All you ever need to know about Turkeys and much more!

A Tale of Two Turkeys

It just so happens that I find myself working on two separate blogs about two separate birds with little, and yet also, somehow a lot, in common. Both found themselves on the stage that is human history but one was a flop – a turkey in the Broadway sense (although I admire it greatly) – and the other was a great success. The latter, however, lives on almost entirely for human use and persecution, whilst the flop had the dignity of flopping in freedom. Both have suffered for the purpose of being stuffed, but with different materials and both fell-fowl of European nautical technology as their historical debut but have associations with humans extending deep into prehistory.

Our first bird is the magnificent turkey, an icon of feasts and terrestrial hunting. The second Bird is the Great Auk, an equally magnificent master of the ocean but an icon of extinction. Neither bird is native to Turkey!

TALKING TURKEY

I like, at Christmas time, to think and dwell on the animals associated with it. You know them, robins, reindeer, donkeys and cattle a lowing. For as long as I can remember, any new animal I have come across, I have fixated on for a while and studied so it’s hardly surprising, with the excitement of Christmas, that turkeys are among my oldest friends. I wanted to talk about the turkey as a bird and a fellow being, rather than as a meal, farm animal, or object of desire but those would be the elephants in its er… barn.

It’s hard to know where to start with the Turkey, it is such an exciting bird, enravelled in World history, festive seasons and folk-language in terms like, cold turkey and turkey shoot so…

Let’s talk turkey.

Introduction – How Turkey’s entered my life

In western/European culture, turkey’s are probably among the first dozen animals that children hear about, partly through Christmas (and thanksgiving in the USA) and partly as a farmyard animal, with gobble-gobble here and a gobble gobble there. But I don’t remember hearing much about the living bird as a child or seeing much imagery. At primary school, one of my classmates grew up on a farm and we walked over there as a class for a day visit.

They had a peacock there which put on an impressive display but I had seen peacocks before at stately homes. There was a cockerel crowing away but I had seen and heard cockerels before too. The animal that was new to me was the majestic turkey, beautiful and ugly at the same time.

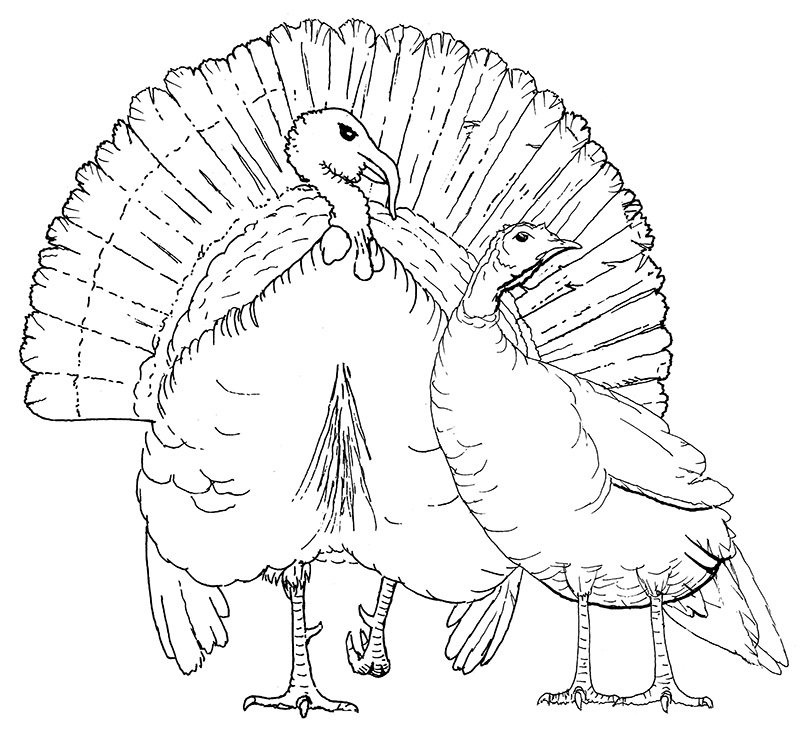

His head and neck were blues, pinks and reds with wobbling, flapping and globular protrusions, desperately inviting a tactile examination, his metallic feathers, and beard rustled as he strutted and shook, his tail, spread like a fan, looked for all the World like an Indian Chief’s head-dress and, to top it all, he gobbled.

It sounded to me like dropping a bag of marbles into the bath. I used to take a huge amount of toys to the bath including a toy turkey. His appearance was unexpected, he looked like a dinosaur. Few people knew at the time that birds are dinosaurs and probably more closely related to crocodiles and alligators than those giant reptiles are to lizards and snakes. A roll of the drumsticks for this please… they’re turkey dinosaurs.

Turkey Dinner

Prior to that experience, Turkeys were a source of humour, (gobble-gobble) and a Christmas feast but the thought of the feast being a dinosaur could only improve it for little me. I’ve always found dinosaurs bootiful.

To my uncultured taste-buds, the meat was pretty much like chicken, it was the size that was impressive. The drumsticks were as big as some chickens and my sister and I would pull the precious wishbone apart with our little fingers and make our earnest wishes. It was magic, so far as we knew and part of the magic of Christmas.

Some remark would be made about how fast it must have been able to run on those chunky drumsticks and my mind would dance away following an imaginary turkey running like the clappers, occasionally looking over its shoulder to see if I was catching up and, gobbling as it ran. For me, it had a funny name, if Turkey’s are mentioned it is usually a funny story or a forthcoming feast.

The turkey was a magic, tasty, funny bird and a potent of good times. I was amused further to discover that there was a country called Turkey. In a favourite rhyme, Hungary ate Turkey, while Italy kicked Sicily. Was Turkey full of a population of Turkeys, was it sizzling away surrounded by, sprouts and parsnips and little balls of stuffing? Surely, Turkey was where Turkeys really came from to live happily on our farms as Turkish Delights? And so I’ll begin.

I find it quite amusing, that Santa Claus, before he was sainted and became an immortal demi-god, was a Greek who lived in Turkey, that Turkey supplanted goose, for many, as a Christmas meal and that Santa is no longer associated with Turkey the country but is with Turkey the bird and that Turkey’s don’t come from Turkey. I once said that to a school mate and he said… “Get-stuffed.”

Early Icons of the USA and UST

The Turkey, the Republic of Turkeys as a species, are not farmyard birds, however charming we make it seem and however tasty or profitable they may be. No bird, is truly a farmyard bird, they all have wild origins.

It sounds obvious but is easy to forget. Turkeys have been domesticated but they descend from wild birds endemic to North America. The UST (United States of Turkeys) includes Mexico and Canada as well as the USA. Endemic means they are found nowhere else so they are very American, let’s hear a bit from Benjamin Franklin, we’re picking him up after a few paragraphs to his daughter, on why he thinks the thieving common or garden Bald Eagle is unworthy of becoming the National Bird of the newly founded United States of America, I have to say, a fledgling republic.

If the President is Potus, it should be known as Nbotus? The USA’s Uncle Ben thought the badge was a retrograde step into royalist style heraldry. He never said this publicly, but here he goes (it’s 1784).

I am, on this account, not displeased that the figure [the eagle shaped Order of Cincinnatus medallion on which the USA national emblem is based] is not known as a bald eagle but looks more like a turkey. For, in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours; the first of the species seen in Europe being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding of Charles the ninth. He is besides, (though a little vain and silly , it is true, but not the worse emblem for that,) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who would presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.

I don’t know how well Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton got along, they have left us no rap song about it yet and Ben, 50 years older than Alex was often abroad. But the pistol swingin’ Alex, now perhaps the best known founding father. after becoming the subject of a hit musical, did like Ben, like turkey it seems. He is said to have said (if you can beat-box him in)…

“No citizen of the U.S.” he said in some short pre-lunch address

“shall refrain from turkey” perhaps he thought it quirky but whose to say

“on” and here’s his specificity not at all murky… “Thanksgiving Day.”

A bird , quite absurd as you’ve probably heard is in a word where the feast occurred. More of a place than a plate, in your face is its fate, across every state at an increasing rate.

Ok, enough of that. This is supposed to be about the bird as a bird and not a captive or a meal.

So, Turkeys are North American birds and were considered grand and important enough for one of the founding fathers (Ben Franklin, the man who, in the Treaty of Paris, negotiated Britain’s recognition of U.S. independence, no less) to consider it worthy to be the nation’s emblem, it’s founding feather so to speak. So why are they called turkeys (?), I hear you ask. I’ll come back to that as it is a little unsatisfying and I would rather stuff your head with respect for the bird first. Sorry to leave you cold turkey but it’s better this way.

The Magnificent Bird

I can think of no-one better to describe a Turkey for you than David Attenborough, writing here in a quote I plucked from the Life of Birds.

The male wild turkey, that grandest and most magnificent bird of the north American woodlands, has in addition to his spectacular feathers and the strange hair like tassel dangling down his chest, a naked neck hung around with swags of wattles. These vary in size. A bird that is not very fit, plagued perhaps by an infection of internal parasites, will not have such big wattles as a bird who is in the peak of condition. And as a bird gets older, so his wattles grow bigger. But they can also quickly change colour. Usually they are purplish red, but if a male disputes with another, perhaps over access to females, then they will rapidly flush bright scarlet. So do those of his rival. As the two contestants square up to one another, the difference in the size of their wattles becomes very apparent. The male with the lesser ones, daunted by the sight in front of him, , rapidly backs down – and signals his submission by a rush of blood away from his wattles that, within seconds, fade from bright red to pale pink.

Sir David Attenborough

Galliformes

From a flush to a blush, that’s the colour changing Turkey. What’ll we talk about next? Let’s do the sciency bit. Turkey’s are fowl. That is they are in the Order Galliformes along with other fowl such as chicken, grouse, quails, ptarmigans (brown in summer, white in winter), partridges, pheasants, guineafowl, francolin, junglefowl and peafowl, comprising, together, about 290 species around the World.

They are so varied, that, if all the other birds (owls, pigeons, ostrich, parrots and penguins etc) were lost, they would still represent respectable diversity in form and colour to stand proudly alongside mammals, reptiles and amphibians and I really, really like those other terrestrial groups. You might hear or see Galliformes described as game birds or game, as opposed to big game (elephants, rhinos etc) and waterfowl, ducks and geese etc which are all hunting terms.

The name Galliform is derived from Gallus, the Latin for cock (as in poultry). But the grand and magnificent, colour changing Turkey is not just lost in the crowd of other fowl, it is the largest of the Galliformes, the heaviest fowl. So heavy, in fact, that it supplanted its fellow, feather-festooned fowl of fantastical feasts, the peacock.

Meleagrididae

Among the fowl, Turkeys sit in the sub-family Meleagrididae which is represented by the two Turkey species, the Turkey (no surprises there) and the Ocellated Turkey; Meleagris gallopavo and Agriocharis ocellata respectively. Let’s talk about the latter first. It’s a beauty but it’s not our bird at the moment. The rare and once almost extinct Ocellated Turkey is native to Central America, is named after the eye shapes, or ocellations, on its tail feathers. We’re passing it over for now but please check it out. It is not the bird of the Thanksgiving and Christmas feasts which is our target.

The North American Wild Turkey is divided into about 7 sub-species. The Eastern Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo sylvestris), wild bird hunted by the Wampanoag people was the one eaten by the Pilgrim Fathers at the original ‘Thanksgiving’ in 1621 and the Mexican Turkey (M.g. gallopavo) is the one that was domesticated by the Aztecs and whose descendants are eaten around the World today. Sounds more exotic now doesn’t it? Mexican Turkey is exotic, yes, but Aztec Turkey requires a humble bow.

But wait a minute. Mexican Chicken and KFC for that matter, derives from a bird that originated in south east Asia and Turkeys (who share their name with a country straddling Europe and Asia), originate from Mexico? It’s a crazy World. Furthermore, the Thanksgiving Turkey was not the sub-species of Turkey that is now traditionally eaten at Thanksgiving. Well, it wasn’t, but now it partially is! More on that later.

Kidnapped or stolen

It should be noted, talking turkey again here, that, as with Columbus Day, Thanksgiving is considered by many to be more appropriately considered as “a day of mourning”, and an inconsiderate celebration of the genocide and conquest of Native Americans by colonists; accompanied, it must be said, by an ever growing fad for turkeycide! The whole point of the Thanksgiving meal is that it is made up of foods native to America (or the Americas) with turkey having become more prominent among them to the point that Thanksgiving is now known to many as Turkey Day… gobble gobble.

A good while before the Pilgrim Fathers were feasting on wild turkey with native Americans who had suffered a severe epidemic (brought in from Europe) just beforehand and then had shown the disease carrying Europeans how to live off the land, before suffering death at their ever-thankful hand, domestic turkeys were heading east for Spain from what is now Mexico and the Caribbean. These were not pirate Turkeys aboard a privateer vessel hoping to conquer the Iberian peninsula, but just prisoners, livestock, being transported as a new food, booty for the King and commerce.

Columbus

Columbus opened up the Americas to Europe in 1492 and, as early as 1500, Pedro Alonso Niño (a former pilot in the Columbus fleet) is reputed, according to my Encyclopaedia of Animal Life, to have arrived back in Spain from a subsequent expedition which may have included Turkeys.Niño, like other early explorers of the New World, was thrown in prison on his return and died in custody, so we don’t have as complete a record of his activities as might otherwise be the case.

Turkeys may have arrived later with Columbus himself or slightly later still. It is impossible to know without further evidence popping up as the adventurers were calling the various fowl they found, peacocks; Pavo in Spanish. What this probably does tell us is that birds of such a name were highly prized for meat as that was the peafowl’s long-founded reputation. They do both strut about similarly though and spread their tails in display. We know turkeys were in Italy by 1520 and in England by 1524.

Turkey – An American Story

The most compelling evidence I found, following up the Pedro Nino story in a book called Turkey, an American Story by Andrew F. Smith is from a 1518 expedition led by Juan de Grijalva exploring Mexico and Yucatan. This was followed in 1519 by Hernán (or Hernando) Cortés and the Conquistadores arriving in Mexico who were to bring about the fall of the Aztec Empire and somehow causing the death of the Emperor Moctezuma, their host, in his capital, Tenochtitlán (present day Mexico City). Moctezuma (a type of Conquistador himself having expanded the empire to its all time zenith) jostled politically with Cortés, sending him six golden turkeys (never show a thief your wealth is the lesson here!) and then inviting him into the palace where Moctezuma eventually became a prisoner.

The six may have been a significant multiple of three. Turkeys were emblems among the indigenous people and a cliff house excavated in Arizona bears a beguiling mural which has earned it the name, The House of Three Turkeys. Three turkeys for luck perhaps; six for double luck and please go away now Cortés. Also significant is the singular domestication of the turkey, a bird.

In Eurasia, in the time since the future indigenous Americans departed from their Asian ancestors, the ‘Eurasians’ domesticated mammals… cattle, sheep, goats and pigs as well as chickens. They, we, shared our dwellings with our livestock and thus shared pathogens that still trouble us today in the form of ailments such as measels, mumps, chicken pox and flu. All this baggage was aboard the ships that sailed to the New World where no such mammalian house sharing had gone on to prepare them, pathological, for such an invasion.

Assisted by the diseases they carried, deceit and warfare with superior technology, conquest of the Aztecs might well be described as a ‘turkey-shoot’, but the Conquistadores took Turkeys which existed there as both wild and domesticated (results of ancient Aztec farming practices), along with anything else of use, to the colonies and back to Spain. This penetration of the mainland and business/colonial approach, if not the beginning, seems a likely start of the steady flow of Turkeys to Spain and Europe.

Aztecs

We’ll probably never know what really went on in that 30 year period. A lot of fibbing, mis-recording and leaving out of information went on, along with forgetting and not calling things by the same name. All these things happen today.

Let’s back track a little. Turkeys were, once upon a time, wild birds in what is now Mexico but were already domesticated when the Aztecs conquered the area around 1200. This is no small matter. Turkeys are pretty much the only native north American animal to have been domesticated, ever! They probably, unwittingly, contributed greatly to the Aztecs success and expansion and were, arguably, the greatest booty, in terms of farming to come back to Europe from the Americas – the real Aztec gold! The Aztecs called the male birds Huexoloti, they had a different name for the hen, but also had a turkey-god, oh yes, here we go… Chalchiuhtotolin, meaning The Jewelled or Jade Bird. It certainly was a gem for Spanish farmers and royal courts across Europe.

Turkey Gods

Chalchiuhtotolin was a confusing god of disease and, as I interpret it, twisted fate. A teaser and tempter perhaps who could bring about the undoing of people too ambitious, but also cleanse people of guilt.

It’s ironic, I think, that the first Conquistadores must have tasted turkey as guests of their Aztec hosts (early, though not the first depicters of turkeys in art, as can be seen in the Borgia Codex and Borbonicus) just as the Pilgrim Fathers did with the Wampanoag at the ‘first Thanksgiving’ about 100 years later. In both cases the hosts were later subjugated and their turkeys and hunting grounds taken as loot.

Long before all this, turkeys were absorbed into human societies over 5000 years ago and depicted in art dating back to the Aztecs and beyond.

To Europe

Some domesticated turkeys, especially youngsters, can fly but the ability and propensity for it has been eagerly bred and fed out of them. Wild turkeys don’t fly far if they can help it but when they do they fly fast, over 50mph. Their legs can carry them along at 20mph. The Aztecs had created a different , slightly smaller, bird and it was this pedestrian and tame breed that arrived in Europe in the early 1500s and, through its size (still huge compared to other fowl) and tastiness quickly spread throughout the continent with further selective breeding.

The Norfolk Black Turkey is sometimes called the Black Spanish or just Black Turkey and is considered to be the closest breed to the original Mexican birds; booty, looted from the Aztecs. I think I prefer Mexican Black or better still the iridescent Aztec! Over 40 turkey breeds have been developed such as In Britain: Bronze, Cambridge Bronze, Crimson Dawn, Norfolk Black (sometimes referred to as the Black Spanish or the Norfolk Black, developed in Europe from the Mexican turkeys brought in by Spanish explorers.), British White, Slate, Bourbon Red, Buff, Cröllwitzer. Narragansett, Pied

And in the USA: some of the above plus White Holland, Beltsville Small White, Royal Palm.

Anyway, Darwinian evolution is present in selective breeding just as much as it is in natural selection but, as much as it is survival of the fittest, survival of the fattest might be more appropriate as turkeys spread across Europe with the help of people who would probably go to turkey hell, stewed and basted in their own juices, into the halls of the wealthy and powerful.

To England

The arrival in England in 1524, mentioned above, was in the court of Henry VIII. A Yorkshire Gentleman, adventurer and Navigator William Strickland is usually credited with bringing the first turkeys to Britain. His coat of arms has a male turkey as the family crest and is possibly the earliest European depiction of a turkey. His Wikipedia pages says; “The church at Boynton is liberally decorated with the family’s turkey crest, most notably in the form of a probably-unique lectern (a 20th-century creation) carved in the form of a turkey rather than the conventional eagle, the bible supported by its outspread tail feathers.” Interestingly, Strickland was a staunch puritan member of Parliament and the puritans and turkeys were to become enravelled in history and modern day turkey lore.

The next most famous turkeyman after Strickland was probably Bernard Matthews, like Mr. Kipling, but a real person, he appeared on our TV screens in what I thought was quite a Hitchcockian ways and told us, his turkeys were bootiful. Booty they were. I thought I might be able to connect Matthews to Tudor Turkey farmer origins but in fact he started off in 1950 with an incubator and 20 eggs and went on to become Europe’s biggest turkey producer; bountiful!

It’s quite possible that in a dystopian, post apocalyptic world, you know the one we seem to encourage daily, turkeys descended from domestic stock birds might just survive us and naturalise in Europe. They almost survived their wild ‘cousins’.

Back in the USA

Bizarrely, as British explorers picked up the trans-Atlantic fever and the Pilgrim Fathers travelled west to create a fairer, purer World… domesticTurkey’s possibly went with them. Not as explorers but behind bars again as prisoners.

“The good news is guys, you’re going home, yay, happy day, congrats, guys, congrats!”

“You’re wording sir, infers some bad news also, but can it be that we are finally free and returning to warm dry, arrrrr, home-sweet home, Mehico?

“Er, not exactly, you’re off to slightly chillier New England but it’s still very nice there. The bad news is you’re going as food. More like home suet home.”

Pocahontas

A list of supplies to the new British colonies in America from 1584 list both sexes of turkey and they certainly arrived in Jamestown (Virginia) in 1608 with English Settlers (The Virginia Corporation of London), possibly less than 100 years after leaving Mexico with Spanish explorers. Jamestown of course is famous for being the first, tentative and troubled English settlement in what would become the USA and its connection with Pocahontas who is buried at Gravesend beside the River Thames. The Show-casing of the Princess to the British crown and people turned out to be a bit of a turkey. Her immune system was just not up to the challenge of mixing with people who had 8000 years of toughening up with domesticated mammals.

Around 1620 the Pilgrim fathers, (just plain Pilgrims at the time) landed and settled in Plymouth. A place they called Plymouth anyway. (The Puritans came ashore about 10 years later in Boston just to the south.) The domesticated Aztec turkeys seem, to some extent to have been cross-bred with New England and Virginia turkeys to create other breeds which crossed the Atlantic yet again.

This brings us to my own relationship with Turkeys and Atlantic crossings.

Traumatic Tales at Turkey Time

You may recall me mentioning that turkey was almost synonymous with my childhood Christmas and that is true for Children in many parts of the World. Christ, of course, if he actually existed, never saw a turkey and neither did St. Nicholas.

The first sign of negativity over turkey was a school friend complaining about having to eat nothing but turkey in the days after Christmas. I hadn’t considered it an issue, nothing ever seemed to be wrong in the time of celebration. Then, one Christmas, Christmas Eve in fact (and please don’t pity me here I’m just using my own examples to talk about how big turkey, even in death, can be in our lives), my Mum sat me down on my bed and told me that, after Christmas, she and my Dad would split-up. It was, she said, between her and me. I didn’t know exactly when it would happen, or how and began to dread it.

Every year of my life, I had wished Christmas to come quicker but now I wished it wouldn’t come at all. But it came all the same. We opened our presents as normal and then sat down to Christmas dinner. Is Christmas dinner after Christmas? It could happen anytime now. We sat around the giant bird and I realised that we were probably doing this as a family for the very last time. Nothing seemed wrong and yet everything was. I was in on a secret that I thought nobody knew but I really really really felt like crying. I stared at the turkey, stared and stared and stared until I had regained my composure and watched the bird be ‘split-up’.

The evening passed and boxing day dawned. Out came the turkey again and my Dad’s sister and family came to stop over for a night. Was this part of it? Would he go away with them?

The wish-bone was extracted, my sister and I wrapped our little fingers around it, closed our eyes, made a wish and pulled. “I wish them to not split up.” The wishbone split and we opened our eyes. I hoped my sister had wished the same thing because she’d won the wishbone. Nevertheless, as Christmas waddled away I began to hope that it might not happen, there was no mention of it, no sign of it. My Dad and I got into a play fight, a chasing game round the sofa. Playing with Dad had become much less common and I was elated to be doing it, giggling, delighted but he slipped, banged his ribs on the arm of the sofa and needed to take a breather. He was pretty sure he was just bruised and winded but reminded me that he had broken his collar bone years before. They break easily, he said, like wishbones, they are wishbones.

My Aunt and Uncle left without Dad going with them and I became more hopeful. Another day dawned. There was bustle when I woke up.

We’re going to Leeds, said Mum,

Why?

Uncle Ken forgot his slippers

Can’t we post them

No, he’ll need them tonight

Are we all going, my sister asked. I didn’t want to ask anything. I did not like this.

Dad’s staying. His ribs are hurting.

I caused his rib pain. I double dodged and he fell. My actions were making this happen.

I could stay with Dad? To look after him?

No, he’ll rest better on his own.

Soon we were reversing out of the drive and Dad came to the window. He never did that, he always got on with things but he came to the window with his injured ribs to wave us off wearing a rusty coloured jumper. It was agony. I had never pitied him before but was now overwhelmed with it. Has he got anything to eat? I asked in the hope he would have to come with us in order to eat.

He’s got cold turkey, said Mum, plenty of it, we turned the corner on the drive and he was gone.

There was cold turkey in Leeds too and it was over cold turkey sandwiches we did the rounds, telling the relatives the news. We stayed the night and when we got home, Dad was gone. They’d split up, like a wishbone.

More Turkey Trauma

About 8 years later, over cold turkey, my step-mum urged my Dad to spill the beans. They had something to tell me. I’d been working away. I couldn’t imagine what they would be nervous to tell me, they were never the nervous types. My step mum spilled the beans. Your Dad’s got a job in the states, she said, we’re moving out there around Easter. Temporary?… or permanent? I asked hesitantly.

It’s a permanent job.

Easter was a while away and I thought, hoped, I guess, although I wished them no bad luck, that it might fall through. It did not, and Pickfords moved my Dad and step family to America.

Thanksgiving

I’m a bit like a turkey. I can fly but choose not to unless I have to. Four years later I visited them for the first time at their new home on the New England coast. I had missed the autumn colours, the lobster and whale watching seasons but was there in time for Thanksgiving and there, in the land of the first American Thanksgiving, we sat around a giant cooked bird as a family, reunited. I had heard of Thanksgiving but not really paid much attention, it was an American thing of little relevance until that Turkey Day. The following day, I packed a cold Turkey sandwich, and headed south. I wanted to get to Cape Cod, I was looking for living horseshoe crabs. I stopped off at a seafront, to have a bite to eat and a drink and looked out to sea. It feels like you are looking back towards Britain (where my girlfriend and future wife was) but the true trajectory, perpendicular to the coast, is more like South Africa.

I noticed to my left a large memorial. I walked over to read it still munching turkey sandwich. It was Plymouth rock, supposed landing place of the Pilgrim Fathers in whose name a lot of Turkey eating is done even if, so some say, they didn’t eat turkey at that famous feast. I was never Turkey meat’s biggest fan but it seemed to be following me!

No sooner was thanksgiving over than December rolled in. A neighbour and good friend ushered us into his giant car. “Six o clock” he said, “wer gotto get there at six o clock. Every Friday in December at 6, the bartender put a whole cooked turkey on the bar for all to pick at, free of charge. Let’s go get us a piece of the butterball bird.” He was very excited and there was indeed, free turkey for all. This is mass produced turkey that has had a short grim life no matter how happy it makes the punters.

More Family Turkeys

Many years later, we all gathered together at my Sister’s home in Cornwall. It was summer but she insisted on cooking us a Christmas dinner because we never got to spend Christmas together and we all sat round a turkey again. It certainly seems to be a special bird that hits a mark with many people and I cannot claim immunity.

Thanks to Bob Newhart, I thought, erroneously, that Turkeys were discovered for Europe by Sir Walter Raleigh. In his telephone conversation with ‘Nutty Walt’, Bob confirms the arrival of the boat load of turkeys and tells him that “they’re wandering all over London as a matter of fact.” As a matter of fact, turkeys were wandering all over London when Nutty Walt was a boy. As early as the 1560’s when Raleigh was about 10 years old laws were introduced to prevent poultry farmers from letting their turkeys wander the streets where they were creating a “common annoyance.” Turkeys were breeding so well they could, in the right season, be cheaper than chicken. Birds going cheap! Raleigh’s biggest turkey (in the Broadway/Hollywood sense) was the establishment of the English Colony at Roanoke, who became The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island.

Goose bumped

You will probably know that there is a traditional bird for the Christmas feast in Britain and it is not the Turkey but a goose. From its arrival though , turkey gained popularity, first as a royal delicacy and then by royal imitators. Turkeys became popular with farmers, especially in the east of England and were herded like cattle along droveways to market 100s at a time. The more numerous they became, the cheaper the price and more people ate them. Turkeys were considered a bit special and supplanted goose in many households, a process that had been on the go since well before Dickens wrote a Christmas Carol although Dickens probably helped popularise it further and had visited the States in 1842 and been fed turkey, he was a fan of that fan tailed bird and, surprise surprise, published a Christmas Carol the following year. Did he scribble out ‘goose’ and replace it with ‘turkey’ after that meal?

Turkey is conspicuous by its absence from the 12 days of Christmas song. As the 12 days start with Christmas Day, perhaps the turkey has been and gone. Still, I’d like to slip a walkie Turkey in there, just for fun.

Back to the wild

Whilst their domestic cousins sailed to Europe, from where their progeny would return, no more free than before, free turkeys. In the land of turkeys faced life with Europeans as settlers. Whilst seen as food and decoration by the indigenous Americans who arrived at the end of the last ice age, they had survived pretty well where others had not. Giant ground sloths, Mastodon, mammoths, steppe Bison and giant beaver, among others had fallen in this time. But the giant fowl had prevailed. I should say that it was smaller than the aforementioned meaty giants and almost as fast as an arrow.

Europeans flocked to the shores of the New World, a land of great promise and pushed inland. The gun had arrived in America. Wild turkeys get many mentions in the documents of early colonists and settlers and were clearly an important food source.

Being communal, territorial and a bit nosey, turkeys could be lured into traps and ambushes. Native Americans led the way but European settlers took it further and, with lead shot, were able to kill more birds. In a world where bigger is widely considered to be better, the wild turkey, as north America’s largest game bird, was in an unfortunate position.

Turkeys are essentially woodland birds, they like to roost in trees and forage under cover and, when the Europeans arrived in the Americas, occupied woody, scrubby habitat from what is now Canada all the way south to what is now Mexico. A single species, Meleagris gallopavo, but divided into sub-species.

· Eastern Turkey M.g. silvestris (Viellot, 1817) – the most widespread (all the eastern states) and also found in Canada

· Florida or Osceola Turkey M.g. osceola (Scott, 1890) – the smallest. Restricted to the Florida peninsula

· Rio Grande Turkey M.g. intermedia (Sennett, 1879) – found north of the Rio Grande through Texas and Oklahoma to Kansas

· Merriam’s Turkey M.g. merriama (Nelson, 1900) – Ranges around the Rockies and north/north-west USA. Also found in Canada and used for introductions in the central USA

· Gould’s Turkey (M. g. mexicana) (Gould, 1856) – Considered to be the largest wild turkey. Found in Northern and western Mexico, southern Arizona and New Mexico. It was heavily persecuted and is protected.

· Mexican Turkey M.g. gallopavo (Linnaeus, 1758) – Probably the second smallest sub-species. Restricted to Mexico but globally distributed as the domestic Turkey. Naturalised as feral turkey in Australia.

Persecution

Persecution through tree felling for timber, forest clearance for farming, subsequent ploughing and hunting for the market and as crop-pest extermination, drastically reduced turkey numbers until they had disappeared from most states except those in the south. By the 1730s, little more than 100 years after the famous Pilgim/ Wampanoag feast, wild turkeys were dwindling in New England although populations hung on in Massachusetts, Vermont and Connecticut until the 1800s. The last record for New York was 1844, the last year for Great auks too and on it went.

Chilled and frozen turkeys from western and southern states were railroaded to the east to feed the demand and so turkeys declined there too. Kansas was turkeyless by 1871, South Dakota – 1875, Ohio, Nebraska and Wisconsin in the early 1880s and Michigan in the ‘90s. In the first decade of the 1900s, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and the Canadian Province of Ontario had annialated their wild turkeys too. Dependent in the wild on foods like acorn and chestnut, turkeys suffered along with many other bird species as oaks were felled and the American Chestnut disappeared through disease brought in on imported exotics.

Predicted Extinction

In 1941, the conservationist, Harold Blakeley reported that there was only one small flock left in east Texas, turkeys were a rarity in Oklahoma and were restricted to private reserves only in the south of Georgia. Many predicted extinction and the future of the wild turkey seemed bleak.

However, as early as 1876, individual conservation actions were taken and the sale of frozen turkeys between states was banned by the Lacey Act in 1905. By the 1950s translocation of turkeys to their former range was well underway partly using a levy on sports-gun ammunition put in place to support wildlife conservation. Flocks were trapped using cannon nets (exactly as it sounds!) and drugged bait and by the turn of the century the US wild turkey population had risen to over 5 million from perhaps 50 thousand just 50 years before. It was driven more by hunters than vegetarians, but it is a conservation success story for the species. They are now more widespread than any other American game bird and are attracting hunters – carefully regulated ones – galore.

Feral Turkeys

The world of turkeys is, like most of the wild, a bit messed up now because the appropriate sub-species were not always used for introductions and many populations are hybrids. Feral turkeys have become established in many other countries including Hawaii, Australia and New Zealand which have or had endemic wildlife assemblages which have proven very sensitive and vulnerable to introduced alien species.

I get the feeling that tales of turkeys will go on and on. Globally widespread and increasing, the only large scale domestic animal from North America and one of the biggest attractions and money makers in both hunting and farming. Meleagris gallopavo is a success as a species, because of its tastiness.

Through a turkey’s eyes

Turkeys, of course, are not striving for tastiness. In a Darwinian sense it has been a double edged sword for them. They are persecuted but have found, in humans, a protector and chauffeur to new horizons where some formerly imprisoned turkeys can now be called ‘free’. Some aphids survive in the protection of ants and many species, lions, polar bears, whales and bats among them, rely on the flesh of others to survive. But that is what turkeys are innately striving for, survival, to stay alive, to not be eaten and to live without fear or the boredom of imprisonment.

Turkeys are like us. Bipedal, sociable and vocal. They are also omnivorous and it is not impossible to see the world from their point of view. We, like them, wander around our society looking for social and sexual opportunities, good food and a comfortable safe place to sleep.

I heard an amusing quip recently when most of Wales voted for Brexit in the referendum despite receiving much of their cultural support from the EU. “It’s like turkeys voting for Christmas,” they said.

An Unpleasant Ending

What better way to empathise with this bird, they would never vote for Christmas, thanksgiving or an extended shooting season, all the things that mark their association with us despite our shared traits. In Britain alone, about 22 million turkeys are raised for meat every year, most of them on intensive farms where they never see daylight. Although they have about a 10 year natural lifespan, commercial birds are ‘harvested’ at younger than 30 weeks old being shackled, hung upside down, stunned and then killed. Many have been bred or fed to such proportions that they cannot mate effectively (even if they had a decent opportunity), let alone fly, and are artificially inseminated. Turkeys like this are, to top it off, tasteless and require added flavour so may as well never have gone through the process at all for what nutritional and gastronomic benefits we humans get from them.

Whilst we have not been entirely bad for turkeys, we exterminated many of their post-glacial predators and created turkey hotels around the world where they can breed without predation and with enhanced protection from disease, I can’t really see any turkey, if shown the full picture of our association, liking us. It would be like us finding out that the sun is just God’s kebab roaster for the lightly seared humans he loves… hmmmm?

Turkey Facts

Male and female turkeys look spectacularly different from each other, like men and women or lions and lionesses. The males (collectively known as cocks) are much larger than females (hens) and conspicuously coloured and ornamented while females harmonis with their surroundings to provide the nesting camouflage they need. They are highly gregarious and sociable birds gathering in summer harems and, in winter, smaller single-sex flocks within more widespread flocks. They stay in constant communication, to stay together and to warn each other of danger as well as to communicate more intimately; like our own news broadcasts and conversations. Turkey conversation is one of the main characteristics that has been taken advantage of by wild turkey hunters, of which there are an estimated 2.7 million in the USA today, many of them deceitfully pretending to be turkeys. If one turkey calls to see who’s about, others dutifully answer and move towards or away from the caller accordingly.

Turkeys fly only reluctantly either to roost at night or to escape predators when they can get up to 50mph over distances of less than half a mile; a few hundred metres.

Male Turkeys are known as toms until they mature at two years old and begin herding harems in spring, when they become ‘gobblers’ (sometimes called stags by turkey breeders). The gobbler has a bare and colourful head and neck, a spectacular fanable tail, iridescent plumage and a beard on his chest which grows with age, so long sometimes, that it drags on the floor. Over his beak or bill, hangs an extension known as a snood.

The name is gobbler onamatopaeic – galobble, obble obble – for the wonderful mating call which attracts hens into his group. He is now in resplendent plumage with all his wattles and accescories in full colour and like many harem formers, will self-starve during this time. He puts on a display while he gobbles, known as strutting. Often two turkey males will strut together, teaming up to former larger harems but, any other gobbler who tries to take his hens, will face a full gobbler display with tail spread and chest puffed out, wings hanging. If neither one backs down, they fight.

The famous ornithologist John James Audubon described a gobbler fight

“Their wings drooping, their tails partly raised, their body feathers ruffled and their heads covered with blood… If, as they thus struggle and gasp for breath, ” he went on. “ one of them should lose his hold, his chance is over, for the other, still holding fast, hits him violently with spurs and wings, and in a few minutes brings him to the ground. The moment he is dead the conqueror treads him under foot but what is strange, not with hatred but with all the motions which he employs in caressing the female.”

Secret Nests

Once mated, hens slip away to create a small scrape in the ground which suffices as a simple nest. This is a vulnerable time as they normally roost in trees. Here she lays a single egg and then returns to the harem. Gobblers can destroy eggs so she must keep it secret but returns again and again until she has a clutch of 10 to 15 eggs which she incubates for about a month until they hatch. The young can run almost straight away but, until their flight feathers and muscles kick in, speed and camouflage, along with a protective mum and flock, are their only defence from predators.

Flocking and communication are essential to turkey survival just as they are to people. According to the USA’s National Wild Turkey Association, the most important, or imitatable ones are: assembly yelps, attention clucks, reassuring cluck/purrs, excited ‘cutts’, excited yelps, cackles, courtship gobbles (males), I’m lost kee-kees (youngsters), plain hen yelps (I’m a hen and I’m here it seems to mean), reassuring purrs, alarm putts, muffled tree yelps (roosting birds preparing to descend).

They do not list the sound that is the subject of the last part of my blog…

Why Turkey?

Turc, turc, turc is the onomatopaic theory on how the turkey acquired its English name.

I’ve read one account which states that turkey’s don’t go “Turc, turc turc but I think a few of the calls above could be interpreted that way, more so than they could be interpreted as Tach, tach tach but that’s not helping!

Before I go on, I’ll put the over-discussed subject to rest by saying that nobody really knows how the name came about and it is a purely English speaking conumdrum of little importance to anyone except perhaps zoological etymologists who can, I’m pretty sure, survive without a definitive answer.

Confusion

People are really good at finding an easy, lazy or funny name for something and the most memorable simply tends to stick. I grew up knowing Santa as Santa but, teachers and purist colleagues would, rather condesecendingly, call him Father Christmas despite the fact that he is not the father of Christmas and only his ancient (lower case a) Greek self had any ecclesiastical status that might attract the appellation. We don’t really know why we have know and no as well as two, too and to or through and threw.

The accepted route of domestic turkeys is not direct from the Americas to Britain but to Spain and the Mediterranean and then to Britain. There are two claims or theories of how it got here, both could be right (not write) as turkeys were being dispersed all over europe; their large clutches, coupled with what was probably a prodigious import, make the tasty exotic birds and easy commodity with an existing poultry trade to fit them into.

What’s in a Name?

There is a beautiful fish called the angler fish in British Waters which, in my lifetime has had its name changed by restauranteurs and fishmongers to monkfish which was formerly another name for the angel shark. Similarly coneys became rabbits among many other name changes or class differences over the course of time. Some people call their customers punters in private but never to their faces and the name turkey may have crept in like that, as a traders name.

The early Spanish explorers and conquistadors were calling the birds pavo or pava, the name still used for both birds with peafowl simply elevated to Royal, Pavo Real. If the birds arrived via France there is little to cling to there as their name, Dinde, is an abbreviation of Poulet de Inde, referring to its origins in the west indies, named as such by Columbus who was looking for India by travelling west and thought he’d found it. Just a bit further on mate! Unless French or Spanish farmers or market traders used a different name (which is very possible) birds coming in from either place would probably have been given similar names or names of similar derivation at least.

and the boring answer

The most boring and probable source of thew name is one cobbled together by traders who used terms like Guinea and Turkish for exotic or foreign and both the turkey and the guinea fowl were in that realm and got mixed up with Turkey being used for birds before Columbus arrived in the Americas. Its possible that enough people, or just the right person, was calling edible foreign birds Turkeys because their punters wouldn’t understand if he used another term or he had forgotten the name. It’s easy to imagine.

Watcha got there mate, they look plump and tasty, how much for the lot

Esta Pavo Signor

Its what mate

Is Pavo, er Coq de Inde, no?

I don’t know mate, they look like them Turkish fowl to me only bigger

Yes, Turke, turke, is like that

Alright mate, give us a good price and I’ll take all them turkeys orf your hands an’ ship ‘em to blighty

Then, at the other end…

There called Turkeys mate, take ‘em or leave ‘em I haven’t got all day but they’re the only ones in England, nice an’ meaty, fit for a royal feast Sir.

It is possible that Turkeys along with their name, were traded not from Spain or France but from Italy where they had arrived by 1520 and spread quickly among the populace whence the lower classes, apparently imitating the bird’s turc, turc turc call, changed its name from the one they’d been given to Tacchino.

It’s a what mate, I can’t ‘ear ya over the gobblin’ an’ turc turc turcin’

Tacchino

Tukino?

Ci Tacchino, tike em or a leave ‘em

Oil tike em mite. Oi Bryan, ship them turkis! Pronto, they’ll be the first in Engaland

It is a bit of a smoking gun that the Italian and English names are so similar regardless of the original origin, it seems highly likely they are shared.

William Strickland is widely credited with bringing Turkeys to England for the first time and was sailing with Sebastian Cabot who was to all intents and purposes… Italian – a venetian explorer. The two travelled to the new World together vin 1508-9 with Cabot as Captain and Strickland as Lieutenant and although they only seem to have reach the Delaware river could have acquired Aztec turkeys from there. This is probably too early for Cabot to know the birds as Tacchinos and earlier than the 1524 date when they are first known in England but both men had all the right contacts. Cabot was sailing with funding and instructions from Henry VII, was Italian and also worked for the King of Spain. He may have come across Turkeys, not from Spain but from the New World and perhaps even recognised them and pounced on them as a desirable commodity or simply used Italian or Spanish contacts in Europe. I like to think that the chattering and gobbling of the new birds, inspired the Strickland to call them Talkies but, with his Yorkshire accent, everyone in London heard it as ‘Turkeys’. Dornt lissen tho, a dornt nor warram turkin abar.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The Aztec name for a male turkey, huexolotl, has been corrupted into the modern Mexican name Guajolote. Very different to Pavo or turkey but the name for a turkey hen was Totolin. The Aztec Turkey stew, totolmolli, seems to have survived as mole de guajolote. It’s just possible that Totolin, or a corruption made it to Cabot and Strickland via either Spanish sailors or traders familiar withy the Aztec original or some shared name origin with the Italian Tacchino. Tenuous, though it is, I would love it to be true. However it came about, the name turkey, both wild and domestic, returned to America and replaced any other pre-existing names north of the border with Mexico.

It was difficult to know where to start and it is equally difficult to know where to end. I’m far from finished but that’s quite enough turkey for me right now. [I’m stuffed or you must be stuffed]

Turkeys from Lifeforms Art

Well if you’ve read this far many congratulations! I just wanted to add at this point, we have Turkey T-shirts and Sweatshirts available.

We created the Turkey Sweatshirt as an alternative Christmas Sweater, we wanted to celebrate the magnificent wild turkey an all his colourful gobblishious glory – to revere him as the beautiful wild bird that he is, not steaming on a plate in the middle of a Christmas Feast!

The Turkey products are:

NOTES

The history of the Norfolk Black turkey

The ancestors of Norfolk Black turkeys were discovered in South America by the Spanish explorer Pedro Nino around the end of the 15th century. He traded them with Aztec Indians for glass beads, and brought them back to Europe.

Turkeys are believed to have first been brought to Britain in 1526 by Yorkshireman William Strickland.

Henry VIII was the first English king to enjoy black turkey, although Edward VII made it fashionable to eat it at Christmas. Indeed turkey was a luxury right up until the 1950s when refrigerators became commonplace.

They favoured drier conditions to be reared, so East Anglia became the main poultry-growing area. Many farmers in Norfolk liked and kept this bird, hence its name.

The Norfolk Black has developed over the centuries through selective breeding and is now recognised as English in origin. It was taken back to America in the 1600s where it was crossed with the Eastern Wild and from those matings came the Slate, Narragansett and Bronze breeds.

By 1720, about 250,000 turkeys were walked from Norfolk to the London markets in small flocks of 300-1000. They started in August and fed on stubble fields and feeding stations along the A12 road. Their feet were dipped in tar to protect them.

nAztec mythology, Chalchiuhtotolin (/tʃɑːltʃuːtoʊtoʊlin/;[stress?] Nahuatl for “Jade Turkey”) was a god of disease and plague. Chalchihuihtotolin, the Jewelled Fowl, Tezcatlipoca’s nahual. Chalchihuihtotolin is a symbol of powerful sorcery. Tezcatlipoca can tempt humans into self-destruction, but when he takes his turkey form he can also cleanse them of contamination, absolve them of guilt, and overcome their fate. In the tonalpohualli, Chalchihuihtotolin rules over day Tecpatl (Stone Knife) and over trecena 1-Atl (Water).[1]

The preceding thirteen days are ruled over by Xolotl. Chalchihuihtotolin has a particularly evil side to him. Even though he is shown with the customary green feathers, most codices show him bent over and with black/white eyes, which is a sign reserved for evil gods such as Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, and Xolotl. Another depiction of Chalchiuhtotolin’s evil side includes the sharp silver of his talons. His nahual is a turkey in which he terrorizes villages, bringing disease and sickness.