Bats

Arrr, (I utter the sound affectionately) bats. Bats, bats, bats.

I don’t pretend to understand bats and have no ambition to fathom out their World, their Umwelt.

But (or perhaps ‘bat’ in the Queen’s English), I have loved and been fascinated by bats for almost as long as I can remember. I say almost because I can just remember discovering them.

Around about my 4th or 5th Christmas, my obsession with animals already well-recognised, I received, from that well known night-flying mammal Santa Claus, a book.

Animal Encyclopedia

The book was the Hamlyn Children’s Animal World Encyclopaedia in Colour. I hugged the book almost continuously like it was a teddy bear. I flicked through it at every opportunity whilst nagging my Mother and Grandmother to read sections of it to me. I was almost immediately drawn to Page 44, a sort of centrefold of bats. A type of animal that I had never seen or heard of before.

I asked Mum what they were…

“What are they Mum?”

“They’re bats love.”

“What are bats?”

“Well, they’re like flying mice. They’re sometimes called Flittermice. They fly at night and sleep upside down in caves and church spires with their wings wrapped around them. Some of them are bigger and are called flying foxes. Er… I think.”

This was pretty much the sum total of my Mum’s bat knowledge but it blew me away to batdom forever. I guess if Jeremy Paxman said…

“Here’s your starter for 10, fingers on buzzers. Sometimes called flittermice and flying foxes, what is the common name of the mammals who sleep hanging upside down in caves and building with their wings wrapped around their bodies. They comprise the mammalian order Chiroptera and no conferring.” Almost everyone would get it.

But to a child’s mind it is even more. Children love learning new things pretty much up to the point when they’re told not to. Old Mac Donald’s farm and most city streets have plenty of four legged mammals and feathered birds. But flying mice can come as a surprising bit of diversity to a child. If not all children love clowns, most at least, love a bit of slap-stick and otherwise unusual behaviour. Cows stand on their 4 legs and moo, dogs on their 4 legs say woof chickens, on 2 legs like us, go cluck. But bats, fly in the dark, hang upside down and make sounds we can’t hear. They have a reputation for inhabiting those places that send a little shiver up the spine; church belfries, caves, mine shafts and old dark woods. They are the dark side of animal life.

The night flying mysterious and secretive Santa, a flying mammal towed by flying mammals, who I completely believed in, had brought me this book. He obviously wanted me to read it. He had brought me bats and I was hearing his message loud and clear.

Introducing Bats and their Umwelt

Once we’d read the portion in the encyclopaedia and looked at the pictures, we knew a whole lot more. Bats are not just one type of animal, or two, Flittermice and flying foxes; they are a ‘family’ of many ‘species’. It turned out that bats are not blind, as Mum had been led to believe. They, as a group, are the only mammals that can truly fly. Flying squirrels and lemurs, we discovered, only glide although they are no less spectacular for that. Although bats can see, it does not do them much good at night and so they use sonar. They see with their ears by uttering sounds which bounce off objects (and prey) as echoes and return to the bats ears. Their brain turns them into a picture of its world. Its Umwelt.

Umwelt is not in the children’s book or many books at all so let’s circle in on it for a better understanding. This is my version of our long-term relationship with bats and their journey to the here and now (or hear an’ how!). Millions of years ago, we share (or shared) a common ancestor with bats. If you trundle down our lines of parents, grand parents, great grandparents etc as if they were lined up at a wedding to greet guests (and nobody ever died!) we would, after a lot of walking, hand-shaking a small talk, come to our common ancestor with chimps as our lines of descent converge. On we trundle, more monkey-like now, converging with gorillas, orangutans, gibbons and then monkeys and lemurs.

Soon after this (or before really), we’ll meet a Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrreat grand parent who looks a bit like as modern day tree shrew. Who, though identical to us at one time had (or has, or will have) descendants who had something resembling the following adventure.

Chats with Bats

If bats could speak our language (or we could speak theirs) we might say to each other… Ah, Great10 Grandma tree-shrewish is your grandma too, eh? I don’t remember her but I know everyone loved her. She was very kind and hard working and important to us all.

Being small and primarily a sniffer and listener. The safest time to be out and about for us was at night. Our best source of food was insects but we liked fruit too, quite omnivorous we were, much like monkeys and apes are today. Some of our kind were happy like this and changed very little. Others became more fruit minded and still others went off nibbling harder foods like nuts or chasing down other animals eventually becoming mice and bears. We became quite adept at leaping from branch to branch to escape predators and also to catch prey or move from one fruit bearing tree to another.

Around about this time, we discovered a clever trick (or it discovered us). Our method of communication was ultrasonic calls, which allowed us to communicate without other sounds interfering and without attracting many predators who could close in on more audible sounds. As we chattered away, hunting in the night, it turned out that we could hear our own sound reflecting off prey and objects and could use them to our advantage. It was imperceptible at first, we never really thought about it, but those of us who could do it, survived better than those who could not and soon the whole population was doing it. Those of us who were better at it did better still and soon it was our main navigation tool.

Taking the leap

Our mouths and ears showed us the world in a way that our eyes and noses could not. It was especially useful for flying insects between trees who, with our biggest leaps, we could catch as we leapt from one tree to another. But we soon were able to tell from a distance whether trees had fruit (even upwind) and whether other proto-bats or predators were in them. Those of us with the flappiest flanks and most webbed fingers could leap that little bit farther and did better and so had more babies who survived better too.

After a million years or so of this, we looked distinctly un-tree shrew like and more like a flying lemur but with long webbed fingers which we used in our leaps to ‘bat’ insects into our mouths. Our leaps had become much longer and would probably be described as gliding. The best of us glid very well and some individuals could push down as they approached an insect or object and propel themselves just a little bit further. These guys did very well, survived longer and produced many more babies (who’d survive and breed), some of whom could do the pushing air trick quite a bit better. Their descendants perfected this, their webbed fingers joined, through their webbing with their arms and ankles and they became capable of true flight.

Freedom of Flight

Giant webbed hands are a bit awkward for climbing and we found it easier, and safer from predators, to hang upside down. From this position we were difficult to catch by climbing and we could leave our perch in a flash. The freedom of flight gave us great opportunities. Those of us who preferred fruit could travel long distances easily to find it and we could diversify to other foods as well, nectar, terrestrial vertebrates, fish and even blood being able to visit dangerous feeding grounds in the safety of darkness and retreat by day to safer places.

We had the freedom to choose these places. Branches were good, hollow trees were great but restricted our size or numbers but best of all were caves. Our enemies, cats, weaselly things, snakes and monitor lizards struggle, or find it impossible, to climb cave walls and find little other food there. Caves are often a bit cold for reptiles anyway and inaccessible to most birds who mostly need light.

It turned out that our smaller family members, focussing on insects were well suited for spreading around the whole world whilst our larger folks did best in the tropics as did the medium sized guys who went for bigger prey. Smaller bats can hibernate, switch off for winter and this has enabled them to colonise northern lands and even inside the arctic circle. The equivalent areas in the south are mostly ocean or remote islands.

Perhaps from one species, we diversified into more than 6495* species worldwide comprising about 20% of all mammals. If all mammals were one that would be around about one leg, or a head!

(*Stat updated thanks to info from worldanimalfoundation.org)

Back to the Umwelt

So anyway, I mentioned umwelt. Well you are sort of in it now or you have a toe in our Umwelt at least. Umwelt is a fairly modern human term and I’m going to let a modern human expert explain it for you, just in case you don’t know the term, coined in about 1915.

Jakob von Uexkull, a German biologist drew attention to the animal point of view, calling it its Umwelt. To illustrate this new concept (German for “surrounding world”), Uexkull took us on a stroll through various worlds. Each organism senses the environment in its own way, he said. The eyeless tick climbs onto a grass stem to await the smell of butyric acid emanating from mammalian skin. Since experiments have shown that this arachnid can go for eighteen years without food, the tick has ample time to meet a mammal, drop onto her victim, and gorge herself on warm blood. Afterward she is ready to lay her eggs and die. Can we understand a tick’s umwelt? It seems incredibly impoverished compared to ours, but Uexkull saw its simplicity as a strength: her goal is well defined, and she encounters few distractions…

Umwelt is quite different from the notion of ecological niche, which concerns the habitat that an animal needs for survival. Instead Umwelt stresses an organism’s self-centred, subjective world, which represents only a small tranche of all available worlds. … Some animals perceive ultra-violet light, for example while others live in a world of smells or, like the star nosed mole, feel their way around underground. Some sit on the branches of an oak, and others live underneath its bark, while a fox family digs a lair among its roots. Each perceives the same tree differently.

From: Frans de Waal in Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are.

As a field conservationist and conservation breeder, it has been my job and my duty to try to see (or feel) the Umwelt of other organisms, to get inside their world and perceive how they feel and, more importantly, what they need. I think the first time I did this (without knowing it), was the first time I saw bats.

Frans deWaal

My first meeting with bats

We had been on a family walk and dusk had fallen. It was early autumn, a windless evening, and we were on the finally stretch, nearly home. What, I assumed was a small bird went zipping by but its flight seemed not quite bird like and as much like a moth as a bird. I was six years old. The being had come in close to us but had just as quickly disappeared over the hedge between two big old oaks. Nobody else paid any attention but I had snapped into hunter mode, like Robert Shaw’s Quint in the film Jaws when the fishing reel moves on one click.

“What was that and where did it go? Could it have been a bat?”

I slowed my pace and announced in my squeaky little voice that I thought I might have seen a bat. Optimistic possible sightings of animals I wanted to see had come bubbling out of my mouth for some years and I wasn’t taken that seriously but, knowing this, I was learning to keep my thoughts to myself unless I was fairly sure; and here it came again.

Circling one of the oaks the little moth-bird fluttered straight towards us along the track, then crossed the hedge at head height and looped back on itself, looped again and carried on. I saw it wings against the sky in the dim light, they were membranous, see-through, skin. It was a bat!

Everyone saw it and stopped.

“It is a bat, I said, it’s a bat, it’s a bat, it’s a bat.”

“I think he might be right love.” Said Mum to Dad who responded expertly…

“It’s possible, it is getting dark.”

The creature was still in sight and it circled us looping time and time again and then flying right over our heads with, just for us, a short glide. There was no doubt now, to anyone that this was a bat. So, we stayed and watched in the fading light as it flittered about. It appeared to be flying a circuit and coming back to us at regular intervals. When it returned every 20 seconds or so (for about 10 seconds) it was a little harder to see each time but I could hear that it was accompanied by a sound; a series of very high pitched repetitive squeaks. I could hear it!

From what we had read, people cannot normally hear bats as they are ultrasonic but I was absolutely sure what I was hearing was the bat. Another turned up and I could hear it too. Have you ever tried telling someone that you can hear something they cannot? I felt almost magical but mad at the same time, I could hear them talking when others could not. Just like Santa and the fairies could hear me, but I could not hear them. This is the world I grew up in, my Umwelt, one of reality mixed with fantasy and nature mixed with a man-made and controlled world.

Bat magic

None of my family or school friends had ever knowingly seen a bat and yet here they were less than a mile from home. Had I found them or had they found me. My world had changed in an instant from one where bats were rare and unseen to one with bats in it that I could see and hear. The loops appeared to be hunting manoeuvres, they were detecting insects and turning to grab them in the blink of an eye. I was startled by the speed. Their wings beat, not like most birds, but more like an insects, but their flight was like nothing else. Birds I had seen took fairly straight flights and insects tend to do the same with the exception of hoverflies or butterflies and bees visiting flowers.

These bats were turning figures of eight in front of us and flying around, not just in circles, but around us. I thought at the time that we were simply walking through their world but it is highly likely that they were checking us out and benefitting or hoping to, from the insects we were both stirring up and attracting. Could I think as fast as they were flying, could I turn and catch an insect so quickly if I saw one in my peripheral vision? Aw… my feet lifted from the ground just then; are yours lifting too? But wait, they were not seeing the insects but hearing them, and not really hearing them but hearing an echo coming off them.

My eyes followed the bats in the dimming light but my mind followed closer still, trying to keep up with them, catch up with them and even overtake them and predict their moves. I took these thoughts away with me and enacted them later, over and over again, trying to be a bat or be with bats.

That night and many nights after I dreamed about them, being amongst them, having bats as pets or friends. I was in deep. My bedroom wall was covered in bat pictures cut from magazines. Stuck with blue-tack as if they were hanging naturally from shelves and walls; my bedroom was my best attempt at a bat cave before I was told there was a batman.

I liked Batman but he was no Santa Claus. He couldn’t fly (not even glide very well) and seemed to be active more by day than night. He was not all that bat like either. His wings were floppy, he made little or no use of echolocation (a missed trick or what?) and plodded around bipedally rather than scampering around on all fours and effortlessly climbing buildings. When he did climb buildings he appeared to be plodding again, up a building that was on its side.

Whilst the amiable Adam West may not have been the most dynamic choice for the action hero, mimicking an active animal in a dynamic duo; Lon Chaney would probably have been a better choice, it did set a marker for how bats and humans might compare and I was much more keen on the were-bat than I was on the bat-man. And here we go…

Bat man – into the bat’s Umwelt

Being a Bat

I am in the air. The wind rushes past wafting my silky soft fur. I am tactile, so tactile. My fur tells me my direction and angle but it is of minor sensory importance to me. It mostly keeps my active little body warm, and I need it, my muscles need good insulation to serve me well in flight and my arms, legs and tail, being bare, lose a lot of heat. Birds are better off in this respect, they are feathered all over and feathers have super-duper insulating properties but birds are like you humans, almost completely reliant on light and the visible world. My world is different. Fingers are for feeling and my long fingers feel the air which I grasp and caress more like water than the gas that it is.

Your slow world plods dozily by as I zip thorough the firmament like a dolphin in the sea. I feel the pull of gravity, I use it to plunge and swoop but I feel the support of the air more and my hands climb it and ride it. The gossamer-like membrane of my wings, from finger tip to ankle is a sensory organ. You may follow your head or your heart but I think on the wing, here and now in the sky at least. Each wing is both ear and antenna and tells me my direction, altitude, camber as well as air temperature and barometric pressure. Sounds vibrate the taught skin allowing me to hear, without using my ears.

Ah, I love the feel of the air, I love changing direction, I live for swoops and loop the loops.

Using senses

Close your eyes and breathe in through your nose. Can you smell what is around you? Can you smell different things on your person and within the room or landscape you are occupying? Can you smell other beings? Do you notice these things more because I mention them and because your eyes are shut? Your attention to smell, is about the same as my attention to sight. I can see all things but images are secondary or less to me. Most of the world I perceive, comes to me through my wings and my ears. My head is a toolkit for navigation. A hammer and anvil that works like and engine and two satellite dishes that map my way.

I don’t think about this in pieces any more than you think about the single letters in the words that you speak and I speak to the world and it answers. In your visual world you borrow light from the sun and read its reflections from the objects it hits. In the dark you are lost and must use your fingers and other senses. I recommend it, fingers are good in the dark.

Creating a picture of the world

For me it is different, I don’t need the sun, I send out my own light as a series of sounds. I control its brightness, colour and direction. Imagine a single letter of that sound. It travels away from me at 767 miles per hour. It is slower than light but easily fast enough; I don’t think about its speed, do you think of the speed that light hits your eyes and that it is 8 minutes old by the time it reaches earth from the sun. I talk to the world and it answers. One letter, let’s say it’s a D, gives me one picture but it is already more 3 dimensional than yours. The sound hits every object around me and it bounces back. The further the sound has travelled the dimmer it gets and the longer it takes to travel back.

So my answers come back as individual messages, prioritized by proximity. It is clearer and more accurate for me than seeing, it is as if I am feeling the world around me in intricate detail and I can hear more than I could ever see in that single sound. That one letter I emit brings back a photograph of the world around me but it is more than a photograph. It tells me whether trees are solid or hollow and if that dark patch on a photo is just a dark patch or a hole. It tells me the precise distance of everything by the time each sound takes to come back.

But that’s just a fraction of a second and one letter, D for distance. I can emit up to 20 Ds per second which return to me as a 3D video of the world as I move through it. If I emit Fs, (which I can do simultaneously with Ds in special bat-words) I can locate and identify food more readily. I can ‘see’ the volume and water content of the food like ingredients on a tin can and decide whether it is worth pursuing.

My brain is so fast that the question is answered in a fraction of a second too like a green light for yes, chase it and a red light to ignore or avoid. I can send out broad signals to ‘see’ my surrounding world and predators and I can emit a beam of sound to focus on prey or my hole in the tree. Are you following me? I’m worried that you’re not.

Now it’s your turn to be a Bat

Let’s try something more personal to you, and think fast.

You are in a plane at 20 thousand feet and, whoops, I have just pushed you out. You are falling without a parachute. There is no moon and only countryside below, it is pitch black and you are falling. Your rate of descent soon reaches about 130 miles per hour. Try not to panic, what use will it do? Even as a human, a none flying animal, you can make some assessments and adjustments to your situation. You have some sense of gravity and can tell which way is down and which is up. Your ears, skin and hair tell you that you are travelling a lot faster than normal or you are in a very strong wind.

Hold your arms tight against your body and your legs close together and you feel the breeze pick up as you accelerate downwards with reduced resistance to nearly 300 mph; eek, you need to slow down. Spread out your arms and legs and you can slow yourself, through wind resistance to about 80mph. By slight movements of your hands and limbs you can change your position. The preferred position for most is face and belly downwards, pointing in the direction of travel, with arms and legs out like a starfish.

Can you feel the air rushing past? Can you feel it passing between your spread fingers?

More Bat Magic

You may not feel lucky right now but in a way you are. Hopefully, you’ll thank me for pushing you out. The planes horrible drone fades into the distance as you part company. On the last full moon, you were bitten by a magic bat (don’t try this for real, just enjoy a bit of fantasy!). Although it is very cloudy tonight, it is full moon again and you are about to go through your were-bat transformation. Let’s get this first bit over with.

Becoming a Bat

The few clothes you were wearing have blown off with the wind velocity and are fluttering down somewhere above you but, feel your body. You are in a sort of furry leotard and a furry flying hat with holes for your ears. Don’t be embarrassed, nobody can see you and it is warmer than what you were wearing.

Feel the thick fur, tug it, it’s real and it is warm. On your chest and tummy the velocity, or wind speed is pressing the fur flat against you. At the sides and on your back it flaps about wildly. You don’t need to think hard about this, you can feel your direction of travel. Look, if you prefer to have kept your pants on for this it’s OK, batman does. I’ve never seen a bat in pants though and I think you’re whimping out just a bit.

It’s quite scary falling at this speed (pants or no pants) and there is still time for you to curl up into a foetal position and perhaps suck your thumb. This is probably the best first step to calm you down. Your toes are curling, literally curling, is it fear. No, the toe-nails have become hooked claws and your toes have grown to a similar length. Well, at least you have landing gear! Not the sort of thing you want to hear a pilot say; “well, folks, on the bright side at least we have landing gear….” aaaaaaaaah! Your toe nails, by the way, now have a special combination of tendons which cause the foot to grip on contact, so when it come to it, you can hang without having to think about gripping. Gripping, of course, is useless in your predicament, but you never know.

Falling through time

We are all falling really. As individuals, as species and as ecological assemblages, we are falling through time, and are destined to ‘hit the ground’ eventually. In your current situation, hurtling to earth, you might be thinking, why did I fly in the first place? But that won’t help. You need either solutions or contentment that your bit is done. Ordinarily, we have more time to plan our future and, as a species we have more time still. Can we, as a species, fly alone or do we need our ecological assemblage (and greater wisdom) to carry us aloft? Our ecological assemblage is in tatters. We’ve ripped off the bits we want or need, crammed them into our aeroplane and flown away, but, perhaps metaphorically, our aviation fuel is running out and we need to adapt or perhaps to find the ground again.

YOU HAVE BEEN FALLING NOW FOR SEVERAL SECONDS BUT DON’T WORRY THERE IS STILL TIME. TRUST ME,

Thumbs up!

Sucking that thumb is very calming. But feel your thumb changing. It is becoming too big for your mouth and your thumbnail is growing and curling into a hooked claw. Let’s go back to the sky-dive position now, facing downwards, thumbs up. Your ears are growing now, really growing and each one is soon twice the size of your head. Their dish like shape allows you to control the position of your body with your head as if they are sails. That’s not really what they are for but do you feel yourself gaining control of the situation you are in? You plummet onwards, downwards. It’s fine, it’s going to be fine.

As your ears grew, you may have felt tingling changes in your nose and throat and perhaps a slight feeling that you are thinking differently. You may be falling but you feel more at home now. You understand your direction of fall and how you can, within reason, control your speed. Spreading your fingers with outstretched arms you can feel the air rushing between them. It is particularly noticeable at the bases between each finger; a lovely cool feeling. You call out. “Ha!” and in an instant see a picture. It looks like an aerial photo. You call out again; let’s use that D for instance; D for distance.

Using sound to paint a picture

The sound hurtles away from you like a bullet made of sand and begins hitting objects and bouncing back. It hits, and returns, from the nearest objects first and most strongly and a cinema lights up inside you head. You can’t just see every tree, every wall, every dip and rise in the landscape, you can feel them. You know their exact distance, size and texture just as if they have numbers on a 3D image. Solid objects are opaque but hollow ones are transparent and things filled with fluid are translucent. By repeating the Ds, DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD, you create a cinematographic reel of the ever-approaching landscape below. You are scanning that landscape now. Perhaps there is a possibility of plummeting into something soft and squishy and actually surviving.

You are not unfamiliar with interpreting your world through sound. Knocking on an object with your knuckle will tell you if it is solid or hollow and its material; wood, glass or metal etc. Knocking on a door (the door of your destiny perhaps?) might tell you whether the room beyond is carpeted and whether it is big or small. Listening to someone on a phone or radio interview you will often be able to tell if they are in a bathroom (echoey and ceramic), kitchen (echoey and metallic), Swimming Pool, (echoey and a bit wobbly) or church or cave (echoey with long gaps between the repeating sounds). Experience allows you to make more of this but, in each case, you are using aspects of echolocation.

Have you ever dropped a stone or coin down a deep well and listened for the plop? It is especially enjoyable if the well is deep and your object hits the sides on the way down… chink, doof, doof, chink doof-doof, plop. Your object, effectively calls back to you; “Hello-o-o-o; it’s about 10 of your body lengths deep and full of water-orter-rter-ter.” You’ve judged the distance from you to the water by sound-ound-ound. You know the speed of the object you dropped, not in numbers but in mental timing and that gives you an image of the distance to the water below, if it is dark, you may even follow the object down the well with your minds eye and there it is.

As a bat you have a very good ‘sounds-eye’. Now imagine that your stone or coin does not just go away and shout some messages back to you but returns obediently with all the information it has found during its half second journey on an easily readable photograph or a mobile phone app plugged straight into your head. Like a high-speed camera on a high speed yo-yo, your voice came back to you with more information than you sent out. Now imagine that you are firing not one yo-yo but many and they are not yo-yo sized but like steam, blowing out to the world ahead of you and bouncing straight back and displaying an image of a world that is otherwise in darkness like headlights.

Webbed Fingers

Now, a cool feeling spreads up your fingers as the webbing extends from base to finger tip. You have webbed fingers. The control this gives you is quite spectacular. Although you continue to fall you can manipulate the air, or your body at least and change position much more easily. You can sit and you can swim through the air, just not upwards.

That now familiar cool feeling begins again, this time along a line from both your little fingers, along your arms, and down your body to your ankles. A flap of skin quickly grows along this line creating a membranous sheet of skin (a patagium) from wrist to ankle. Suddenly, you can glide, you have the same attributes as a flying squirrel and can move horizontally through the air, borrowing the velocity with which you were falling. You are still descending but now you have control, you are a living parachute and can steer pretty well with jazz-hands. You’re sending out rapid signals. The lake ahead is not appealing but the loosely stacked hay in that old fashioned looking farmyard is. Is it time to hit the hay?

That cool feeling’s back again. This time it extends from your wrist to your shoulder as another skin membrane (your propatagium or antebrachial membrane) forms, giving you more control and lift.

More Bat than Human

It’s dawning on you now that the funny feeling in your behind was not the flatulence that can come with the delirious terror of falling but, in fact your coccyx. It has grown and is only just slowing now as it reaches just beyond the length of your legs. The skin membrane that meets your ankles on the other side has grown similarly on the inside enclosing your ‘tail’ in an almost house-shaped sheet of skin between your legs. It gives you a lot more lift and your descent rate slows some more but it is also a very effective rudder (its your interfemoral (between the thighs) membrane or uropatagium).

If you close your eyes again for a moment, wiggle your coccyx and tense your thighs you are operating the control levers. By moving your tail and legs you can take tight turns even though your general direction is ultimately downwards. From your inner ankles a tough spur has grown out, extending about half way towards the tip of your tail on the trailing edge of the membrane giving you control over this little sail; like the stiffening in a parade-banner or kite. This spur is called a calcar and is one of the features used to identify bat species. You’re more bat than human now, it’s official. But still you’re travelling mostly downwards.

Your inbuilt radar is now picking up not just individual leaves on the trees below but the tiniest of insects upon them. You see them now as an airborne buffets, protein packed tasty morsels floating about just for you. You glide over the landscape now getting ever closer to it and the taller trees are at your height. Soon you’ll have to land and you are aiming for that hayrick, still, but with some trepidation. Your ever faster calls returning ever-more quickly as its form fills the cinema screen in your head. Yikes, here we go.

You put your hands ahead of you now to slow your approach and brace for impact. Eeek, not ready for this. But, your fingers are tingling, pulsing, growing in fact. Your thumb stays as it is but the others, along with your hand-bones, double their length and become much more slender, gracile and flexible, they double their length again, and again until your little finger is almost the length of your body and the webbing has grown too. Your index and middle finger have stayed close together as if mimicking a gun but your little and ring fingers have a large flexible span of skin between them (your dactylopatagium) with an area greater than that of your body and oh! Feel the air. It is as if you have dived into a deep, deep pool of soothing, supportive water but with none of the resistance water gives.

Falling with style

You luxuriate for a moment, feeling the rush of air across your giant hands as you rapidly approach that hayrick and then… you push down. The result is instant lift as the air balloons the webbing between your fingers like an umbrella in a gale. You soar upwards, almost somersaulting but correcting it with delicate movements of your arms and legs, fingers and tail. Then you push down again holding the air in your hands like a climber holds a rockface and up you go again. You push again, and again and again and climb to the sky where, moments before, you thought your last moments would be. Turn tightly, then again in glorious airborne freedom.

You are flying now without a thought of how you do it. You are simply thinking your way along but you become aware of your sonic web. Your sounds are not just projecting in front of you but all around and returning from all directions as well. Close echoes return immediately and distant objects send their messages a little later. You have an orb web of information around you but not on one plain, it’s a sphere of intelligence. Your letters and words change to intensify the signal or cut out unwanted data and your ears swivel in the direction of things you want to know more about.

Time for a snack

The thing you want to know most about at the moment is that fat moth coming in at two o’clock. You fire words at it: Yum…yum… yum..yum..yum, yum, yum yum yumyumyumyum yuuuuuuuuuum and crunch, you flick it with your wing, to your tail and feet and up into your mouth. Mmmm that tastes good. Many bats call through there noses rather than their mouths to make life easier in just this sort of situation. You wouldn’t snack while driving or cycling if you steered with your mouth no more than you would do it blind-folded.

At some point during all this excitement, you have lost most of your mass and are now smaller than the average mouse. Eating in safety and comfort would be nice and you turn to the woods which feel quite homely to your all-seeing ears. An oak stands out as hollow, its echo coming back to you like two coconut shells being struck together, but a softer accompanying echo tells you there are fellow bats in the too. You approach the aperture as rapidly as you dare, extend your thumbs and feet ahead of you, brace for impact and alight, folding your fingers along the length of your forearm, you quickly walk on knuckles and feet into the safety of the hollow tree; with moth in mouth.

It is not unlike entering a pub or a party. Everyone is chatting and eating, preening or dozing off. Youngsters squabble in the play area whilst some are nursed by their mothers. You nip off the moth wings just as you might pull the cork from a bottle with your teeth. They spiral down to the floor. The most noticeable difference from a pub (beside morphological ones of course) is that everyone is hanging upside down. You see me in the crowd.

“How’re ya hangin’? How was your flight, er, trip.”

“That was amazing, this is amazing.”

“How do you like being a bat?”

“The world feels so rich, sound feels so lush and colourful, the air is like pillows and stepping stones.”

“Will you go back?”

“Who’d be a human after being a bat?”

“Ha, thumbs up to that.”

Bats and You

Of course, I can’t fully imagine a bat’s umwelt, but that’s my best attempt. Bats are known to be highly intelligent and sociable and to see the world or hear it, differently to us.

I have no desire to interfere with bats but do like to watch them and love that they are on this world in many forms. No bats, have really faired well with humans, we have put them all in danger. You can help reverse what we’ve done.

Bats in our world

We need to remember that our homes, cobbled together from quarried materials, felled timber and oil products, are potentially homes for bats too and are built on their ancient hunting grounds. We once lived in trees and in caves and shared our space with bats but nowadays they are often seen as intruders. Hermetically sealed roofs and walls may be good for energy saving and the environment but offer no home for bats so allowances and more have to be made to give bats homes.

For us, if we want bats to survive, it is a time for uncompromising compromises, environment and bats means we can’t have it all, we must give something, some things, back to the natural world. As street parking becomes harder in this world of cars (we’re becoming daleks!) many are building or extending parking spaces in their gardens. I’ve done it. Individually the difference is small but regionally, nationally, in many ways, bat hunting and roosting habitat is being nibbled away along with the nurturing Umwelts of their insect prey.

Insecticides, herbicides, sanitization, land drainage, insect repellent, pet flea treatment, block paving, concreting, tarmacking, draft-proofing, sealing off wells and caves, veterinary treatment of farm livestock (e.g. Avermectins) and the removal of dead farm animals for burying or incineration, tree diseases, poor choices of ornamental and crop plants, over-intensive management of parks, gardens and roadside verges, filling in of ponds and culverting of waterways, street lighting and other light pollution, noise pollution all these things effect the lives of bats and/or their crucial insect prey. Fewer insects, means fewer bats, some species need midges, others need moths and others beetles.

The sound of silence

The above, however, is just a list of human things that may or may not have affected bats near you or far away or, you hope, not at all. As a bat, you might see it differently. I sometimes wake up in the night and I hear a hum. It’s always there but is not so noticeable in the day. In trying to find out what it was I turned off the mains electricity but failed to stop the hum. It seems to be coming from the windows and drains; pumps, distribution boards and motors, in some cases, probably miles away.

I have also spent a lot of time waiting in the dark for badgers and foxes to show up. It can be quite magical listening to voices and vehicle noises gradually depleting until, eventually, there is almost no sound at all. It is sometime after that, that I hear the rustle, scratching or sniffing of the animal I want to see. They are not just waiting for dark, they are waiting for quiet, when they can hear danger, prey and social opportunities.

At the opposite end of the day, I have settled down near badger setts and fox earths at 5am and awaited their return. It is a very different feeling hearing the city outside a park waking up. It’s nice when you are in it and the bakery opens but, as a being who lives on the intricacies of sound, the quiet nights get shorter by the day as the noise of humanity fills them up.

As a bat lover, Halloween became my favourite celebration. It snuggles in nicely with bonfire night which gets us outdoors as the colder weather closes in. I loved fireworks and love them still but not everyone does. Our dog is terrified of them and many dogs and other pets I know runaway from safety, not towards it, in their terrified state. With their even more sensitive ears, I wonder if bats feel the same, but without the comfort of domestication, about these and many other man-made noises… aircraft, strimmers, chainsaws (used by woodland conservationists!), electric pylons and communications masts, maybe even bat detectors, do we really know? I’ve got a bat feeling about this!

Getting brighter

Whilst the world has become ever noisier, it has become ever brighter too. Streetlights have extended out of towns into villages via country highways. It is difficult to find a place in Britain now, where you cannot see artificial light. Some bats avoid it.

You emerge from your roost in the old ash tree. You don’t want to but you must as it has blown down in the wind, another victim of ash-dieback. Roosts are harder to find these days. Giant elms are long gone and suitable trees are less common near suitable hunting grounds. You scan the town, it is so bright, you would only live there in desperation and the noise, the roads, the shops, the factories and the pylons and communications masts all make noise that is interfering with your sonar.

Flying past many houses, some where bats used to live but now sealed up with upvc and mastic sealant that keeps out, draughts, drips and bats. You give up looking for a new home for a moment, you are hungry. Your favourite food, beetles, are harder to find these days. Most farm livestock have been treated with avermectins , sterilising their dung and the ground it lies on (like someone sprayed the contents of your fridge with poison). Crops are treated or intensively managed too and you have to search longer, further and harder to find enough to sustain you.

The insects you manage to find are sub-optimal, resistant to chemicals and have a nasty taste which you know isn’t doing you any good. You find a hole in an old roof and wriggle in. The space is fine, the temperature and humidity feel right but you can barely breathe… timber treatment; many forms are deadly to bats. There is nowhere you can find to roost, dawn is breaking and you take refuge from the rain on a window frame.

Autumn is coming on and you must build up your body weight for the winter and then move to a hibernaculum; a stable winter roost. Your worries are more immediate now though – a bit like falling without wings. A cat saw you land on the window frame and is stalking you. The owls haven’t quite gone to roost and the kestrel will soon be awake. You cannot hear your family and don’t know where they are. It’s too noisy, you can’t hear anything in your world where hearing is everything. This is as true for bat species and families, as it is for individuals.

How can we help bats?

As a human you can help. You could join a bat conservation group or put up bat boxes, garden in a bat friendly way or record bats in your area to provide data for conservation efforts and encourage anyone you know to do the same.

As I understand it, there are 17 bat species found in Britain + some occasional species. The 17th (Greater Mouse-eared Bat) was down to a single known individual when I last checked but had formerly been declared extinct. Most other species have suffered drastic declines. I never did grow up to be a bat expert (I spanned out!), my bat identification isn’t great and it is difficult or impossible to confidently identify flying bats with no bat detector but, for my own improvement, I have made these comparative outline sketches of the more common British bats. I hope this helps you empathise with bats and know them better. Perhaps Santa will bring you a bat-box to share your home with new friends. Don’t ever be un-batty; thumbs up for bats.

Spotting Bats

Spotting bats flitting around on a Summer evening is one of life’s great pleasures! It can often be difficult identify which bat your seeing.

I’ve created this size chart/guide of the bat species found in Britain.

You can download it by clicking on the image. The outlines are drawn to scale, I hope you find it useful.

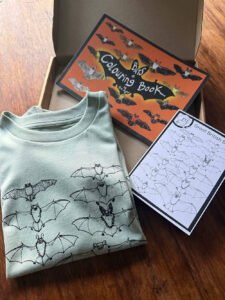

Bat Products

As you may have now realised I’m a little obsessed with bats, you can find links to our bat products below.

I hope you love bats as much as we do!