Inspiring New Naturalists

Can we inspire a new generation of naturalists, conservationists, environmentalists with art?

Money making has never really been my thing. I quickly identified as a child that I wanted to work with nature and preferably in conservation; spreading the message about what I care about.

FAQs popped up after the “What do you want to do when you grow up question.”

How will you make any money at that?

Isn’t it a difficult line of business to get into?

What qualifications will you need?

As a fairly financially dis-interested, un-academic, introvert, stubborn to a fault about his interests, my answers would have been: Don’t know, don’t know, don’t know on all three counts but, as I said, I was an introvert and a polite one so would sometimes waffle incoherently or would hear an answer zooming in from someone else speaking for me.

Often I would drift away from my car and football obsessed friends, either to the countryside with my dog or to the museum. I don’t think I would ever have said a word at the museum, but my Mum spoke to the attendants and they introduced me to the taxidermist, who in turn took me on as a trainee and taught me, not just taxidermy, but art, beekeeping, observation and how to be a naturalist. Us, museum folk got on well together but enjoyed our own company just as much and were as happy working all day on a project alone, as we were working together on a larger exhibit. I moved into zoos in the hope of getting more involved with conservation and found zoo people quite similar, self-absorbed, self-contained but generous and friendly, empathetic.

David Attenborough

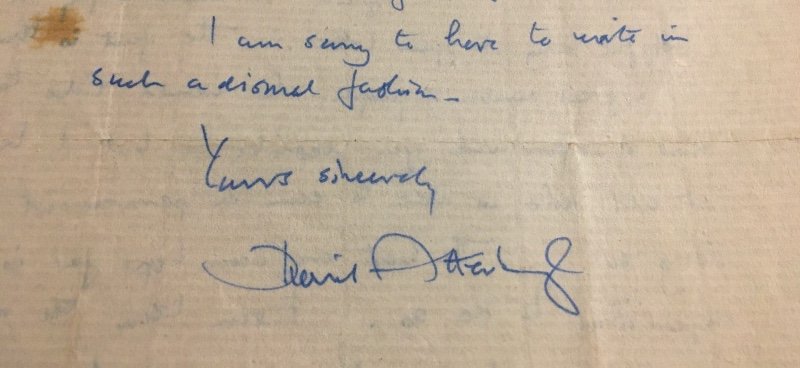

My Mum, especially, saw promise in me but was concerned about the wicked world too, and my academic laziness, and made attempts to carve a future for me. The most successful attempt was the museum one described above. A less successful one was a letter to David Attenborough to which he replied.

I was forever grateful that he took the time to reply.

Making it big in nature!

It seemed, to make it big in nature, you needed a degree. I felt incapable of attaining a degree and had had enough of sitting in classrooms being told everything is wrong or can be improved and listening to teachers disciplining unruly classmates and the unruly classmates being unruly; who needs that?

I fell lucky, in job if not in money. My boss was poor and that’s not a good sign for financial success but I never saw it like that. We did what we did because we loved it and we cared about nature. We need money but need no more than we need.

I did get into conservation. Actions sometimes speak louder than certificates and, without a degree, or A-levels, or even any O-level passes I made it into invertebrate conservation. But the funding in this field was, and remains, horrendously unpredictable for an endeavour whose greatest need is stability.

Concerned less by money-making, but by how we actually could fund the work, when funds so regularly collapsed. Also how we actually could make a difference in a world where helping our fellow species is low on the agenda. (Much of the climate change lobby and environmentalism is focused on the effects our global activities will have, or are having on humanity.) We reviewed the situation. What can we do, how can we play to our skills, fund ourselves at least adequately, and make a positive difference to the global catastrophe of disappearing species.

Up to this point in time the work of Lifeforms had been quite evenly divided between field conservation and 3D art; models sculptures and casts for museums, zoos and nature centres.

Field Conservation

The field conservation work has always been successful in action but unprofitable and any funding we did get simply helped us get closer to breaking even or adding a small amount, at best, to the profits of the artwork. But the work was actually saving species, the ladybird spider in particular was exemplary, up from a single site when we started to over 10. Do we give up just because it doesn’t make us any money? It was not well publicised but publicity does not help critically threatened species if it stimulates interest in people to see them for themselves or to take up your time for media stories that don’t pay. Giving up seemed unthinkable; was there something we could do, more important, more effective, than on the ground field conservation?

3D Artwork

The 3D artwork was effectively awareness work, using museum methods to raise awareness about the natural world. The clients were keen to deliver that message but they wanted durable art, often light-weight because it was to be mounted and easily fitted too. This meant plastic (resin and glass-fibre) nine times out of ten. Used in museum exhibits intended to last over 100 years, durable resin was welcomed and it was worth enduring its toxic fumes and stickiness. But resin is not a smell that outdoor folk tend to enjoy, nor is it a welcome alternative to smells like beeswax or as malleable and forgiving as clay or plaster. The primary customers now were zoos and whilst this conservation awareness material could be viewed and touched by over a million people a year, it had to be durable enough to withstand that attention. The attention was more like idle entertainment than the delivery of a successful awareness message. One regular client had moved from calling the models, models, specimens, sculptures or educational artefacts or visual/tactile aids to simply calling them resins and a plan for an exhibit would have a blank space on it with the word ‘Resin’ inserted in the space often followed by a question mark. Whilst good for business the flow of exhibits increased with some, only a year old being replaced by others to keep the customers entertained and making repeat visits. This all seemed hypocritical. Perhaps we could do better?

Casting

We looked first to our casts in about 2008. Over the years, I have amassed a large collection of replicas of interesting things I have found. Casting is a museum method and part of the repertoire of the modern museum taxidermist (in small museums) which includes not just ‘traditional taxidermy’ – known to most as ‘stuffing animals’ – but the painting of backgrounds, sculpture and model making of animals and plants and also the aforementioned ‘casting.’

Animals with fur or feathers, and some with scales and exoskeletons, are well suited to preservation by taxidermy. You won’t catch me saying, stuff, stuffing, to stuff, I stuffed or any other stuff like that in a methodological context. Many animals with scales, soft-bodies or body parts as well as many plants and fungi suffer from shrinkage, collapse and discolouration. In these cases, most of the earth’s lifeforms, preservation of an accurate portrayal of the specimen is best accomplished by casting which captures form (shape) and texture as reliably as photographs. Effectively, we manufacture a fossil and, just like a fossil, it could last as long as the lifespan of the earth. Better than a fossil, it preserves the specimen before soft-parts have been eaten or decomposed.

Saving Artefacts

The downside is that colour is not preserved but colour would be lost from such specimens anyway. Working in museums I was asked to replicate fossils for display and to sell in gift shops. Little plaster trinkets for pocket money as educational mementos, souvenirs of a visit to the museum. It struck me that the same could be achieved with non-fossilised a species still alive today and that we had the material to do it with. Most zoo, museum and nature gift shops are stocked mostly with plastics or books and there is very little for the principled or hands-on adventurous young naturalist who doesn’t just want a souvenir, but wants to learn, to absorb to get closer. Coupled with that is the outdoor experience. Pick up a dead crab on the beach as a young child and most of the party with you are likely to remark on its pong, it’s yukkiness or similar. The same can be said of a dead toad squashed on the road. To a naturalist they are fascinating artefacts with amazing textures but, unlike seashells, feathers, or leaves, they cannot usually be taken home and put on a curiosity shelf. Casting solves this, it can often be done in-situ and the smelly specimen left behind and it has the added bonus of being re-replicable; copies can be made. We felt that such copies could be handled by curious children without fear of attack, infection, smelly fingers or of damaging a delicate specimen.

Cost and Bubbles

The problem we had, or still have, was a combination of cost and bubbles. The process is a bit fiddly and, if done quickly and in mass production, the likelihood of bubbles sneaking in increases. For one-offs, we take great care to be sure they are bubble-free but if we want to sell them for pocket money we have to reduce the time scale. Bubbles don’t bother us, we can fill them, but filling takes time and again increases the cost. Disposing of bubbly casts does not fit our environmental principles. Additionally, casts need to dry and once dry can erode through handling unless they are sealed, which again pushes the price up beyond pocket money. We like to encourage people to paint their own casts, but a wash of paint reveals the textures of the specimen much more than they can be seen on a plain monotone cast. A coloured wash and sealing can be combined as one but the time factor is still there and the wash can often need repeating or reveal previously invisible bubbles; invisibubbles. It’s annoying, it’s a conundrum.

2D Art

At the same time, I was increasingly being asked for 2D art. On one occasion I sketched an idea for a sign for a client and the next time I visited, the sketch had been carved, mistakes and all, onto a bill-board sized wooden panel mounted on posts to inform people they were entering into the wetland section. Those who can draw often don’t appreciate it. 2D is an easily accessible art, easily re-produced and accessible to all except for blind and partially sight people. I consider myself a naturalist, not an artist but perhaps 2D was, in some form, a way forward, a way to make a difference.

Spreading the Conservation Message

We felt that growing our own way and exhibiting in galleries would not reach the people we want to reach. It would reach the privileged already converted and in a place where children are largely absent or very controlled. We knew our 3D models and casts were special, are special. But they were difficult to deliver, are difficult to deliver, to the public in an environmentally friendly and affordable way. Perhaps the way forward was to allow people access to the 3D material but let them take away something else, something valuable, something with a positive impact. How could we make the story of the great auk more visible than in a gallery or shut away in a book? We love books, we encourage books, but they can be very private things. We came up with two key observations which are pretty obvious.

- Most people these days get their information off the internet using computer or phone. They talk about the information and share it much more than they would or could from a book or gallery.

- Almost everyone wears clothes, they exhibit their style their taste, in what they wear. Why not use clothes to deliver a nature awareness message, a conservation message?

Lifeforms Art was born.

It was to deliver 2D art and awareness to wear in order to spark discussion.

The idea was to create something fascinating, to delve into subjects seldom visible or brought out into the open and to invoke memories in parents and grandparents to get them talking to their descendants about nature in an excited way, not just interested, or memorable… excited.

Stickleback

Great Auk

Octopus

Cetaceans

Steller’s Sea Cow

Leatherback Turtle

Crabs

Jellyfish

Engaging with youngsters

Now to the core of the matter. How do we reach and inspire potential young naturalists when we have only a moment of their time to do it in. David Attenborough has it easy in this respect, I’m sure David wouldn’t agree, considering the time, effort and money that goes into an Attenborough production. But he has about an hour per show of prime-time TV to get his message across backed up by the massive advertising machine (yes, advertising) that is the BBC.

Can we come close to that without the glowing omnipresent power of television. Can we reach that number of people or can we give more to fewer individuals without ruining ourselves.

Here’s how we do it, it’s just our way but for us, it’s magical. Camouflaged amongst stalls, including conservation trusts selling polyester cuddly toys and organic producers selling natural skin products, turned wooden bowls and chopping boards and all sorts of other ‘wonderful things’, we display our wares; T-Shirts, prints and notebooks primarily; but also casts. One of our pictures looks like a group of penguins, another like a walrus or a dugong or something in between, another is clearly a tiddler in a jar, and another is a crab, threatening its captor with claws outstretched after climbing out of the tin can it has been placed in. Our logo is Curly the octopus a manifestation of otherworldliness and multi-tasking in a being composed largely of spirals. The images are meant to fascinate children and to get adults talking; to lure families into a shared experience of nature and to empower them as naturalists; but you can’t just pounce on them, they’ll flee. They are shy beings and approach the bait slowly, cautiously.

Empowering Naturalists

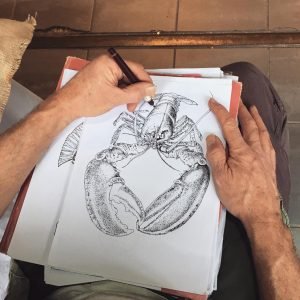

“Arr, remember catching tiddlers in a jar,” one might say, standing 3 paces away from the stall.” Or, “look at the penguins, I love penguins.” At this point they often have not noticed me although sometimes it works the other way round. I try to sit as quietly as possible in front of the stall or in an accessible position and draw or work on a cast. Kerry and the boys usually man the stall while I demonstrate art, my inability to count accurately or use a mobile phone to conduct card sales is quite debilitating, so I stick to what I’m good at or, more accurately, what I’m happiest with. Any one of them can take over the drawing.

Our ‘penguins’ aren’t penguins, our ‘walrus’ is not a walrus. They’re a Great Auk and a Steller’s Sea Cow.

Soon enough I can sense someone looking over my shoulder, as silent as a predator, I’m working not with the sweeping strokes of a flamboyant artist but with the careful, fidgety movements of a naturalist. I am placing dots of ink on a piece of paper, dot after dot after dot to make up a picture. Though painstaking, the method is fairly easy and can be highly accurate because, at one dot at a time it is difficult to make any horrendous mistakes. It’s one of those things that looks much more impressive than it really is. I was told to call it, and always have called it, stippling.

I glance at them respectfully and say “hello.” Anymore, than that could be too much and scare them away. They are fearful of the hard-sell, we don’t like it ourselves and, whilst sales help, it is not our main objective, we want them to enjoy the experience and take that away; we want them to follow us.

If hello doesn’t scare them away, I follow it, a few seconds later, with one of three questions:

Do you know what it is?

Do you like crabs (or whatever the species is)?

Do you like drawing?

Sometimes the questions are unnecessary and they begin to talk but if not, the questions do the trick and we’re away. Such people, children or adults, often have confidence issues. They want to study biology or they want to do art but they don’t think they are clever enough or skilful enough or patient enough. To be honest, the latter is by far the biggest obstacle but is the easiest to identify and is not insurmountable.

Wildlife Experience

I explain that I am a clumsy, un-academic person who always takes the easy route if possible. I got to this position by hiding away and drawing or stalking wildlife. Practice, practice practice. That’s it, the dart has been fired and the confidence drug is pumping around their metabolism. We show them casts and illustrations. We let them have a go at stippling and we talk about the species they are interested in and how they might get closer. Sometimes, they will tell us then about their exotic holidays, their zoology degree or an exhibition of paintings they have put up. It feels initially, that we cannot help these people as they have surpassed us, but the truth is that this is rarely the case. We can often help them be more satisfied with wildlife experiences closer to home and to use their experiences to help wildlife and to help other people get into wildlife sampling by confidence boosting or setting an example. Such people can also help by spreading the word about us or by actually buying our stuff.

Reaching the younger generation

Our greatest rewards are the little boys and girls, fascinated by nature. Who have never before seen what they are looking at, never talked to someone who works with nature or in nature art and who see the possibility that they could do it too. It’s better still if they have been traipsing round bored, doing what someone else wanted to do and with no thought of seeing something interesting that day but they leave us with a happy glowing face. Money cannot buy such a rewarding experience, for them, or for us, and off they go to save the world.

We introduced our children’s T-shirt range after one such experience. It was the end of a long day and the numbers of people were dwindling. A quite exhausted looking mother and son arrived at our stall. The young man was about 8 years old and he’d had a day of wandering around looking at so many stalls, he spotted our octopus cast and burst into tears. As did we almost! He wanted to handle the octopus, to talk about it, to learn about it. After 10 minutes of chatting he walked away from the stall with the octopus cast and armed with knowledge about this amazing creature, he was so excited to share his new found information. We decided then to add children’s t-shirts to our range, not with images of cartoon animals or simplified versions, but with accurate artwork of the creatures they’re interested in.

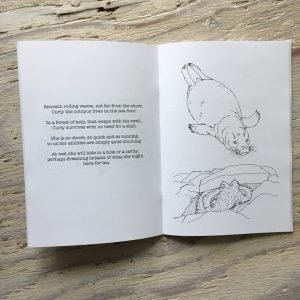

And so to the story books

Is that all? Not quite, we have one more trick up our sleeves which, for want of a better word, I’ll call fun.

I grew up with readers, and they read to me. I was led into reading, ironically, by anthropomorphic motor vehicles; notably, tootles the taxi; “I’m Tootles the taxi, I’ll give you a ride, just put up your hand and then jump inside.” I loved the rhythm and the detail. Then Yertle the Turtle (and other stories) arrived in the house. Dr Seuss could tell a cracking story with wit, humour and moral wisdom in beautifully flowing rhyme. I make no claim to be a poet, I don’t understand proper poetry, but have always enjoyed converting thoughts to rhyme. We wondered if we could convert otherwise dry and difficult to read text into enjoyable language about nature that flowed into the brain and lodged there as easily as Tootles the Taxi and Dr. Seuss.

So, we’re using another art form, rhyme to help create new naturalists. We don’t yet know if it works but the feedback, mostly from young men and retired women, has been very positive. They go a bit like this… “Luth’s are the largest of turtles there are, they dive very deep and they swim very far.” Or, for Curly the octopus… “and there invisibly, our Curly lies, the only parts not under sand are her eyes. Hidden from danger, but perhaps I should say, that Curly is also hidden from prey.”

We place insets and diagrams among the pictures which can be coloured in, with the intention that the book is a handbook about, leatherback turtles, octopuses, seahorses, jellyfish or shore crabs and inspires children to spend more time on them. We want to empower children with the knowledge about nature in a way that stays with them and that that they feel confident to share.

The long term aim is that they will want to find out more and ultimately they’ll go on to help preserve a more natural, natural world for us, themselves and our shared descendents and successors. Time will tell.