing on them, it seemed like a good omen.

Pink Larvae

Opening the cottages the following April we found little pink larvae which looked a lot like the online photographs from America. It is with some delight that I can say that the new owner of the meadow was the first to spot a larva in our sorting tray, another SMB hero! Moments like this are very special and obscure beetles can be a tricky thing to get people enthusiastic about but we were away! I took a larva away and it promptly pupated. A fortnight later the pupa darkened and became more starkly patterned and then, to our delight, a scarlet malachite beetle emerged. Although we’d learnt a lot about Malachius aeneus over the preceding couple of years, it was the larvae in the cottages and this one beetle that finally gave us the beautiful dawn of hope feeling. Unfortunately, the Buglife Officer, Vicky, already struggling to raise even half the cost of the work, had left her post and the funding had reduced and dried up as the work gathered pace.

Funding

With some ‘Innovation Funding’ from Natural England we (George, Jake, Ben and I), have since built more cottages in Hampshire as well as more in Essex part funded by Dudley Zoo and Acton Bryan College and the Essex Wildlife Trust topped up by ourselves, Beachcomber Jewellery and a private donor, June Rogers, and have continued to work with land owners to try to understand and enhance M.aeneus populations. Kerry sources materials for us and plans our accommodation, and sometimes comes along, so it is a real family affair. The other populations yield extra clues from the positions of their thatched building(s), their meadows, greens and verges and where beetles are recorded that allow us to steadily build up a picture of what scarlet malachite beetle paradise might look like. I cannot thank the land owners enough for their help support and understanding for something which could be a nuisance to them with a different frame of mind.

Flighty Beetle

As I said earlier, when we first started studying this beetle it was known as a flighty beetle that visited flowers in meadows in June and July. It was not known whether they were visiting flowers for pollen, nectar or to prey on other insects. In the second spring of our study the owner of our main study meadow came up trumps with a beetle who followed suit. With doors and windows closed, lovely Arlene, of larva in her reading book fame, found a beetle indoors on the first warm day of spring in late April. It still holds the record for the earliest emergence. Fortunately, I was already there (in Essex) as I wanted to be there when the emergence began, but was there very early (at crippling expense) to put emergence traps and other paraphernalia in place as well.

Unfortunately, our beetle had emerged so early that none of his known food plants were blooming yet. The only ‘flowers’ I could find was pussy willow and I placed some in his little pot. He immediately proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that scarlet malachite beetles eat pollen as he ravenously devoured the stuff and became visibly fatter to boot. Fearing that he’d flake out before a mate could emerge, I put him in the fridge until we saw more beetles. He was in the fridge for two more weeks before the meadow began to fill up. Scarlet malachite beetles do not give up their secrets that eagerly and we are not all that well resourced to conduct thorough and unambiguous scientific study, but here is what is emerging.

ATTRACTANTS

Plants

Anecdotal and survey observations consistently reported M. aeneus as a flower beetle and the reports, along with photographs seemed to suggest that almost any flower would do and that the beetles perhaps favoured buttercups, hogweeds and other umbellifers. The SRP information leaflet featured a scarlet malachite on a buttercup and it looked very much at home there. However, Peter Hodge and colleagues recorded observations which pointed to cocks-foot grass as being attractive and perhaps the most visited flower. It featured very strongly in their observations.

Grasses

When I first set foot on a scarlet malachite beetle site the association with grasses became immediately much clearer but cocks-foot had not yet begun to flower. On my very first visit to an SMB site, beetles were flying about a lot as it was a muggy day but most were head downwards on the flowerheads of meadow foxtail grass. A single beetle was found in one field (in the gateway where it met the other) and this was on a buttercup but with no flowering grasses close by. It seems that M. aeneus has a preference for grasses but will make-do with other flowers if grasses are absent or if all the grass heads are occupied. Once mated, females probably become less fussy and simultaneously more voracious whilst males are possibly happy with any pollen but are attracted to the females. It seems to be the plant structure that is important. Females take up a position, head downwards on a grass head which appears to be a mini-territory. However, cocksfoot is one of the few grasses visited by bees and both species are important fodder plants for livestock.

Arable Field

After looking at the meadow, we strayed into the arable field which lies partly between the meadow and the thatched roof and here we found another concentration of beetles but, with no meadow foxtail present, they were using wheat (another grass, and one used for thatching) in much the same way and it was here that I saw courtship behaviour for the first time. The wheat-field beetles were concentrated near a gap in a hedge which lay between them and the thatch and trailed off towards another hedge gap which led to the meadow.

The meadow beetles were concentrated near a gateway which led, via a driveway, to the thatch and also trailed off like comet tails in both directions along the field edge; one tail towards the wheat-field and the other towards the second meadow, where the lone beetle sat on a buttercup. We didn’t know at this stage if they were coming out of the soil, grass stems or the hedge or nearby trees but it looked for all the world, as if they were emerging from the thatch and following the simplest paths to suitable grasses, avoiding flying over or through hedges and preferring (or relying on) gaps and gateways. We set out to disprove this and could not. A few paces into each field and the beetles dwindled and then were absent, each one on a meadow foxtail head. I returned at night and they were roosting in the same places (some a little further down the stems) head downwards like bats. A lot may have changed in the scarlet malachite beetle’s world but my experience suggests to me that their emergence is synchronised with the environmental conditions that bring about the flowering of meadow foxtail. As the foxtail goes to seed they switch to cocks-foot grass for structure and other grasses as well including wheat and slender foxtail (or black grass) which is a wheatfield ‘pest’ but very attractive to our beetles.

Light

We rarely find scarlet malachite beetles in the shade and, if the shade of a tree moves onto them, they tend to move to a sunnier place. In some situations, such as field edges, they seem to be attracted to grasses (or other beetles) but then lose the sun as it crosses a high hedge. On these occasions the locations of beetles we’ve found suggests that the light of the meadow seen through the hedge has lured them to take the risk and go that way. I tested beetles in my hotel room and they flew to the strongest light whether it was the bedside bulb or the window. Similarly, when Ben sat in a large black terylene cage and released beetles from a container, he only had unzipped it by 1cm and the beetles could quickly find the way out. This apparent xylophobia does not sit well with the great Victorian coleopterist, William Weeks Fowler’s experiences, but it is possible that the beetles he was finding were in large glades (where populations) might have been contained or on woodland edges or that the climate and/or flora of the time made a difference. We may never know what Fowler knew but today, they seem to be strongly attracted to bright sunny meadows when they emerge and court.

Other scarlet malachite beetles

We cannot confirm 100% that fighting breaks out between females over flowerheads as territories. It all happens so quickly and it is difficult to confirm the sexes of new arrivals in the fray. But tustles do occur and they don’t always result in mating. In captivity females seem perfectly tolerant of each other and it is males who do all the pestering. On the very first visit, collecting beetles for breeding experiments, their seemingly sociable behaviour gave me enough confidence to put a few beetles together in one pot. My confidence disappeared in a puff however when, after 10 minutes together, we found a male completely dismembered by his travel companions. In close confinement, they must be considered as dangerous to each other with females especially, I thought, being potentially cannibalistic.

I have seen similar behaviour in fairy shrimps in confinement where the seemingly stronger and more aggressive males are dismembered when in close confinement with females although this may be when the male moults and is especially vulnerable. New information burst on the scene this week as we accomplished our first terrarium based breeding of SMBs – the first in the world as far as I’m aware.

An interesting development

The first male to emerge, to great celebration was quickly named Lucky Jim. Another male quickly followed, he was slightly bigger and so was given the name Hercules. Hercules was placed in the same tank with his brother and all seemed peaceful as they fed on cow parsley and ribwort plantain flowers. When I returned however, I could see Hercules, but was struggling to relocate Lucky Jim. Eventually, I glanced at the floor of their shared home and noticed the tiniest patch of red. I looked more closely. It was the thorax, well, half the thorax of a scarlet malachite beetle… Lucky Jim! Nearby was part of a wing cover and a leg. I felt like the police officer in Jaws who finds the remains of the first victim and Lucky Jim looked like the remains. I stared at the remains and, as I wondered if, perhaps, some other predator was in the flowers and had done the dastardly deed… Hercules landed on the floor with and audible thump (more of quiet click really but he’s one of the smallest beings ever to be called Hercules).

Not so Lucky Jim!

He approached what was left of Lucky Jim and pounced on it, picked it up and shook it like a dog with a chew-toy, dropped it and moved on. Hercules had killed and eaten his own brother but there was nothing I could do to induce him or the next male to emerge, to eat flies or other insects. They were only interested in pollen. So, it seems that inter-male aggression is pretty strong, at least in fairly close confinement.

DETERRENTS

Obstacles:

As stated previously, scarlet malachite beetles seem to emerge from their pupal casing and fly straight to the most convenient flowering grasses if they are available. However, hedges, buildings and/or shade are rarely crossed and the beetles are more likely to find a gateway, gap or low point where they can cross from one field to another or from garden, or track into suitable habitat. Whether this is an adaptation to avoid flying predators is unclear. It may be that crossing obstacles is ruled out in their ‘pre-programmed search for their breeding community which could have existed for thousands of years on grasslands grazed by large, now extinct, herbivores.

Courtship

Male scarlet malachite beetles have adaptations near the base of their antennae which look like C-shaped snap-on clips. Their normal function is to pick up ‘scents’ and airborne vibrations but the antennae appear to be used expressively by the beetles in much the same way that a dog uses its ears to the point that you can almost see them thinking!

Females feed on pollen primarily on grass heads (but sometimes other flowers) and wait, head downwards for males to arrive. The entire community are presumably attracted to each other by pheromones but the initial attractant which causes the congregation seems to be flowering grasses in a sunny location. Whatever the cause, the beetles appear in the same places year after year. Males land on the stems below the females and head up towards them. We have seen scuffles at this point presumably males falling out over the same female on her podium but we cannot yet properly confirm this.

Eventually a lone male reaches a female and nods his head as he approaches. She nods in response until eventually they head butt each other (we prefer ‘kiss’) and her antennae become caught in his C-clips as if they were a pair of rutting stags. They may be locked together for a few seconds. This kiss allows her to ‘taste’ a substance from a gland on his face and, presumably again, assess his suitability to mate. If acceptable, she turns her back end towards him and they mate. Mating, in my experience lasts only a few seconds to a couple of minutes, but in beetles…

Behaviour towards people

Approach a scarlet malachite beetle on a grass stem in warm weather and it is highly likely it will fly away. Approach slowly or in cooler weather and it may simple sidle out of view behind the grass head or plant stem. Conclusion, they identify us as potential predators and are nervous and flighty in response. On one occasion, late in the season, I was finding only females and happened to be wearing a red T-shirt. On two occasions females performed head bobbing displays as if I was a male beetle approaching. Whether this was the red of the T-shirt (like Tinbergen’s sticklebacks) or simply the movement, we have yet to discover. This recognition of our presence can make observation and captive management tricky when we are looking for ‘normal/natural’ behaviour.

Behaviour change

Once again, this has been difficult to properly confirm but mated females appear to change behaviour. Rather than congregating in the sunny meadow it seems that they begin looking for places to lay eggs. They seem to oviposit on almost any dry vegetation: wood, reeds, paper, grasses etc. but the eggs are so small and the beetles so shy that I have not positively identified one despite many hours scrutinizing the wet patches left behind. Yes I probably should be taken into protective custody and weaned off this obsessive behaviour. Wild beetles simply dwindle away but captive females may live for many weeks. They disappear for a few days at a time and then return to flowers to feed.

Lucky Jim’s slightly luckier mother, lived for 76 days in our terraria and we don’t know when she emerged. This is, admittedly an artificial situation, with substrates and flowers chosen by humans, but it is our best source of information at the present time. Occasional searches for missing females have resulted on two occasions, with females being found inside hollow stems of phragmites reeds. On other occasions they are just resting beneath the dry foliage. If this is correct, that they forsake the sunny meadow and search for dry vegetation, nooks and crannies to oviposit on, it marries up very well with the larvae emerging from thatch, since thatch is not exactly a meadow and is, however, close it may be, a separate location by definition. I think this also helps explain the Fowler anomaly. Maybe he was seeing females that were converting to egg laying or that the wood still had suitable elements. Peter Hodge speculates that woods are very different now and end abruptly whereas in Fowler’s day (late 1800s) there would be more merging of these ‘habitats’. I have another theory I’m toying with below.

Prey

Males have only been seen eating pollen (and brothers) but females sometimes become predatory and eat other insects (mostly flies). I have not seen one kill or pursue prey so they may only take dead or dying animals, but I have not seen a ‘prey’ item dead before hand either except when offered by me. Often, such offerings are refused so maybe particular nutritional needs are met, on demand, as appropriate and the primary diet is pollen.

Hearing?

Whilst conducting light experiments, a scarlet malachite beetle resting in a jar on a table responded to the bark of a dog outside! The door was closed and the dog was about 50 or more metres away barking repeatedly. Every time the dog barked, the beetle’s antennae moved from forward pointing to a backward pointing position and then back again. There is no doubt that it was in response to the dog, but whether it was felt by the whole body or just antennae is unknown. As I understand it the basal segment (at least) of the antenna, is equipped to detect airborne vibrations. There’s no reason I can think of, why bird fearing beetles shouldn’t hear or feel airborne vibrations but it was an interesting way to find out.

Egg-laying

I do not have magnification instruments powerful enough to confirm the presence of eggs, but we have seen some pretty convincing specks and smudges following the extension of the ovipositor. I make the assumption that a female is actually ovipositing when the ovipositor is extended and probed around on surfaces, but it is possibly that it is occasionally just flexing for some other reason.

On one occasion, in the wild, we saw (in a wild situation) a male common malachite courting a female scarlet malachite who, in response, extended her ovipositor. This year (2022) the emergence of the first female, who was placed in Hercules’s enclosure, began extending her ovivpositer and dabbing a pinkish fluid onto the cow parsley she was resting on. He responded with similar abdominal activity and what looked a lot like a fluid production too, but without the extendable apparatus. Perhaps it can be used to release pheromones to attract or dispel suitors? Often the ovipoisitor is used in a probing action with its tip disappearing in cracks and fissures in wood and grass stems. What the ovipositor tells me is that this beetle (as not all beetles have one) hides or delicately places it eggs. It seems to do this on primarily dry surfaces: wood or grass/reed stems. It is easily conceivable that M.aeneus oviposit on grasses in the courtship meadows as well as elsewhere, but that these fail to survive either through mowing, grazing, humidity/damp issues, predation or exposure.

If M.aeneus is vulnerable to any of these threats it help to further explain a modern-day apparent dependence on thatch as simply the part of their realm where larvae can survive. In an investigation for Buglife in 2006 and 7, the eminent coleopterist, Dr. Mark Telfer, dissected a female and examined the ovaries. He reported that she had…”81 ovarioles in one of her two ovaries, each containing an egg c.0.9mm long at an identical stage of development. Assuming that the ovaries were symmetrical, this female would have been capable of producing 162 eggs.” Dr. Telfer also said…”oviposition has never been observed in the scarlet malachite beetle, at least in the wild. To observe an ovipositing female would be a breakthrough in our understanding of the larval habitat of this beetle.” I can say with absolute certainty that I think I’ve seen it! Slightly more seriously, we can say we’ve seen oviposition style behaviour from a female who certainly produced viable eggs.

Life-cycle of the Scarlet Malachite Beetle

We have now observed the full Malachius aeneus lifecycle through a combination of habitat management and construction, observation of wild specimens and various forms of captive breeding and rearing. It goes as follows:

- Eggs – laid in June and July on various substrates hatch with about a month. Females produce over 100 eggs.

- Larvae – emerging the same summer or early autumn as they were laid overwinter primarily as larvae and pupate in the spring.

- Pupae – develop over a period of about a fortnight changing from pink to red-black piebald just before emergence.

- Adults – emerge from the substrate and fly to congregations of other M.aeneus or (in the absence of other beetle) to suitable locations where other beetles will congregate. Courtship and mating takes place on grass (and other) plant stems and leaves but with an apparent preference for meadow foxtail, black grass, wheat and cocksfoot for courtship. They eat (and probably need) large amounts of pollen which is sometimes supplanted by eating other insects.

The life cycle takes place over one year which means that breaks in the cycle can extinguish populations. For instance, beetles using one thatched roof or one meadow can be exterminated by a re-thatch, a fire or a mowing incident at the wrong time of year and these threats persist year after year.

Longevity

Two females have had particularly long lives among our captives. In 2012 a female captured on 1st June survived 49 days until 19th July. This is significant because the meadows were normally mown on 4th July. Last year (2021), the record was smashed by, Lucky Jim and Hercules’s Mum, a female collected on 31st May who survived in very active health until at least 12thAugust… 74 days minimum, but I’m often heard claiming 76 as she was pretty sprightly when last spotted; “Feeding on the flowers of meadowsweet”.

We couldn’t be sure until adult beetles emerged but were hopeful that this female, let’s call her Eve, produced our 20+ larvae. Whilst it is possible that 74 days is an extreme age, never attained by a scarlet malachite beetle in the wild (she’s only the 2nd SMB I’ve seen in the month of August and the other was also in captivity), it is equally possible that it is perfectly normal and that meadows, mown earlier and earlier, faster, neater and closer cropped, have being becoming ever more hostile for this beetle whose only chance is to court and breed earlier than it sometimes would. This could easily explain their extinction more than a dependence on thatch.

Site and population management

We have been very lucky that landowners and householders have been patient and highly co-operative. I have vacuumed lofts of thatched buildings in several locations in Essex and Hampshire, asked people to adapt their gardens, keep windows and doors shut on hot days and keep an eye open for tiny beetles which, if they see ‘em, watch carefully or even capture.

Our work in Hampshire was perhaps a little too late beginning and was a bit of a stretch with our own funding and we have had little measureable success there so far. At one population we found single beetles in 2 consecutive years, where once there were many. We erected our cottages in what I thought were key locations to benefit them and the landowners worked hard to cut hedges and tree branches to create flight paths from thatched buildings to the meadows where scarlet malachites were once plentiful. But to no avail; no M. aeneus have been seen since before our cottages went in about 4 years ago. The declines seem to follow the local re-thatching of roofs (perhaps critical south-facing elements of roof?).

In the last known Bedfordshire site M. aeneus apparently disappeared after the verge was mown more regularly and closely, followed by it being dug up to install some sort of conduit. But in the corner of an Essex field, our friendly farmer has assisted what feels like a little miracle.

Farmer Roberts Miracle

I showed Farmer Robert what I believed the beetles were doing… flying from the thatch through a gap in the hedge into his wheat field and then pausing a while if suitable plants were there or making their way to the next hedge gap, to the meadow where the largest congregations were found on meadow foxtail grass. They then had to make their way back to the thatch about 50 metres away. Although the beetles fly well, they are not as fast as the swallows which hurtle up and down the drive they have to cross or the wrens which live in the hedge they pass through.

I said it would help enormously if we could put ‘thatched’ structures in his field corner that we could search through for beetle larvae. He agreed without hesitation taking us forward in a single bound to a situation where we did find larvae. His neighbours who owned the meadow and discovered the beetles in the first place were selling their property and were worried that my structures (hitherto unseen) might put off potential buyers. Perfectly understandable and ultimately the new owners were very beetle friendly, but human needs can easily delay invertebrate conservation by a whole beetle generation.

Robert offered to widen the field boundary so the field edge could be more suitable for the beetles. “Just put in some markers so we know not to plough it,” he said. He was very generous with the corner he set aside and within a couple of years we had a nice little meadow there with lots of beetles. In a way the field corner success was a home goal because, quite happy where they are, fewer beetles are now going as far as the old meadow where we were trying to see if they would extend their range by using our cottages far far from the thatched building. It’s a problem I can live with as hopefully they will extend their range anyway.

Paradise for a Scarlet Malachite Beetle

So what does’ natural’ scarlet malachite beetle ‘habitat’ look like? What is missing in Britain that has made them decline. What does paradise look like for them? Of course I don’t know, I can never really know, but I’m trying to listen to what the beetles are quietly saying. They come from a time when there were no divisions between woodland, hay meadow, arable field or paddock; these were all one eco-system.

Pollen

The pollen record suggests (or even shouts) of a landscape covered with trees (some now rare species) with an almost completely closed canopy. Did many meadow-type animals live in meadow-type habitats above this canopy? Or were they absent from this area spreading as humans developed their (or our) control of the landscape? I don’t completely trust the pollen record. I’m no expert but I suspect that judging past landscapes by looking at the pollen record can, in places, be like trying to work out someone’s curriculum vitae by looking through their letter box.

Unlike volcanic ash, sand or waterborne sediments, pollen, in its active phase, is alive and much more diverse than minerals. Some plants produce masses of pollen for their size, others very little, some pollens are adapted to catch the wind, others prefer to wait for an insect taxi service, some pollens are highly palatable to insects others are ignored, some pollens are light, travel far and float, others are heavy, more sedentary and sink. Floating pollen on a waterbody is likely to travel through wind wave or ripple actions, to the edge where it might take luck to detect it. Pollen landing on ice could have a very different future if it is then covered by snow or dust before melting occurs. At the same time, winds can prevail or change as can the numbers and behaviour of animals and some land features can trap or miss catching pollen in much the way that dunes work with sand.

Trees

I think that over much of the British and north European landscape, the giant herbivores, now extinct kept many ‘trees’ in a ‘stunted’ condition at about the height of a typical grass sward. Occasionally, individual trees, or clusters of them would take advantage of reduced browsing and break away, gaining height to create a savannah like landscape. Among the trees would be mighty elms (meadow trees really rather than woodland species) renowned for dropping giant branches periodically and for their water resistant wood – a dry habitat for insect larvae. I suspect, or at least like to speculate, that the dense boreal forests, where they existed were largely or partly the result of mega-fauna extinctions as mammoth, elephant, rhino, hippo and giant deer populations collapsed in the apparent wake of human advance. Grasslands, whether natural or caused by humans were once more tussocky.

Large herbivores, people and carnivores follow favoured paths, skirt round fallen trees and other obstacles and, with otherwise complete freedom to roam, leave an uneven impression on the landscape. Scarlet malachite beetles, I believe, zoomed about amid a much richer animal and plant assemblage through a mosaic of tall and short grass dotted with trees. Meadow foxtail may always have been a favourite food source and courtship platform, but it may just be what they’re left with. I’m pretty sure though, that the structure of paradise comprised grasses and other plants very similar to meadow foxtail.

In his book, ‘Meadows‘, George Peterken describes meadow foxtail as a ‘floodplain’ species which inhabits other damp meadows. Whilst I have found it in such places, I think of it as occurring in sunny spots in meadows and roadside verges often well away from water. If it really is a wetland plant, how does this sit with our beetle whose larvae seems to need dry locations?

Nests

Across this landscape, birds’ nests, some on the ground and some in trees (and fallen branches) offered natural thatch as a larval nursery. Many of the larger native birds are gone or much depleted: storks, cranes, great bustards, would all have created fabulous thatch and herons, swans, ravens, buzzards, rooks, kites and eagles all once much more common than today would have added to such opportunities. At ground level and below, skylarks, ruffs, woodcocks, harvest mice, hedgehogs, dormice (even bears) and bumblebees utilising mouse and bird nests all provided potential dry ‘thatch’ for scarlet malachite beetle larvae. Around rivers, lakes and fens, after periodic floods, banks of reeds and other vegetation would pile up and could remain many years before the next significant flood which may only nudge the material to a higher place with most of its terrestrial invertebrates still living within, afloat for a day or two in their weedy ark.

Amongst all this, busy beavers, transform the landscape, felling trees to create sunny glades and thatching their dams and lodges (yes thatching) with reeds and grasses. Both birds nests and beaver lodges are dry and both would provide insect food (fleas, mites, ticks, fly larvae etc) for the Malachius larvae. Imagining this landscape now, it seems incomprehensible how comprehensively we have carved our world up into neat packages depleted of biodiversity and it is obvious what an easy life it once was, comparatively speaking, for the scarlet malachite beetle who just fitted in nicely to the glorious assemblage.

A mammoth idea!

There is another more radical possibility, a mammoth idea! The vast grasslands and tundra at the end of the last ice age were home to mammoths and woolly rhinoceros as well as other large herbivores who swapped places as ice came and retreated. Mammoths were like moving, living thatched buildings who could have provided metabolic warmth for scarlet malachite beetles as well as insect prey through their parasitic passengers. Dead mammoths could be as much use to Malachius as living ones although a live mammoth could transport a cargo of larvae further south to warmer conditions in winter and then back to the summer meadows at breeding time. Prehistoric people are known to have used mammoth bones (and surely skins) to construct huts and probably combined this with thatch so it is no great leap to place the two together as complimentary habitats with two (or more) species adapted to grasslands.

Simliarly, though perhaps less radically, mammoth and other mega-fauna dung would have been both thatch like and nest like, teaming with insects and generating heat as it decomposed. My Malachius breeding tanks could just as easily have been mammoth dung balls and I suspect the beetles would have survived just as well in there. So, for humans and none humans alike, paradise can be variable.

If you want to view paradise, simply look around and view it.

Want to change the world? There’s nothing to it.

Willy Wonka

Paradise lost

Whatever actually happened, and whatever scarlet malachite beetle paradise looked like, into this beautiful realm of butterflies and bees, humans began to build in number. Their nests were thatched and they created large grassy areas, grass heaps and log piles which added to the paradise. But they were changing the landscape and paradise was doomed. Recently, perhaps the last remnants of wilderness for them were the dense tussocks of dry grass that can accumulate around old cocksfoot grass plants; nests without need of a nest builder. These are now mown away or grazed or flattened. Perhaps it helps to view a scarlet malachite dystopia now to understand what paradise was like?

Manageable habitat

Whilst I now see scarlet malachite (manageable) habitat as an open (to uninterrupted sunlight) flower rich meadow, well stocked with pollen rich grasses including meadow foxtail, crested dogstail, cocksfoot and slender foxtail adjacent to dry, thatch or thatch like material which would suggest they favour or need a dry habitat, there are some anomalies which raise questions and surprising theories as retaliatory answers. The first and most obvious question is , what did SMBs breed in before thatch.

Hopefully I’ve covered that adequately but, if it was the hollow stems of reeds (let’s face it… before the days of wheat fields) then we are looking at a species much more associated with wetlands or wetland edges. We then have to face the fact that most people writing about what I consider to be SMBs favourite plant, meadow foxtail, describe it as a plant of wet areas and water meadows. Off on two other tangents, the only known larva in Britain prior to those we have found, came from a log pile – and not thatch – at Slapton Ley in Devon and one of the oldest and most prolific recorders of SMBs and British beetles generally, William Weeks Fowler, considered SMB to be a woodland or at least woodland edge species. So what’s going on here?

Reedbeds

Just as we’ve found with the ladybird spider Eresus sandaliatus, scarlet malachite beetle adults seem to avoid shade and the larvae avoid light, though they do both seem to like it hot and dry. Larvae spend most of their time (in captivity) inside the tubular straws of wheat or phragmites or in wheat seed heads or similar nooks and crannies. Interestingly, one of the males that recently emerged, ‘Lucky Jim’, in the absence of females, and possibly in response to a chill in the air, took up residence in a dry stem of Alexanders where he peeped out of the top. It now looks likely that he was hiding from Hercules and instead of photographing his cute antics, I should have been rescuing him. As I’ve said, having long wondered about ‘natural habitat’, I felt fairly sure, for a long time, that they were a dry grassland species but now I wonder. If Meadow foxtail is a plant of damp places, it may only be a stand-in for some lost species as far as SMBs are concerned, but they seem to be very attached to it.

The historical record from Slapton Lee and another large reedbed near Glastonbury urges a look at reedbeds and adjacent habitats and, in Hampshire we tended to see them on a flowering sedge (with no other flowering grasses nearby). So, I wonder if they were once more of a wetland species which needed dry patches provided by those heaps of dead reed, crane and swan nests, beaver lodges etc. As I’ve said, I think in many instances the heaps of reed which pile up at the top of flood plains and river banks are not as susceptible to further inundation as they might seem. In most cases the surface material probably gets lifted by rare higher flood waters and simply placed in a more elevated position making it safer and dryer still. REPEATED ABOVE It’s also possible that SMB larvae could survive in air pockets within the reeds and that is partly why they ‘like’ hollow reed so much.

Farmers would clear this detritus away (more so as farming became mechanised) but before farmers it probably was a significant feature of the landscape. Similarly, Fowler, considering the scarlet malachite beetle to be a woodland edge species throws up some questions. Peter Hodge was as gob-smacked as I am by this knowing what we know and speculated that woodland management had changed enough to make this difference. But I wonder if it was surviving in the clearings afforded by woodland ponds, free of shade and full of thatch + lots of birds nests. In such a situation it could also utilise deadwood as larval habitat as a reliable stable sunny courtship clearing was readily at hand in the shape of the reedy pond. Remember that, at Slapton Lea, an unidentified larva was found in a log-pile and reared to maturity, emerging as a scarlet malachite beetle. This led us heavily speculating about and experimenting with deadwood as a larval habitat but there was a large adjacent reedbed and I would not be at all surprised if the logpile was thatched. We’ll probably never know.

So… I think there’s some flexibility in where we try to establish scarlet malachite beetles as long as the appropriate food and courtship plants and structures are there, close to thatch-like material that is raised off the ground enough to avoid it becoming soggy. I certainly support the continued reinstatement of wetlands and, along with the reinstatement of meadows, place it higher in importance than the planting of trees.

Distopia

Let’s assume, conventionally, that scarlet malachite beetles arrived (late) with farming, and that grassland was as rare as the pollen record suggests from about 10,000 to 6000 years ago when grass pollen and grassland plants re-emerge in the record. As fields and commons were created and arable weeds and grasses became more common place, the woodlands of Britain shrank to make room and new assemblages of wildlife arose taking advantage of the new open areas and low level flowers.

We humans are grassy animals. We eat cereals and we eat animals that feed on cereal and grasses. Bread, milk, cheese, butter, eggs, beer, beef and wool all need grassland. Our main source of locomotion and heavy labour until recently, horses and oxen also needed grass to fuel them. Additionally, grasses and reeds were probably the most commonly used roofing materials and were not just used on housing but on churches, barns, gateways and walls. The world of living grass crops and meadows in combination with stored grasses and thatch was a virtual utopia for scarlet malachite beetles. But times would change.

The following are just a few of the more obvious problems Malachius aeneus has faced and faces today. Perhaps the earliest blow was the decrease in thatched buildings due to thatch’s combustibility and the convenience of tiles and slate. The tussocky nature of scythe mown meadows and crops, the amount of wilderness, commons and rough pasture and the cataclysmic drop in the already low population of Europe compared to today probably created circumstances well able to support M. aeneus but perhaps it felt a pinch in places.

Then came the Inclosure Act (Enclosure Act if you prefer) of the early 1800s and an intensification of farming. Patches and swathes of wild grassland disappeared and more hedges arose. I like hedges but for an animal that seems to avoid crossing them, the Inclosure Act was probably a bit of a bummer and led to populations being separated from each other or divided into smaller suitable areas. A blaze or two in a thatch, a barn or a meadow and the distance between populations increases. Crop diversity decreases and, as a consequence, hay meadows go into decline. Many M.aeneus populations (all the ones we know) are now out of touch with each other, some populations depend on a single thatched building or meadow and it is only a matter of time before some disaster strikes.

This is probably enough to put the scarlet malachite beetle in a localised state with populations dotted here and there with one population never close enough to replenish or re-instate another that has declined or disappeared.

But there is worse to come.

The railways carve the landscape up into smaller portions and farming intensifies further alongside open-cast mining and quarrying for road, rail and building materials. The internal combustion engine leads to a reduction in hay meadows, especially for city horses and farms change as export and import puts very different demands on the land and mechanised farming follows through. The last refuges for M. aenus are now village greens and a few low intensity meadows if, and only if, there is suitable larval habitat nearby.

The only remaining habitat that can support a self-sustaining population is thatch. The future seems bleak for scarlet malachite beetles at this stage but the onslaught is not over. The neat and tidy brigade mow the village greens for both amenity and aesthetic purposes. Road verges, another occasionally suitable refuge are impacted by increasing traffic, a loss of diversity in plants (which used to support the notoriously healthy ‘gypsy-horses’) and more mowing. Thatch, where it has survived is often pretty lonesome and beetles cannot survive in one roof while another is re-thatched or suffers a fire, shading or damp, they’re simply too far apart. Re-thatching is increasingly conducted using imported thatching materials with the old material left to go damp or burned. The replacement thatch is fumigated making it hostile to Malachius prey and toxic to the larvae themselves and here we are, extinction looms.

Today

Today’s farmers tend to follow a national code that makes use of every corner of every field and only respects fragments of threatened species habitats where they are discovered to exist rather than where they once existed. This is not enough for many species.

Today’s highway managers are all about safety, utility and flow of traffic and have no time or understanding for the cycles of myriad lives within road verges and hedges. This is not enough for Malachius.

Today’s community, councils and greens managers rarely understand the needs of diverse invertebrate communities and, even if they do, are under pressure to conform to what are now considered conventional amenity provisions such as mown lawns, play areas, benches, paving and trees.

Whilst I fully support no-mow May, it doesn’t help the wildlife communities whose worlds are strimmed and mown away in summer when most insects (including the more noticeable butterflies) are eggs or larvae, or the autumn and winter when they need refuges in which to hibernate. The well meaning chaps, so eager to hop onto a sit-on mower and devastate wildflower, insect, small mammal and low-nesting bird assemblages seem to abhor long grass for no other reason than that it clogs a mower… they’ve got a mower to ride, and they don’t care! This landscape-shaving approach does not suit a beetle whose last refuges include a few village greens.

Today’s gardeners or home-owners are, even in rural areas, much more urban-minded than ever before with paved or tarmac-ed parking areas and patios, decking, exotic planting (sometimes intensively managed) and lawns mown to less than a centimetre with no place for taller grasses or herbage. Some gardens are better than this but many are much worse. Few gardens suit the scarlet malachite beetle. Today’s thatch owners have very expensive roofs and very expensive insurance. They have the threat of fire, rot and infestation. Few thatch owners are thatchers themselves and have to trust expert advice in a society where everyone wants to make the largest amount of money for the least effort and outlay and where only competition from similar businesses keeps prices down. In turn, thatchers are expected to keep roofs healthy and allowing or encouraging insect communities within the thatch contrasts with what is expected of them. Thatch has no status as a habitat for Malachius aeneus even though it is effectively their last refuge. Like Noah, they need an Ark to get them through this catastrophe.

In his 2019 New Naturalist book Beetles, Richard Jones writes:

“The red and golden green scarlet malachite beetle, M aeneus, was once widespread in Britain, but for no very clear reason has declined to the point of near extinction in the last 50 years and is now the subject of concerned conservation surveys.”

Richard Jones

In 1999 expert coleopterist Peter Hodge writes in his consultancy report contracted by the government conservation agency, English Nature:

“100 years ago Malachius aeneus was apparently not a rare species, at least in the south of Britain, although even in the 19th century it was considered to be ‘local’ by some writers (e.g. Fowler, 1890). Its distribution covered almost the whole of England and also parts of Wales, but the only mention of the species in Scotland is that by Stephens (1839).

However, a dramatic decline has occurred in Britain during the 20th century and colonies are so localised that extinction may occur before the end of the 21st century if no action is taken.”

Peter Hodge

Peter was at a loss as to what the cause might be and what the larval habitat might be. No connection had yet been made with thatch and the only known larva had been found in a log pile. He speculates that Malacius larvae could survive in deadwood in hedges (I agree) but says that ‘ if this is the case, it is hard to understand why M. aeneus is so localised in Britain’. He speculates that M.aeneus decline could be due to ‘the decline of habitat mosaics of woodland edge and unimproved grassland. Most woodlands end abruptly with little or no edge habitat’. Again, I agree that this could be a contributory factor.

I can feel Peter’s frustration when he says… ‘ The latest Species Action Plan gives the reasons for the apparent decline in M. aeneus as ‘Unknown’ and this really sums up the current situation’.

I am very pleased to say that things have come a long way since then and there is hope for scarlet malachite beetles in Britain.

In the last 10 years we have:

- Found that, in the UK, scarlet malachite beetles prefer to court and feed on grass heads, primarily meadow foxtail, black grass, wheat and cocksfoot but also others. They will feed on other flowers, especially buttercups, cow parsley and oxeye daisy and sometimes breed on them but these appear to be less favourable and usually ignored if ripe flowering grasses are present.

- Seen larvae in the UK for the first time in living memory

- Through finding larvae in the first year of building our nurseries and rearing them to adulthood, established that scarlet malachite beetles have a one year life cycle. This increases their vulnerability because, at any one time, an entire local population may be in one place, for instance, their courtship meadow, or the nursery thatch. This helps explain why the species has become so rare and helps us plan to re-establish it.

- Confirmed that the larvae survive primarily in thatch and similar dry to slightly damp vegetation.

- Confirmed that males and females eat primarily pollen but females will also eat insects (perhaps when suitable pollen is scarce); Sometimes larger than themselves.

- Built bespoke structures (incorporating thatch) in which scarlet malachite beetle larvae developed

- Created new meadow habitat (based on observations) which became occupied by breeding scarlet malachite beetles

- Bred the beetles in a large aviary (admittedly we only found one beetle, a male, but it gave us hope.

- Maintained a gravid egg laying female under observation for 76 days

- Bred the beetles through their entire life-cycle in small vivaria

- Discovered larvae eating spider exuvia and insects meaning that, whilst they may have food preferences and dislikes, they are not specialised feeders and their primary needs are thatch like material for larval growth and meadow-like habitat for courtship and mating

- Discovered that at least 4 larvae can survive to adulthood in a loose ‘block of thatch’ 30x20x20cm which means that the much larger nursery cottages could sustain 30 or more beetles and so are viable conservation tools that could be placed on meadows where no thatched buildings exist

- Discovered that males will fight viciously with the victor eating the loser

- Discovered that males (in captivity) seem less fixed to meadow foxtail grass as a food and perching plant than females and seem to favour cow parsley and ribwort plantain.

This beetle can be saved if Britain wants to save it.

I call on councils, schools, scout groups, landowners, home-owners and conservation organisations to help create the habitat it needs. The scarlet malachite beetle is the Little Gem of Essex and the Jewel in the Crown of the New Forest and Hampshire, living heritage and a true resident of their traditional greens and meadows and beautiful thatched buildings. As far as we know, it is extinct everywhere else or very very rare.

The Ark

Our nursery cottages were designed and built to find out if scarlet malachite beetles were using thatch as a larval habitat simply because we could not explore the expensive and vulnerable thatched roofs. Thatch is expensive but our cottages are beetle arks as cheap to build, or cheaper, than a garden shed. Gardens are probably not the first great hope for this beetle but village greens (with more wildlife tolerance) and school grounds and other amenity areas almost certainly are.

I see places mown and paved seemingly for no other reason than to exclude long grass where nobody is ever seen to picnic or play ball. If school today is anything like my schools, at least half the kids in class have no interest in chasing balls around or competing with each other and would get much more out of turning at least one of those immense playing fields (which are empty most of the time) into a wildlife reserve. I know some schools have done this but all schools should if our children are going to understand the natural world and our part in it.

Natural History GCSE

For SMBs, such areas in Essex and Hampshire with accompanying beetle cottages (arks just for now) would be a great, though modest, start. Within 10 years, neighbouring counties could be seeing scarlet malachite beetles on their greens plus many other colourful insects and, within 20 years, the scarlet malachite beetle could be restored to its former range. The scarlet malachite beetle would be a great project for the new Natural History GCSE to get behind, incorporating metamorphic life-cycles with diverse ecological needs, habitat management and conservation and I believe that Natural History study needs outdoor fields far more than it needs classrooms. The natural world is a life raft, an ark, for our species, and yet many of its passengers are sawing it to pieces as it floats on its greedy voyage into oblivion. I prefer a greener future myself.

With love, from me to you

For me, these colourful beetles are as thrilling as any butterflies, their courtship is like the rutting of deer, but flying deer dressed in iridescent coloured robes and their hidden larval life is like a secret treasure wrapped in the precious heritage of a medieval Britain almost lost to us now and worth preserving for the sake of our own understanding of who and what we are… part of nature, dependent on nature.

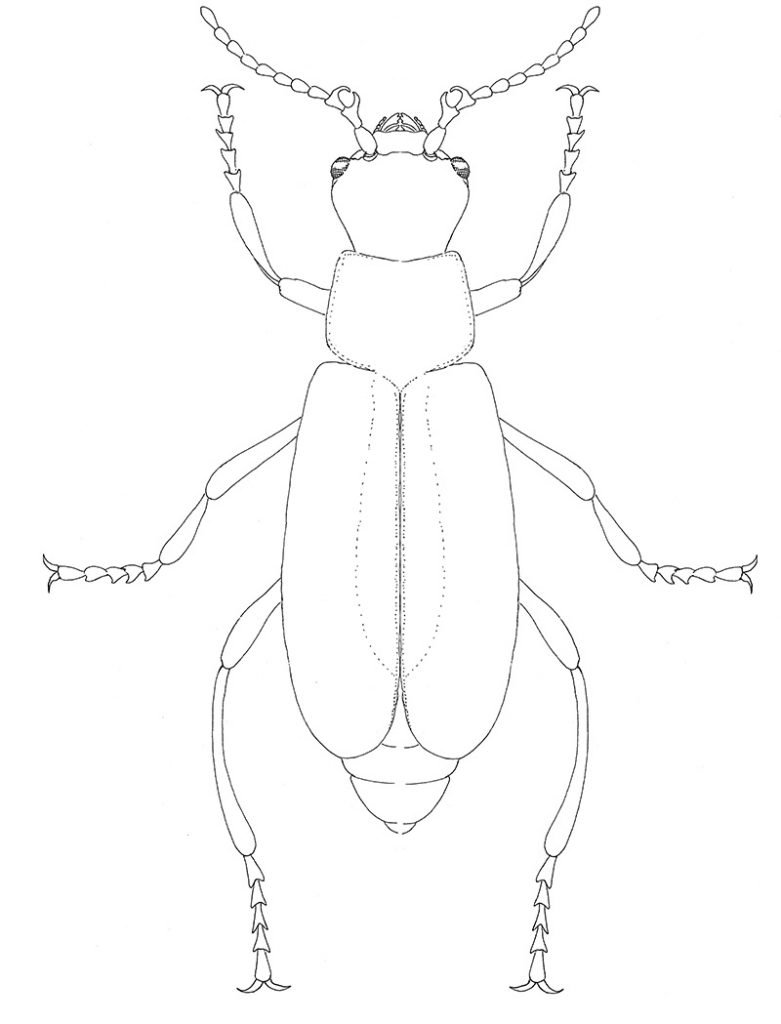

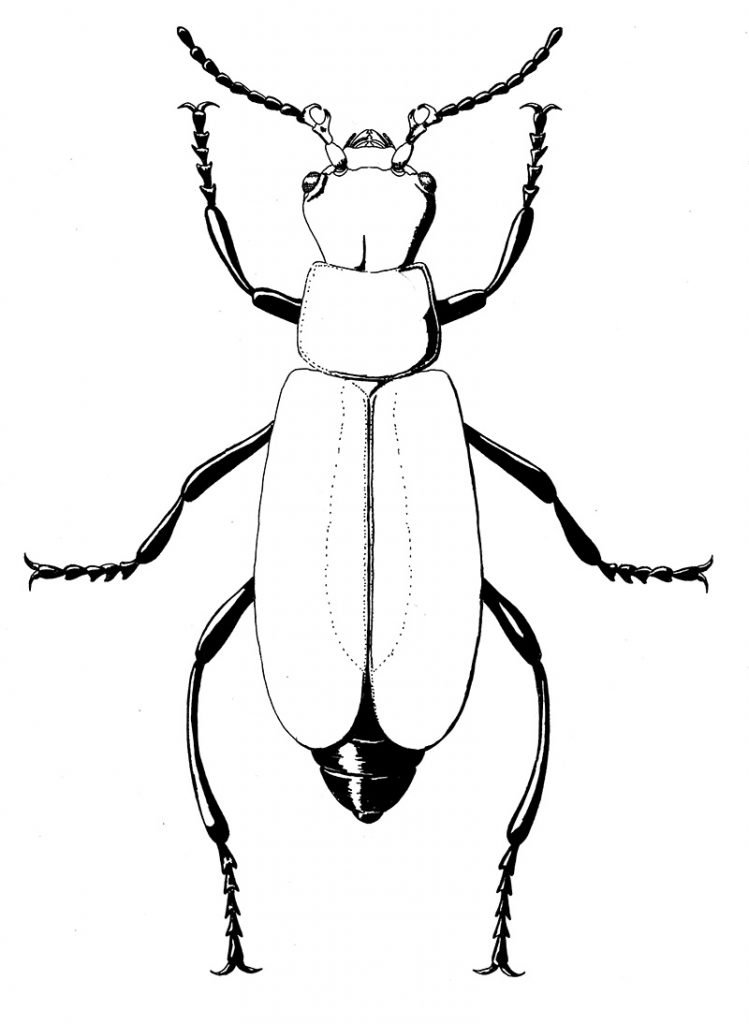

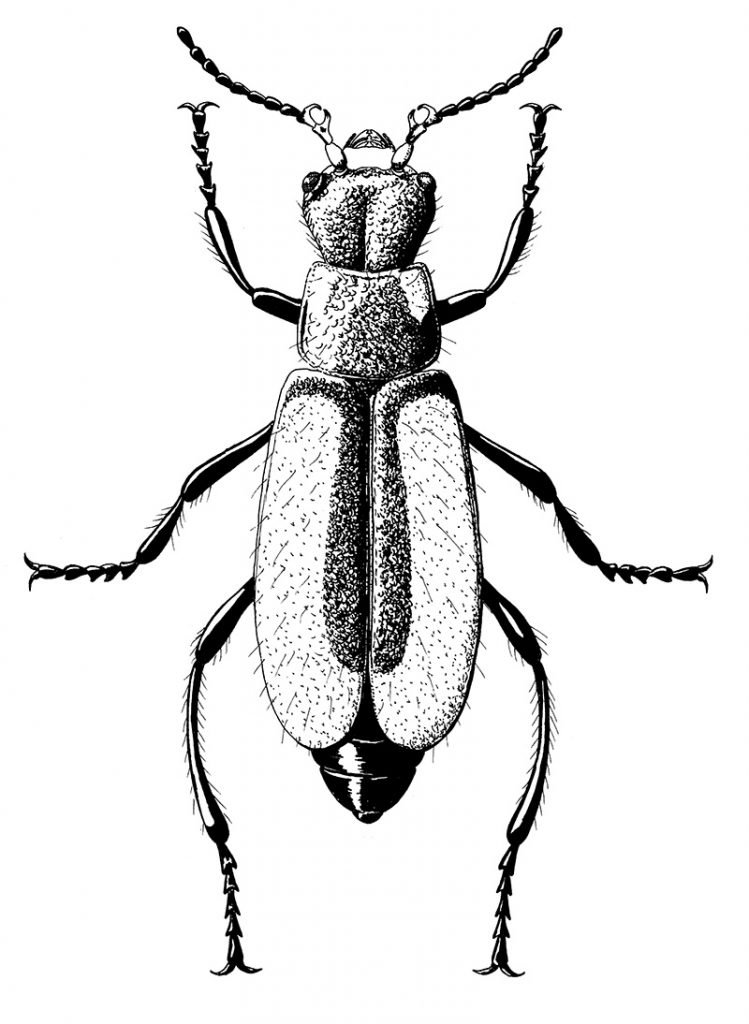

Funding and Scarlet Malachite Beetle Art

At this moment there is no funding for this project! We’d love to continue this work and save this beautiful beetle.

You can help us, we have a new prints of the beetle available, profits from these prints will go straight to the Scarlet Malachite Beetle project.

We’d also love to know if you’d like a Scarlet Malachite Beetle T-shirt?

For more information take a look at this blog post here >>>

Weird I have found these in my basement in alberta. Do they eat spider mites or Thirps?

Hi, thanks very much for this and it is very interesting that you have found them in your basement. It’s a presumption, but I presume they do eat thrips and spider mites as they seem to take most invertebrates. Here, they seem to need dry conditions but Victorian naturalists considered them to be a woodland species and all UK woods are damp!

You may know this but scarlet malachite beetles were introduced into the eastern USA in the 1800s and rapidly spread across north America. My only reference to identify the larva was from an American chat forum (someone found one in a drawer and raised it to adulthood) but I contacted a Canadian entomologist who had listed the species in a recent survey in either Nova Scotia or Newfoundland and asked him about thatch or similar substrates in which the larvae might live. I know most of the area is drier than UK so they may be able to survive in grass tussocks and under bark and the contact said he knew of no thatch in Canada and had never seen a scarlet malachite beetle larva. I wondered if shingle roofs and timber buildings may be part of the answer? Obviously it is of great interest to us how they do so well in North America but are on the brink of extinction in the UK and, apparently in Scandinavia.

I would be very interested in a description of your basement and the building if ever you have time.

Thanks again and best wishes

Ian

Hi, I have photos of the Scarlat malachite beetle that I took when it was walking on our stucco wall. Taken on June 9/2024.

So far I have come across 2 of them. I live in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. I can send you a photo if you like, just send me your email.

I was asked by a fellow photographer how they were introduced in North America and by whom.

It seems that they, as your info that they are from the Britain area.

Very interesting beetle.

Robert.

Great stuff! I studied SMBs as part of my MSc dissertation in 2005 and spent the summer of that year on a village green in Essex. At the time it seemed that thatched roofs would be likely oviposition sites , but the anecdotal evidence was patchy at best. I wasn’t aware of any of this subsequent work until a recent contact from an author who is writing a chapter on the species as part of a book project. Love what you’ve done with the ‘beetle cottages’! Also the idea of reintroducing this synanthropic insect (as per the original UKBAP!) is a powerful one. The Norfolk Broads (where i live) still has plenty of thatched cottages adjacent to dampish meadows with meadow foxtail…

Hi Rob, your report is among my treasured documents and was very useful. You were right about hedges acting as barriers to the beetles.

Regarding reintroductions… Please stay in touch!

Best wishes

Ian