Encounters with Cephalopods – Squid

The World’s oceans still hold many mysteries and secrets. For all our exploration, technology and science, the seas around the British Isles are no less beguiling than any around the World.

As a child, I remember looking out at the sea. Most often it was murky and choppy, and I’d wonder, with wonder, what wonders lay beneath. I was able to see fish, snails, starfish and crabs in rock-pools, fishermen’s crates or washed up on the sand, on brief holidays to the coast. I even saw seals and porpoises, all telling tales of what that bit of ocean held.

But cephalopods (octopus, cuttlefish and squid) were more illusive. They featured in books but with very little about the British species and what our coasts might be home to. I wondered if cephalopods were really tropical or sub-tropical and only rare occurrences in our waters. Slowly though, I began to find, that the seas surrounding Britain are entwined in the sucker-clad arms of many cephalopod species.

The Squid Kid

Around about Easter time in 1977 I had my first encounter. We were on a family day-trip in Filey and had been for our essential walk along The Brigg (a rocky peninsula to the north of the town’s beach). Every high tide the path would be consumed by the sea. We were hurrying back to the beach, racing the incoming tide, stopping occasionally to look into rock pools.

Just as we reached the sand, I noticed something floating in the surf, among the rocks where sea, sand and Brigg met at that particular moment in tide. It was pink and white and looked biological enough to catch my young naturalist’s eye. As I approached, I felt like a twit as it seemed to be a large candle that had somehow been discarded on the beach. I almost turned on my heels, but then I saw it bend. So I made the extra few steps to investigate properly. This candle had an arrow shaped fin at one end and tentacular arms at the other. It was floating helplessly in the surf among the rocks and getting damaged by rocks, barnacles and mussels. I shouted… “it’s a squid,” correcting my earlier announcement of… “it’s just a pink candle.”

The prize

As I shouted I bent down and grabbed it by the middle as quickly as I could. Expecting it to dart away quicker than I could grab. To my surprise, I ‘caught’ it by the middle and felt the texture of squid for the very first time. “I’ve got it!” I yelled but everyone was out of earshot, on the beach heading for lunch. I’m not sure why I thought candle rather than rock. It looked just like a jumbo sized stick of confectionary rock, pink with a white underlayer, dissolving, just as rock would, in the waves. I think I only ever had one of those giant sticks. It was sticky and icky, containing too much sugar for one child to eat.

I lifted my prize from the shallow water. My family had realised I had lagged behind and were looking back to see where I was. As I lifted it, the head-end distended loosely from the fin end, almost as if it might drop off. But the otherwise torpid creature raised its arms from a limply dangling position, to a sort-of period ball gown shape and then dropped down again. At the same time a wave of slightly darker purplish pink ran through its damaged skin. Lifting it higher I found myself looking at my folks through its dangling arms and shouting through the noise of the surf… “it’s alive!”

£6

However alive it was, it was either my prisoner or patient and I never saw it move again. Cradling it to avoid it falling in half as I feared, I ran over to my folks. A carrier bag was produced and in it went. In water at first but, apart from slight colour changes in its skin it showed no further signs of life. Never had I been more keen to get home, I had a trophy, a specimen, in need of preservation. I am sure the six quid joke could slip in here but this was such a serious moment for little me, it would have been lost in the excitement.

…the shark owed the ageing albatross some money and took him a cephalopod like mine saying, “here’s that six-quid I owe you”. And the moral is that many a fiddle is played on an old tuna.

terrible joke!

A Kraken good find

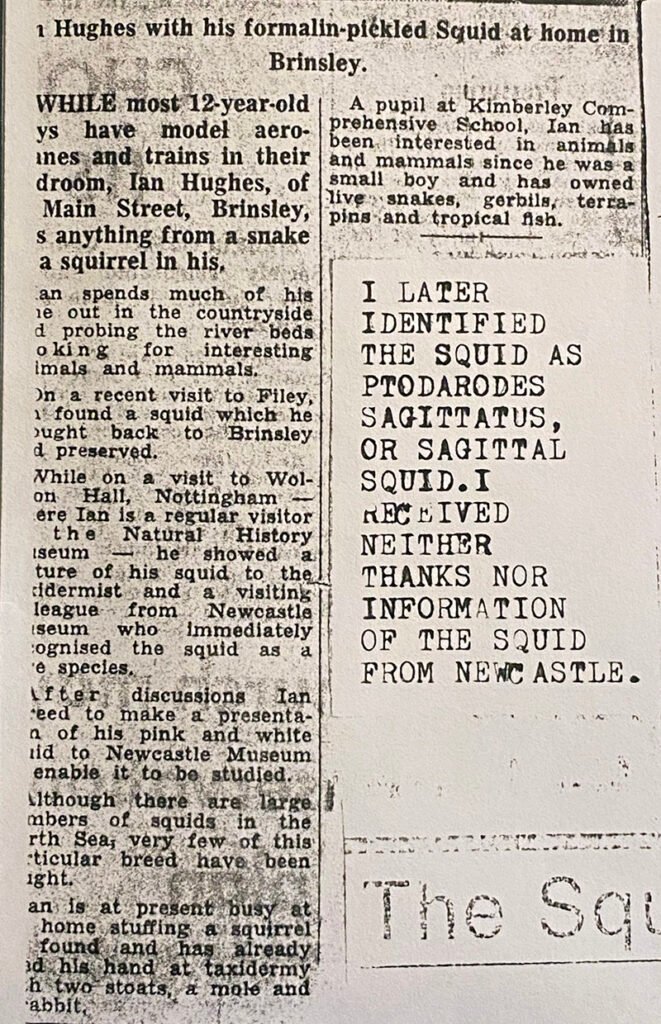

It’s a long story but I had become a regular visitor to our local museum. Also Mum worked at the college, where through reciprocal favours with staff in other departments, she had access to formaldehyde! We froze the squid, as prescribed by the museum, at first. Then, on the Monday evening dropped it into a large sweet-jar full of formaldehyde after taking a few photos.

I should tell you that formaldehyde is toxic and dangerous stuff, please avoid it, what were we thinking!!

I used to stick my photos of specimens into a museum scrapbook. I’d often take the scrapbook, as a sort of show and tell thing, to the museum. Somehow, I can’t quite remember how it happened, I found myself in the taxidermy studio of the museum. There, were my future boss, the taxidermist and a visitor from a Newcastle Museum. The visitor, a bearded fellow, saw my photograph and instantly recognised the species. He told us that waffelopeez zajitartarsuz (or something like that) was known in British waters, but was rare in the north sea. And it was unrepresented in their museum collection, would I be willing to donate it to his museum?

Although it meant losing my trophy, this recognition felt like winning an Oscar. An agreement to hand it over was struck.

Fame at last

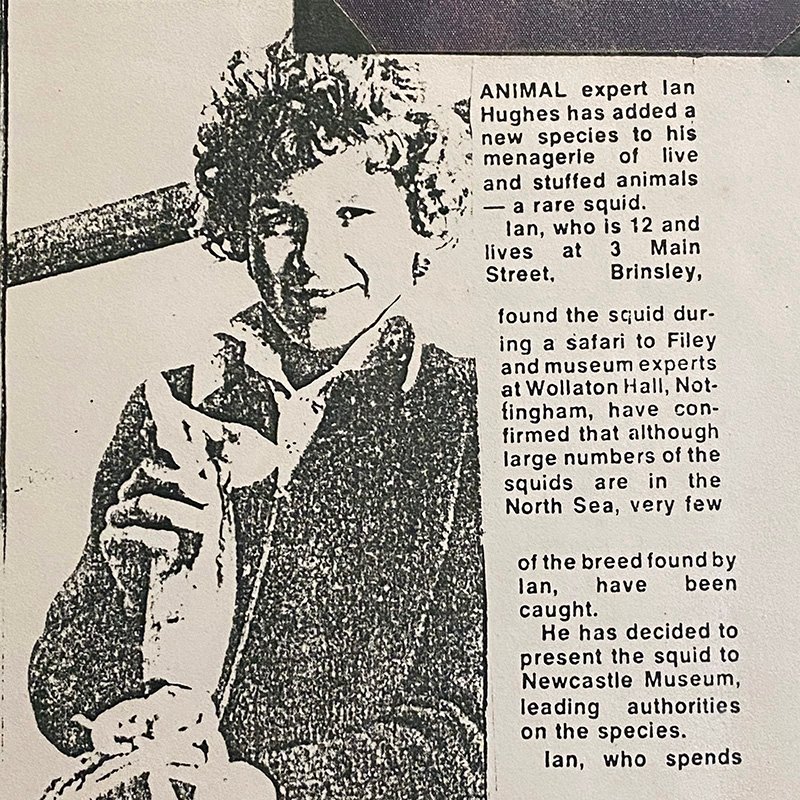

My grandmother was deeply involved in community life in our village. She announced the ‘rare squid’ to a friend and colleague who had connections with the local papers. Soon enough they were onto the story which ‘headlined’ as… The Squid Kid, that’s Ian. Fame at last, I was 12.

We dropped the squid off at the local museum at the next opportunity. We’d made an arrangement to meet the Newcastle chap for the actual hand over. When the day came, we spotted him driving off with the sweet jar on the passenger seat of his car as we arrived. He looked happy enough but I never quite got his name, his museums name or the name he was calling my squid. I just remembered that he said the arrow shaped fin was an identifying feature. I never heard of him or my squid again.

About 5 years later I acquired a little bible, The Hamlyn Guide to the Seashore and Shallow Seas of Britain and Europe. In there, among the 11 cephalopods featured, was what I presumed to be my squid. The author, A.C. Campbell, called it Ptodarodes sagittatus, the Sagittal Squid. The distribution was described as “Mediterranean, Atlantic, rarely in the North sea and west Baltic. I struggled to find it in literature after that, partly because it is now known as Todarodes saggitatus with no P at the front.

Squid – Sagittal or Arrow Squid Todarodes sagittatus (Lamarck, 1798)

Usually described as muscular and powerful, the sagittal or arrow squid is one of the largest in British waters with a mantle length up to 60cm. The mantle is the tubular part with the fins attached to it and out of which the head and arms project like ice-cream and multiple flakes from the cone of a very lucky child.

Flying Squids

It has another name and it is an exciting name too; European Flying Squid. I have found no evidence that this species does actually fly; gliding squid would be more accurate anyway. But have no reason to believe that it cannot, as it possess all the features required for cephalopdian aeronautics. It is placed by taxonomists in the family Ommastrephidae – the flying squids. In his book, Kingdom of the Octopus (a wonderful book for anyone fascinated by cephalopods), Frank W. Lane describes a fairly close relative of the arrow squid, the hooked or club-hook squid, Onychoteuthis banksii (also found in British waters but with a global distribution) with a quote from Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki expedition.

‘They pump seawater through themselves until they get up to a terrific speed, and then they steer up at an angle from the surface by unfolding pieces of skin like wings. Like the flying fish, they make a glider flight over the waves as far as their speed can carry them…. We often saw them sailing along for 50 or 60 yards, singly and in twos and threes.’

Thor Heyerdahl

Lane goes on (quoting Austin Clark) to say that there, ‘is, however, a characteristic of a school of flying squids which clearly distinguishes them from a shoal of flying fish. Whereas the fish are individualists in the air, and make no attempt at formation flying, the squids maintain the same distance from each other as they sail through the air, and the whole school falls back in the sea together.

Great migrations

Our squid is known to be migratory, travelling over thousands of miles through the seasons. Also migrating from the ocean depths, where it spends the day in huge shoals, sometimes over 4000 metres deep, up to the surface to feed at night. I have discovered that, despite what I was told and have read elsewhere, the sagittal squid is common in the northern north sea (the deeper part) and the English Channel as well as the Atlantic and the Irish sea, so not so rare after all. On-line fisheries and offshore energy documents on cephalopods, tell me that ‘The European flying squid, T. sagittatus, forms huge aggregations around the coasts of Scotland and Shetland in certain years [quoting Joy 1990], although by late December the squid have begun to migrate into deeper continental shelf water to over-winter and spawn – spawning depths of 70-800m have been reported.’

Todaropsis eblanae

Interestingly, it reports on another squid we have found, Todaropsis eblanae (the lesser flying squid), which it says ‘is also known to form large aggregations in the region, although the species rarely ventures into shallow or surface waters.’

Well – one stormy night, soaked with rain, I found a fresh specimen. It was lying in the pelting rain between the high tide mark and the sea, which was at low tide at that time. It was so short bodied that I thought at first that it had been cut in half.

A reconstruction of this animal features on our notebooks and cards.

The water in this region is shallow but then quickly deepens. It’s a popular hunting ground for dolphins and mackerel. It also supports lesser flying squid and veined squid we have found. I think our specimen of the former possibly ran into fresh muddy water flooding into the shallow bay. Unfortunately it either suffocated or, in an attempt to escape, jet propelled itself ashore and was stranded. A similar fate may have befallen my squid kid squid, although I think it may have been thrown away by a fisherman.

Cephalopod Inspiration

These encounters led to a passion for all Cephalopods. Which is why our first art collection had to be the Cephalopods. You can take a look at the collection here.

As well as my pen and ink drawings I’m delighted that we have some of Jake’s digital artwork. He has always had a fascination with the nautilus. Kerry has made some cephalopod jewellery pieces and Gwenan has made some exquisite miniature wire octopus sculptures.

There’ll be more tales of cephalopod encounters soon.

Scarborough 14th January 1933

Before I leave Filey behind, and my squid kid days I just want to linger a while in the area. Just up the coast, in Scarborough, something amazing happened which makes the British and UK list of cephalopods more exciting, interesting and humungous by quite a few squirts of ink. About 44 years before my squid encounter, about 10 miles up the coast, a squid washed up on Scarborough south beach that made mine a tiddler. It was, of course a giant squid, the world’s largest living invertebrate and, famously, the owner of the largest eyes in the animal kingdom, dwarfing those of giraffes, ostriches and whales. You can read more here.

The Giant

That the giant squid is a British/UK species, is for me, a wonderful thing to know. It took up the best part of a double page spread in my animal encyclopaedia. Its scientific name is a great one to tangle a young tentacular tongue around with echoes of Tyrannosaurus rex, perhaps the World’s best known scientific name.

The giant squid is Architeuthis dux. Very little is known about it or the British specimens for that matter. Scarborough isn’t the only one, it’s just the closest to my squid kid moment. I wonder how I would have reacted if I had been the one to find it. I have a horrible feeling that their presence in the North Sea was dependent on species which have declined beyond a point that can now support such a predator – bluefin tuna for example – and maybe they have retreated to the ocean depths but hopefully not.

There will be more on the giant squid soon.