An introduction to echinoderms and their weird and wonderful lives.

Have you ever lost touch with a relative? It’s a rhetorical question really because you and I are related but our ancestors lost touch hundreds or even thousands of years ago. It is, in biological terms, meant to happen, we are made both to disperse and stay put in equal-ish numbers to ensure our survival.

Protostomes are them and Deuterostomes R us

About 600 million years ago, we, the Deuterstomes, parted company with the ancestors of worms, insects, spiders, lobsters and snails. It may have been a simple mutation within a population, but it is likely that it was a mutation with some physical boundary. Such as a rising mountain chain or widening ocean that separated us from the Protostomes. Only for us to meet again many generations later.

This separation would allow us to become different enough to be incapable of interbreeding and to forevermore follow different evolutionary paths. Who are, or were, these two groups whose names I don’t expect you to remember? I struggle to remember the names of much closer relatives than this. One thing worth remembering puts us in our place, in embryological terms (but please remember I’m a layman on this subject) the protostomes are defined and named by the fact that the mouth develops first; lucky them. For us the deuterostomes it is the opposite. We come into the world bum first. No wonder we’re so confused.

The arms race

It seems that, at around about this time we animals all stopped minding our own business and began eating each other and defending ourselves against those who might eat us. Minding our own business is a relative term; we’d been eating our fellow beings, the plants and others, for quite some time! This new more vicious occupation meant bodies getting bigger and the development of claws, spines and armour plating, along with high-definition eyes. You probably know this already, but I like the drama of it. The us, the Deuterostomes is not mammals, or even birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish. It is all their ancestors as a single-ish common ancestor, along with other notable ancestors in a sort of microscopic, low detail, pantomime horse. It was perhaps more of a pantomime grub than a horse though.

Meet Granny Echi

This humble creature, described by Richard Dawkins as our 280 million greats-grandparent, comprised our ancestors, the ancestors of acorn worms, pterobranches and Xenoturbellids (please don’t try to remember the names right now it will spoil the flow) and, most importantly for this article, the echinoderms. I want you to visit the echinoderms with me. They are our long-lost relatives, our closest relatives among the invertebrates. I particularly want to share the ones we are most likely to see in Britain and Europe. In other words, the ones I’ve actually met myself.

A tale of two grubs

It was another 20 million years or so before the two little grubs that were us and the echinoderms parted company; and how we blossomed. The grubs on our side of the family diversified into rays and sharks, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Until we reached the present pinnacle of evolution – Bats. Hang on, who’s telling this story?

Anyway, before we could become bats, or humans or even jawless fish, we went through our sea squirt phase, while our echinoderm siblings became…. beautiful sea lilies, starfish, brittlestars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers. Sea cucumbers, though lovely to me, are, to many, the embarrassing relative who always turns up at get togethers. Someone has to be at the bottom of the stack but, strangely, not in our family. Actually, I may just have realised something life-changing there so, moving quickly along I want to take you through a series of meetings.

When’s the top the bottom?

Somewhere along the line, after we parted, echinoderms developed radial symmetry, which defines them as a group (a phylum- our phylum is Chordata and theirs is Echinodermata). Our pattern loving eyes and brains find their radial symmetry beautiful, in most cases, even though we are bilaterally symmetrical ourselves. What this means is that we have a front end, a back end and sides just as fish and worms do. But most echinoderms have no front or sides just a top and a bottom. The mouth is usually on the bottom which is known as the oral side and… you’ll like this; the bottom, to put it politely, is on the top, which is known as the aboral side.

The embarrassing sea cucumber, though still radially symmetrical inside is elongated and so looks more like us, and worms to whom neither of us are closely related. I hope you are keeping up. The radial body plan, like a wheel is divided into five segments which show up in the five arms of most starfish.

Spiny or feathery?

Echinoderm means spiny skin but it is a bit misleading as they don’t all have spines and some, have feathers. I am going to start with feathers because it is the one that’s missing from the list I can give as actual experiences. Sea lily’s feathers are not quite the same as bird feathers and sea lilies don’t fly, or even swim (with an exception) in their adult phase. But they are feathery for the purpose of filtering food out of the water. They are more properly, or completely, called crinoids in order to include forms known as feather stars. I would love to see one alive but I have not; not in the wild anyway.

The only British crinoid is the Feather Star (Antedon bifida) first described for science by the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant, after whom the lovely Pennant’s swimming crab is named. Feather stars are out there from the low tide mark to 200metres deep. They are the exception among crinoids because they are not stuck to the seabed by a stalk and they can actually swim. I am a bit peeved to say that I’ve never found one.

Sea Lilies

What I have found though, and what you can find too without leaving the country or getting wet, is their prehistoric but less mobile relatives. Living Sea lilies are now confined mostly to very deep water, they were thought to be extinct until they were discovered alive (for the first time by humanity and not just western scientists) in 1755 (albeit by pesky western scientists) in deep water off Martinique. But they were once common in the shallows and they, or more commonly the little discs that made up their stalks, are found in fossils over many parts of Britain.

A Visit to Dudley

Often, they can be seen in the stones used for buildings without any need to go searching in quarries and escarpments. The town of Dudley is a geological treasure trove and the castle wall and the castle itself (which stand within the grounds of Dudley Zoo or vice-versa) comprises Silurian rocks (420 million years old – by which time we were distinctly fish-like or perhaps tadpolesque) with crinoid segments in it. The town museum displays some of the best examples of these mysterious plant-like creatures more closely related to us than octopus or crab.

A good ten-minute walk out of town will get you to the Wrens Nest National Nature Reserve. This was the first geological nature reserve in Britain and is worth the trip just to see the rippled seabed. It’s locked in time with crinoid segments and other animal parts lying within the ripples, as if the tide receded just a few minutes ago. But the seabed is tilted at a ridiculous angle by the movement of the Earth’s crust.

Crinoids also feature strongly in much younger beds at the National Stone Centre, from a time when we might answer if you shouted “Sally Mander!!”

Unchanged

I suppose that is the most stunning thing about sea lilies. Time, from the arrival of animals, is divided by scientists into three great eras. The Cenozoic is the current time going all the way back to the extinction of the dinosaurs, ammonites and others 65 million years ago. This is preceded by the Mesozoic Era when dinosaurs and other reptiles dominate the fossil record, which takes us back to 245 million years ago. This was a time when a huge extinction took place which wiped out more than 90% of all living species.

So, the preceding Palaeozoic Era, and especially its early periods has fossils of species and families that look nothing like those of today. Trilobites, ammonites, sea scorpions, graptolites, brachiopods, even the corals look different and odd-looking fish are late arrivals. But the sea lilies and some other echinoderms are easily recognisable, seemingly unchanged to this day as if nothing Earth or Space can throw at them is enough to wipe them out or make them need to adapt like almost all others have.

Meeting living echinoderms

I guess my first meeting with an echinoderm was in Filey on the coast of Yorkshire. They were not common there but common starfish used to turn up occasionally especially at low tide under the bladder wrack and serrated wrack fronds that are such fun to turn over. You never know what you will find.

Starstruck

Common Starfish are voracious predators and must be related to me because they have an insatiable appetite for mussels. They use hydraulic power, another unique echinoderm attribute, through their tubular feet, to exert irresistible, force. Which eventually tires the mollusc thus allowing, and please remember the beauty of the starfish before I say this; allowing the starfish to distend its inside out stomach into the mussel’s safe haven and digest it alive!

Horror movies pinch all sorts of ideas from nature but I’ve never seen someone screaming in a room, as a big acid exuding stomach flobbers in through a window. Can you imagine an echinoderm superhero with immense strength due to their hydraulic power, combined with invincibility due to their covering of pedicellariae?

Sorry about the big word but it’s a good’un as they say in Filey. Imagine that your entire skin is covered with bristles arranged like the bristles on a tooth brush, a bit like a buzz-cut hair style, but all over you. Now imagine that each bristle is tipped with either a knife or a pincer so that nothing can settle on your skin. I pity the masseur myself. Starfish girl, or boy, may run into trouble against a samurai who could chop them to bits with their sword but there’s a good likelihood that the bits will grow into new starfish, as long as there is a bit of the central body attached.

Of course, starfish girl, or boy doesn’t need a head. The mouth is at the centre of that beautiful radial body whilst the bum, if you are wondering, is on the opposite side, usually pointing upwards as if it is mooning us. The eyes, or light sensors really, are on the tips of each arm.

Urchin

My first urchin, an edible urchin (Echinus esculentus), was also in Filey. My Grandmother scrounged a live animal off a fisherman and, aged 12, I watched it for hours in a washing up bowl. It extended its tube feet and moved a bit but never off the bottom of the bowl. It was probably doomed from residual chemicals in the bowl and the shock of being out of the water for the best part of an hour. But I always felt guilty for being the one who watched it die and failing to get it back to sea in time. It was an impressive pink and purple globe a good 16 centimetres in diameter.

I scrounged another one from fishermen in St Ives when I was 13. I had taken a bucket to put it in to keep it alive so I could photograph it. My mode of transport was an inflatable dinghy and on my return journey I was harassed by 4 yobbos in two larger dinghies who thought it hilarious that I had brought a bucket with me in case I was sea-sick. It is quite funny looking back now but oi wuz worried fur moi urchin; that they’d steal it see. I had a secret weapon aboard. A huge dead spider crab which I was going to use to puncture their boats if they tried to board me. The eventuality would probably have been me suffering some part of the spider crab stuffed up my backside but it seemed like a good plan at the time.

An introduction to sea urchins

Urchins, properly called sea urchins because the ‘true urchin’ is the hedgehog, are worth a closer look. They possess tube feet just like a starfish and use them to walk around in just the same way. Imagine a starfish which has curled the tips of all it arms upwards to meet each other above the centre to form a cage. With each arm then zipping up onto the one beside it, to create a ball covered in extendable suction feet. Et voila, there’s your urchin. Their spines can each be moved independently, seemingly, wilfully which is pretty clever. I am a higher vertebrate (a name we gave ourselves) and a supposedly intelligent being, but no matter how hard I try I cannot move a single hair independently; I’m trying now; nope, it’s just not happening.

Urchins are clever. Unlike starfish they are mostly vegetarian. Well, vegetarianish, they’ll eat bryozoans which masquerade as plants. They would be caught out by passport officials if they tried to sneak through customs as a plant. Simply because their other name is moss animal. Urchins also eat barnacles and anything else not quick enough to get away. It must be horrible watching, smelling, feeling or hearing the urchin coming along towards you. Something plants have got used to, but still produce spines, stings and nasty chemicals to stop it. The urchin’s jaw system from the outside is made up of five beaks. Which come together like an origami puzzle or a fictional spaceship door.

Aristotles Lantern

They are connected to a complex structure known as Aristotle’s lantern which operates them. Either his lantern was very bright or Aristotle was very small! The edible urchin is the UK’s largest and easy to identify. But there are other smaller urchins that I often need an I.D. guide to identify. I used to consider them to be rare finds, rock pooling or snorkelling (in Cornwall and Wales) until I visited the west coast of Scotland. The smaller species are more likely to be in rock pools and so are more accessible.

One algae grazer, rare in Britain, deserves a mention for me.

Danger, Keep out, poisonous sea urchins

The same year, in fact, the same school holiday period as the boat bucket incident; I went to Italy with my dad and sister. Dad and Mum had separated in the New Year and an unexpected benefit was two holidays. We stayed at a ‘Club Med’ resort, Palinuro, which was good for lizard hunting but otherwise, a nanny state! We were penned in and signs warned us not to go near the sea. If we could get to it, because of the poisonous urchins. I was, of course, intrigued. I eventually found a way through a gate left open in the chain-link fence. And set eyes on the little sea devils. They were dark and looked like negatives of stars, blast holes in the rock to a dark underworld. They were not to be touched! But they were fascinating.

All aboard with Captain Kirk… or Cousteau

Among my favourite memories is sitting with my family watching Captain Kirk and the crew of the Enterprise head into space, and Captain Cousteau and the crew of the Calypso head into the deep. My Dad had his own armchair. In which we would often snuggle or playfight and it faced the TV screen just like Captain Kirk’s. He was Kirk and I was whoever his most loyal and able crew member happened to be at the time. Cousteau was something else, a hyperactive Merman, fascinating and almost unreal compared to the almost more believable Star Trek.

The Boat Trip

We went on a boat trip with lots of other rowdy holiday makers. I think Bill Bryson would describe them as pot-bellied urbanites. The boat moored in a cove and the skipper invited people to grab a snorkel and mask and “a-jump-in” so we could swim, in a group into a cave. I had never snorkelled before but had dearly wanted to. Dad, usually keen to do anything, was not so quick to a-jump-in to the action as he normally was and people were plunging over the side. I grabbed a mask and plunged in too and waited for dad to follow. In he came but surfaced gagging and climbed back into the boat. Still gagging and coughing he muttered that his snorkel had leaked.

The pot-bellied urbanites and tour leader had not waited. By now the tightly clustered splashing rabble, my sister among them, were disappearing into the cave entrance in the cliff side. It was like the last scene of the pied piper of Hamlyn but set in water. They were too far away for me to safely catch up and I was worried about Dad. He’d stopped spluttering now, but was showing no inclination to go back into the water. Had I found… a weakness in this invincible being? Just my luck, I thought Captain Kirk could be Captain Cousteau too, but perhaps Cousteau had shown us too much. And, to consolidate doubts about maritime fun, Jaws had screened the year before.

However, the echoing of the crowd resounded from the cave, whilst out here there was the delightful sound of lapping water. Perhaps I was better off where I was? The water was deep, too deep to see the bottom, and there was a strong swell. I had not been out of my depth in the sea for this long (about 2 minutes) before. Bobbing about, I had spluttered a commentary to Dad about the group getting ever more distant and then disappearing. Now what?

In Deep Water

Many of us have to experience this moment I guess, when our Dads, our heroes, our role models, falter or fail. But I suspect it was an act. He was only pretending to have breathed in water and not because he was afraid of jaws or poisonous urchins in caves, but because he was being a hero. Neptune had appeared to him, put a gently restraining hand on his chest and said, in a very deep bubbly voice;

“Let the boy go Clive, let him swim, let him earn his trident.”

“Just swim about here,” he said, “I need to recover on the boat.” And then I did it. Treading water vigorously, stamping down one foot and then the other, I lifted my arms to the mask perched on my head and pulled it down over my face. I put the snorkel in my mouth and my face into the water. The first feeling was panic as a new world and new environment burst into view. To breathe, seemed like the craziest thing to attempt with my face in the water, and I was so used to holding my breath that I had to force myself to breath. First, a little sip from the snorkel, then a huge gasp and then an attempt at normal breathing. My breaths were rapid and ridiculously loud. I lifted my head, back to reality.

I’m snorkelling!

No, it was OK; the sky was still there, the boat, Dad. I put my face back in the water and started to swim. It is so much easier to swim face down and especially with a buoyant bubble attached to you face. I felt as if I had just discovered my super-power and taken flight. The deep blue seemed endless. I still could not see the seabed, but was fascinated by my arms, feet and the behaviour of bubbles. Raising my head from the water, I remembered what this blog is about, and something caught my eye.

A Living Merman?

There was someone in the water beside the cliff, interacting with the rock face. I had been unaware of it happening but a crew member had entered the water and not gone with the group. He grabbed something off the cliff and then ducked his head into the water and disappeared. As shiny black flippers rose up like a whale’s tail, or a merman’s and he was gone. He was gone so long that I thought I had imagined it and I swam towards the spot where I last saw him. I reached the cliff and looked down its escarpment into the deep. There he was, I could see his bubbles more easily than him. .

He held a hessian sack in his hand, that looked like a full sack of coal. But it wafted freely in the swell giving him the appearance of both immense strength and weightlessness. He had a sheath on his belt (not his leg as Cousteau would). Its normal occupant was in his gloved hand. I saw now what he was doing for sure. He was collecting urchins. Some could be picked straight off the rocks, others he winkled out of their rocky crevices into the sack using his knife.

His mask lent him anonymity, a distance that made him seem inaccessible like a monk in hood or like Darth Vader. He glanced upwards in my direction; all I saw was the reflection of his mirror-like mask.

A 30-minute role model

He picked up an urchin, continuing his occupation I thought, but turned again and kicked his fins, seemingly once, and glided towards me as weightless as a ghost. Now I saw his eyes and he held my gaze. There’s no smiling with a snorkel in and he looked deadly serious. But I could tell that his intention was to interact, to show me something. The gleaming, glinting knife was back in its sheath though I had not seen him do it and he held the urchin in front of my face.

Water makes things look about a third bigger and a third closer to our eyes. So, rather than looking other worldly, it looked super-real, almost as if it’s being extended into me in that instant or being projected around me like an omni-theatre. It was predominantly a dark purple, it was a purple urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) after all. But was close to black, fading into elements of green and brown, and it remains one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen held in a human hand. I had never seen an underwater cliff face before. There were fish and weeds and a whole new world beckoning as we bobbed up and down but, for once, I was more interested in the person. This was a naturalist, a key-holder to the world I wanted to be in.

Back to the boat

He beckoned me to follow and we swam back to the boat. Kicking his fins very slowly to tread water (while my little feet were going back and forth like bee’s wings). He reached up and hung the sack on a cleat, took off his gloves and threw them aboard. Then, pulling the mask to the top of his head, he grabbed a handrail of the boat with extended arms and pulled himself effortlessly out like a gymnast on the bars.

He then lifted me effortlessly out of the water too, planted me on the deck and gestured to a seat.

Were we aboard the Calypso?

Dad was probably talking to me, asking me how it was, but I was fixated on this guy. I wanted to become like him. Actually, now I think about it, Dad was talking to a woman passenger who had also decided to stay behind. Hmmmm, his mermaid was on board all the time perhaps. Sometimes you only realise what’s going on when you write it down. His heroic honour held true and he still clasped his own metaphorical trident as he does to this day.

My merman guy leaned over the side and grabbed the sack of urchins. Its bottom had still been in the water and glistening droplets fell from it onto the deck. Spines protruded from the hessian sacking but somehow he had managed not to prick himself on the ‘deadly menaces’.

Comparing urchins to Boris Johnson

He was older than me, probably late teens to early twenties and was the youngest of the crew. In the same way that I was the youngest of the passengers; we shared youth and a passion for nature. What we did not share was language. He put his spread fingers on his chest and told me his name, I don’t remember that now but want to say… Marcus. I told him my name and we shook hands. He raised a finger to indicate he was about to show me something. Sitting in front of me, he reached behind him grabbing a small pair of scissors from the boat’s ‘dashboard’. He opened the sack and made a magician-like gesture with the hand that he was clearly about to put in there to indicate delicate handling.

“Gentle.” He said.

As if drawing a rabbit from a hat he brought out an urchin. It was the size of the palm of his hand, gently resting in a cage formed by his fingers. He held it up to me and smiled.

“Oorshin?” he said with the hint of a question at the end.

“Urchin,” I responded, “sea urchin, yes?”

It was not how it looked underwater, even in his hand. The lustre was distinctly lessened and the spines were dishevelled, like Boris Johnson’s hair. It was not coping out of its element. Perhaps Boris Johnson belongs in water and is out of his element! A sequel to The Kraken Wakes as urchin headed aliens gradually take over the top jobs in the World’s nations. Hmmm.

“You taste,” he said, “I show”. This is the merman speaking not Boris Johnson, who has no place in this delightful little story.

He gesticulated to the cliff.

“Here, clean,” he said, “safe. There,” he pointed to our holiday park about a mile across the bay, “dirty,” he finished; “Dirty for food”. I had that feeling too, but it did have ocellated lizards and glow worms so I loved it.

A Taste of Echinoderm

He took the scissors and rolled the now unfortunate urchin onto the palm of his hand so it was upside down. Pointing to the soft tissue that surrounds the mouth, the buccal mass, he drove the scissors in. He then cut into the shell and round in a circle to take out the base of the animal, which I very much hope was now dead. The interior was as symmetrical as the exterior with five bright orange strips radiating from the centre. He cast the base of the poor beast into the water. It wobbled its way down into the depths, leaving a small grey cloud of ‘urchin-blood’ behind at the surface. I wanted to watch it sink, watch the fishes attack it but, once again, the man and not the scene, were more interesting.

He took the knife from his belt and slipped the blade under one of the orange strips, separating it from the shell. Known as a test as in testudo (tortoise) and a form of mobile shelter used by roman soldiers when attacked from above. Which name came first? I don’t know.

He offered the blade to me and slid the little orange organ into my open palm. He then slid the knife back into the test and brought out another. Which he slid, from above, into his mouth, like a classical scene of luxury grape eating. Raw food, better still, raw echinoderm, I jumped into this world with both feet and licked the morsel off my hand. Mmmmmmm. It was delicious. It tasted of the sea, I became a smile as a new world washed over me. I felt I became, from that moment, a part of the sea, but in truth, I’m just a monkey, and the sea became part of me, yep, I’m a sea monkey.

Moving on…

Where is this going? I’m supposed to be celebrating British echinoderms and I’m bobbing about on a boat off the Italian coast with a seasonal tour assistant eating orange gonads off a dirty knife.

Yeah, the orange strips are the genitals, called roe in cookbooks, and the best ones are, I believe, egg-filled rather than the alternative, but let’s not go there. Most English-speaking cookbooks don’t.

The dissected, let’s say filleted, urchin in his hand was now a bowl, with three more portions of the delicacy within. He put down the bowl, reached behind him and grabbed a small towel. Placing the towel in my hand, he put an urchin upon it, and took another urchin out of the sack which he placed on the towel. He then handed the scissors to me. Ooooooooooh! Game On!

“Please, careful,” he advised “Spike, hurt, stay in.” He tapped his own hand to show me.

A risk of Salmonella!

Back at home, I was already dabbling in taxidermy, so cutting open an urchin was no big-deal. In went the scissors, off came the ‘tureen-lid’ and there was the bowl of Ricci di mare. With a flavour like very salty creamy eggs, it is apparently, highly nutritious containing fatty acids, proteins, iron, and phosphorus and has one of the highest iodine contents of any food. The merman didn’t explain all this, it was the swimming, foraging, born to be wild completely absorbed in nature in a Tarzanesque way that I loved.

Thank you merman and thank you urchins. As you can imagine, the conversation behind me, on the boat has stopped and my dad is wondering whether to intervene. He didn’t and we sat gesticulating to things and saying their names in our own language whilst eating about three urchins each. Hang-on, come to think of it, the conversation carried on behind me all the time, dad never looked up and was never thinking of intervening. I’ve just read a website that tells of the risks of eating raw urchins: salmonella, Hepatitis A and E and… Cholera being among them! Perhaps sauté those gonads in a little oil first? Gosh, I have eaten a lot of them since then.

Memorable moments

What a half-hour that was in my life. I snorkelled for the first time, ate raw seafood for the first time that I had prepared myself and had a fabulously close experience with an echinoderm, a rare phylum in land-locked Nottinghamshire. I hope that merman, now in his sixties, is still doing, demonstrating and enjoying exactly that, I would, if I were him. Very few others were interested at the time. The urchins were seen like wasps… dangerous and yucky.

We looked up at each other from our echinoderm bowls as an echoy sound reached our ears at the same time.

“It iza the pot-a-bellied oorbanites, retoorning like-a- di sheep in di water,” he said gesticulating with his thumb over his shoulder.

Actually, he didn’t do that, but I thought it and was so glad, as I am today, of that serendipitous abandonment. The merman simply put his index finger to his lips, winked, closed the bag of urchins and went back to his duties preparing the boat to move on.

Back to Poison Beach

I later went back to that gate to the beach with the sign on it saying something like; Ingresso vietato, ricci velenosi and bearing a silhouette picture of a bare foot and an urchin. I snuck out and soon had an urchin spine in my big toe, another in the side of my foot and one in my finger. My stomach too was full of urchin despite the warning, what was I thinking! Perhaps I pricked my finger on an enchanted urchin and became the super-hero, Echinoderm-Boy. The pain of the spines was sharp at first but quickly faded away, a bit like a nettle sting. It was the following day when it really started to hurt and in-absentia, the urchin’s superpower had my attention.

Crumbling spines

The spines cannot be pulled or squeezed out like most thorns, they crumble. The only way to get deep ones out is to dig down to them, wait for them to sort of dissolve over an unbearable period of time or admit what you have done and go to a medical centre. You’ll guess which I did. By the fact that I know they crumble. I advise you to seek medical attention of course.

Cucumbers

Let’s stay south of Britain for just for a moment for it was here, that I first encountered sea cucumbers. British ones you are likely to find are so small and un-assuming that the magic is easily missed but there are stonking great big ones out there and the cotton spinner (Holothuria forskali) is one.

One day on a beach in sunny Spain

On holiday in Fuenterrabia on the Spanish Atlantic coast, aged about 6, I pulled what looked like a giant spiny sausage out of a rock pool. Most people at the time would have thought it looked a bit too much like poo to pick it up, put it in their bucket and take it to show their parents but I felt compelled to do so. Yes… there may well be something wrong with me, but I’ve decided it is cute or too exciting to resist.

Anyway, while I was lifting it from the bucket and my folks were observing me take what looked to be a large piece of human poo out of that bucket with my fingers to show them. Whilst a wave of panic and nausea spread over them. How do you rescue your child from something you are too revolted by to touch or even look at and which other parts of him has he touched with those hands and that, that thing. Yes, while that was happening, that thing squirted water, in a powerful jet much like, well, wee-wee as I turned it to face them.

Echinoderm Superpower

They scattered. It is quite empowering to hold a weeing poo, and, if you have insecurity issues, you should try it. It was of course, a cotton spinner, a large sea-cucumber of Europe and the only member of the Holothuriidae to be found in British coastal waters, although it is pretty rare here. On the continent, especially in the Mediterranean they can be abundant.

Their defence, along with squirting water is to eject sticky white threads (that’s where the cotton spinnin’ name comes from) from the anus, well where else really? To entangle predators, fishermen, schoolboys, and their parents. It’s an Anus horriblis, hee, hee. Luckily, we got off lightly but it was never forgotten. What a fabulous super-power for our echinoderm boy or girl; to spurt water or sticky stuff from your bum that entangles your enemies.

British Sea Gherkins

Sea cucumbers are a world of fascination in their own right with over 1000 species worldwide. They come in a variety of pretty indescribable shapes and every colour combination imaginable. There are, as far as I can tell, about 19 species in British waters, of which I have found just two. Cucumaria frondosa which has no common name but has shown up on a snorkelling excursion on the west coast of Scotland and, washed up on our local Welsh beach after a storm. Also the delightfully named Sea Gherkin (Pawsonia saxicola). It lives in holes created by other species and protrudes sticky appendages, encircling its head, like fingers out into the water. Small floating plants and animals get stuck on the fingers which are then bent back to the mouth and ‘licked’ clean, yum.

Cucumber World

Please don’t underestimate the sea cucumbers or holothurians; I’ll quote my Purnells Encyclopaedia of Animal Life.

“One species, Galatheathuria aspera is flattened and swims freely in the sea. Another Pelgothuria natatrix is shaped like an octopus with a dozen arms and probably swims near the surface. At the other extreme is the extraordinary deep-sea Scotopanes globosa with a rounded, oval body, almost like a giant tick, and with two pairs of bent ‘fingers’, one pair pointing forwards, the other backwards.”

Purnells Encyclopaedia of Animal Life.

To help them move along, as well as perform other functions, some sea cucumbers have anchors (actual anchors) made of calcium compounds. These, often microscopic, structures, are often the only way to identify species. They have delightful shapes with delightful names such as tables, discs, wheels, rods and baskets, as well as anchors.

Urchins Again

And back to the urchins. I have not found the purple species, so common in ‘The Med’ here in Britain. I have found green sea urchins of various sizes, but have not identified for sure, which of the variably coloured half dozen or so species of smaller urchin, but suspect they are mostly Psammechinus miliaris and Echinocyamus pusillus. It seems I cannot identify them without disturbing them. I am often happy enough to leave animals to live in peace, anonymously.

Dollars, potatoes and hearts with bows and sterns

Spatang! On now to the Spatangidae. My first spatangid experience was on Hayle Towans in Cornwall. I was very excited to have found a ‘sand dollar’ a species I had only seen in books.

Looking it up, my sand dollar was described as a ‘sea potato’.

If you don’t snorkel or rock pool much, but you do like large sandy beaches, the sea potato (Echinocardium cordatum) is the echinoderm that you are most likely to come across. It is another British marine species first described by Thomas Pennant. Its delicate tests come washing in, often complete in spite of their fragility. I find it miraculous that they can roll in to shore, undamaged, often all the way up to the high tide mark on a stormy surf. But try taking one home in your pocket or a bag and you are likely to end up with fragments or dust.

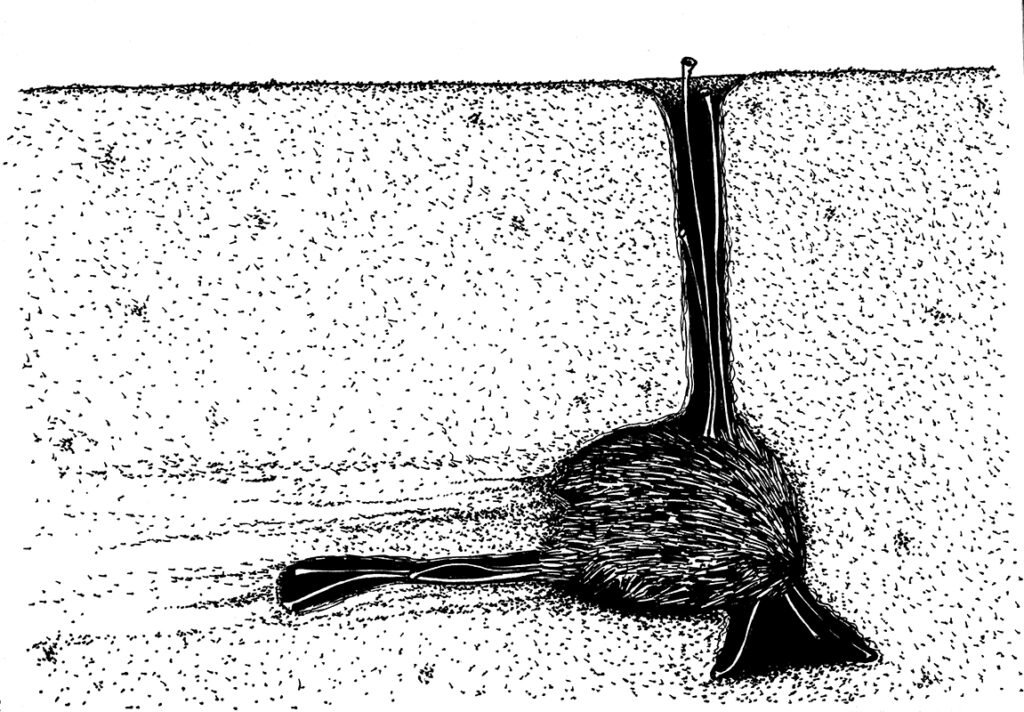

The Burrowers

Spatangids like to live anonymously too. I must have found several thousand tests ,but never a live one and very few that looked alive. If you are walking on a large sandy beach at low tide, it is highly likely that sea potatoes dwell beneath your feet. They like the lower intertidal area. They are burrowers and, in life are covered with spines and have lost, or supressed, their radial symmetry for a more ship-shaped appearance. Well, they have a bow and a stern but look a lot like a potato that is evolving to be a dodgem car, with a strong hint of hedgehog. Even if you find one with spines intact, you are usually not experiencing the complete animal. Those tubular feet so obvious on living starfish and sea urchins are specially adapted in Spatangids. My handbook of marine fauna pulls no punches:

“This family is characterised by ciliated spines (the sub-anal fasciole) situated below the anus and enclosing a group of ‘sanitary-drain-building’ tube feet.”

handbook of marine fauna

An Unusual Lifestyle

If you look at the beautiful symmetry and texture of a sea potato, the prettily arranged pimples (there’s a compliment) tell you where the soft golden-yellow spines once were. The sea potato, in life, is in control of these spines. Using them to dig and guide itself through the sand. Almost like a mole, except without the powerful digging feet and only its hair to do the work. Now there is a superpower. If I could swim through the earth using only my hair, it would leave my hands free for other things. Like holding a book or an ice cream cone perhaps.

It uses its tubes behind it to vent out waste material into a cavity or burrow that it leaves in its wake. Maintaining a shaft to the sand surface with more tube feet. In order to breathe and keep in touch with how deep it is. It’s a bit like snorkelling through sand underwater. Too deep and it could suffocate, too shallow and it could be exposed and washed ashore by the waves.

The feet, also bring down food, which is usually above rather than ahead. I don’t think I’d like food in my snorkel. They maintain the snorkel/feeding shaft by lining it with mucous. I used to do that when digging in the sand with a runny nose but without the efficiency of the sea potato. Research has shown that they are often gregarious. How do they know where each other is? Could it be chemoreceptors in those tube feet? Another super-power perhaps? I sometimes, very very rarely of course, have smelly feet. But it could be incredibly useful to have smelling feet. Not both though and you wouldn’t want to step in anything unsavoury. Moving on… The perforations in a sea potato test, and any urchin test for that matter, show where the tubular feet protrude through the shell into the outside world from the soft being within.

There are five other spatangids living around Britain so look out for them. They are collectively called heart urchins (the sea potato can also be called common heart urchin) and the purple heart urchin is probably the next most common along with Brissopsis lyrifera.

Back to the Stars

The common starfish is abundant and unless you enter the water or go rummaging, is the one you are most likely to see. Once I got snorkelling though, I quickly met up with the spiny starfish, a large and very spiny dweller of reefs and rocks amongst the kelp. In St Ives Bay it was the species I came across most often.

It was not until I was in my late thirties though, when we moved to the Welsh coast, that I found the burrowing or sand starfish (Astropecten irregularis) described for science by, guess who, yes, it’s Uncle Tommy Pennant again. A combination of severely cold temperatures and a strong surf, stunned and uncovered them, washing them ashore. They have the ability to sink or sort-of melt into the sand and, as an adaptation to living under the sand their tubular feet do not have the usual suction cups on the end. That same day I found my first cushion star (Asterina gibbosa, and another one named by Tommy Pennant) in a similar predicament. Storms are a great time for beach combing, just be careful and very aware of the tides, when immersed in stars and storms.

Star Struck

We found Luidia ciliaris, the seven-armed starfish, as a family for the first time in 2019 on the west coast of Scotland and have yet to find any of the gorgeous many armed sunstars. I’m not a starfish twitcher, a stargazer you might say, but star struck enough to want to bump into all the British species if I can.

Along with the sunstars there are 8 to 10 British starfish species. One other that blessed us with its presence in Scotland is the entertainingly named Bloody Henry (Henricia sanguinolenta), which has a random splash or splashes of red upon it. It is stiffer with more rounded arms (in cross-section) than the other British species. And is not so predatory, in that it cannot spread its body round large molluscs and destroy them. It spends some of its time collecting particles from the ocean current with its arms raised.

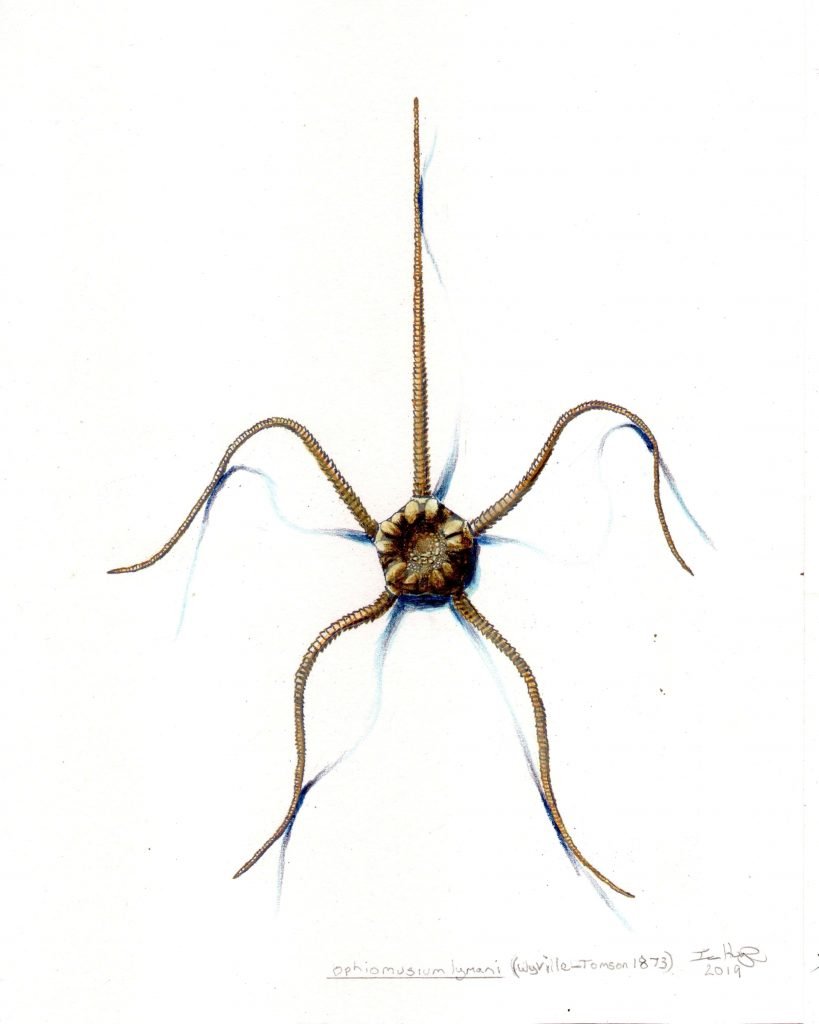

The Ophiuroids

There is another group of echinoderms. They are probably slightly better known than the crinoids and sea cucumbers, but not as well-known as the starfish and sea urchins. The brittlestars are not starfish but are in a class of their own and are the largest group of echinoderms on the planet, with about 1800 species worldwide. Britain has about 27 species of which I have seen, probably two. Although I tend to think that those I find are all common brittlestars (Ophiothrix fragilis) when closer observation of these delicate animals may show them to be crevice brittle stars (Ophiopholis aculeata) or one of the other species without a common name.

Brittlestars

Not only are brittlestars the largest group of echinoderms, they are often among the most abundant animals on the seabed around the world and around British coasts. Sometimes they are so abundant that the seabed beneath them is invisible. With the possible exception of the free-swimming feather star (the stalkless sea lily mentioned earlier) brittlestars are probably the most active, fast moving and agile of echinoderms.

Whereas starfish and urchins glide along on a carpet of suction feet, brittlestars only have such ‘feet’ around their mouths, which they use for feeding. They actually walk using their arms, a bit like commandos crawling into enemy territory. Their gut is not a one-way street like other echinoderms, with an entrance and exit. Anything they eat ultimately comes back out through the mouth. Many brittlestars show obvious sensitivity to light but how they do it is a mystery. The last I read was speculation that the characteristic body scales may be arranged in a way that makes much of the body act as a compound eye.

My first meeting with brittlestars caused great excitement when (aged about 8) I found them dropping off lobster and crab traps (creels) stacked up on the fishermen’s slipway at Filey. Lovely Filey has served me well.

Sand Brittlestars

One cold stormy day we found many sand brittlestars (Ophiura ophiura) without a full set of arms between them, washed up on Traeth Gwyn near New Quay. We threw them back into the sea although their chances on that cold stormy day were slim. I was entranced by them and cast a specimen with one complete arm in plaster. By replicating the arm four more times I produced the complete animal. This particular species burrows beneath the sand and resembles a sand-dollar body, with long arms like snake tail thus the snaky name ophio. Brittle star arms have no tube feet, as I said they are not starfish, and they walk using their arms like a spider, rather than gliding along like starfish do. The segments that the arms are made up of are called vertebrae, so vertebrae do exist in the invertebrate world.

From the plaster cast and photos of the specimen, I drew the picture we have on our T-shirts, our only echinoderm so far, but representative of the group, the Phylum Echinodermata, as a whole. I am fascinated by this group but what I know is the tip of the tip of the iceberg so please go out and enjoy them and learn more.

Echinoderms and Plastic

A couple of years ago, we had the pleasure of corresponding with Dr Winnie Courtene-Jones who wrote a guest blog for us about the deep-sea brittle star Ophiomusium lymani . This brittlestar seems to be the most widespread deep-sea animal there is. And, as the deep sea covers most of the planet, and it often lives in very dense aggregations, is a strong contender for the most numerous animal on earth. Winnie’s work, as a marine plastic scientist, far off the coast of Scotland, showed that these deep-sea creatures have micro plastics in their guts even this far from land. And (using stored samples) that this started happening shortly after the mass production of plastics began and much earlier than a build-up was expected to have begun.

We make our living from selling T-shirts and other products with our illustrations on them. The purpose of them is to project these important world changing subjects out among the people and inspire conversations, which encourage people to care for the planet’s other inhabitants who are now dependent on us, as a species, to do the right thing. You don’t have to buy a T shirt but it certainly helps us write blogs like this.

The Ancestors Reunion

I wonder now about relatives coming back together after a long time and distance apart and what we, the chordates, might say to the echinoderms and what they might say back. Would it be bitchy or complimentary or a bit of both?

“So…, I saw you made it onto land.”

“Yep, yeah we did, and into space, got to the moon.”

“Hmmm, nice, very good, well done. You must be pleased.”

“Well, it keeps us out of mischief so to speak.”

Does it? Does it really? Do you know what we’ve had to put up with since you left the sea, and it’s mostly come from you…?”

Our old home has become our rubbish dump but our relatives still have to live there. I’ve read that the concept of Hell may have derived from threats that bad people would end up on the rubbish dump called Hell or Gehenna outside the city of Jerusalem. It’s a long human tradition to throw and flush rubbish out of sight. Are we creating Gehenna in the oceans, the lungs of the earth? It’s time to show our relatives more respect by the looks of it.

On a bright and hopeful note, the best way to understand our oceans is to study, love and share their wonders. If we all do this and act wisely on what we find, I think we can all have a long and harmonious existence.