Wide Eyed Squids and Squid Kids – In search of the Kraken

Cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish, squid and nautiluses) are our most popular images at Lifeforms. In response to the popularity we decided to take it a little further.

I can claim no great expertise on the subject but a lifelong fascination does help prevent me from leaving the subject alone. My books about the subject give no list of species from UK waters. I found the vagueness of what I might actually find here, on a beach, frustrating. It is a clear sign that I am struggling when I find myself looking something up on the internet. However similar it may be to flicking through books, it is not something I enjoy. But, I was compelled to surf the web to get the information I wanted.

Who are our UK cephalopods?

Most of my books list two or three, but different twos and threes. I found some fisheries web pages that enlarged my list. And a recent, and timely, article in British Wildlife journal confirmed that we have at least 16 species visiting our waters. My list may not be complete, but I have produced a table of 26 species that can justifiably be called British.

I should say though, that some are rare and others are restricted to deep water. But nevertheless I take deep satisfaction from the fact that our islands are surrounded by cephalopod species. Having been lucky enough to find some of them while beachcombing and luckier still to snorkel with living animals, my experience adds up to 8 species in Britain and a few more abroad.

Aliens and monsters

I must admit that I was fascinated by depictions of Jules Verne’s giant squid attack and the engraving by Denys de Montfort, of a very octopus-like cephalopod pulling a ship down into a stormy sea. But, on the whole I cringe when people, even biologists, describe cephalopods as aliens, monsters or other-worldly even. Such descriptions are easy enough to find and, I suppose acceptable if we consider the ocean as another world and an alien environment to us. But we tend not to describe whales or giraffes or even man-eating tigers as monsters or aliens so why cephalopods?

They are earthlings, just like us, they belong on this World . And, if our behaviour towards each other is how we judge character, it is us who are the monsters and not our fellow beings the cephalopods. One things is certain, they are mind-boggling different to us and I quite like having my mind boggled by nature. Perhaps I was lucky. My introduction to cephalopods was through my children’s encyclopaedia and Jacques Cousteau. Only later did I encounter the science fiction mutations of these fascinating and exciting animals.

Grouping our cephalopods

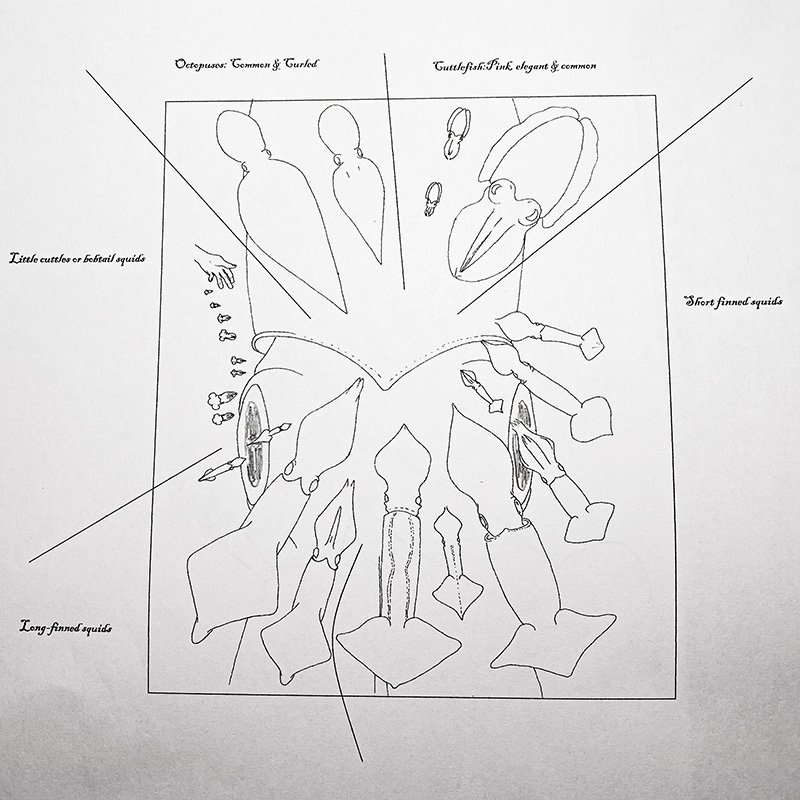

I think that the easiest way to start understanding our ‘native’ cephalopods is to look at them as groups. With a view to narrowing down later once that has sunk in. In reality, that’s about the stage I am at and I’m fairly content there!

I decided to draw outlines of UK species to get an idea of the sizes and shapes. As one of them is bigger than me and others are smaller than my thumb, scaling became a bit tricky. Slowly my diagram began to take the form of a clock that roughly divides the groups up, a bit like a pie chart.

So, very briefly we can group our cephalopods into two groups to start with. There are the decapods (meaning 10 footed) and the octopods (meaning 8 footed). Decapods include the cuttlefish and squids who have 8 arms plus two tentacles which can shoot out at speed to catch prey. Octopods, in our waters are represented by the fairly familiar octopus. As we only have one common species I can leave her there, beautiful as she is and look at the decapods.

The Decapods

This name is quite confusing as 10 limbed crustaceans, such as crabs, go by the same name. But, if you think of both humans and ostriches as ‘bipedal’ you quickly grasp that it is more of a description than a classification. The decapod cephalopods confuse it a bit more with slight of hand as there 9th & 10th limbs are often hidden or tricky to spot and might even be missing. So, shape is probably the better guide and especially with a living animal.

Cuttlefish

Cuttlefish are quite oval when viewed from above. There are 3 UK species but only one lives close to shore. They live near the seabed and can bury themselves in sand. But can also swim about (sometimes at high speed) like squid. They have an internal shell called a cuttlebone or sepion which makes the body quite rigid and helps control buoyancy. The cuttlebones wash up when their owners die after the breeding season. These can be used to identify their original owners. Their lifestyle is roughly half way between that of the octopus who likes to stroll and the squid who jets about.

The common cuttlefish, the one we are most likely to see is capable of spectacular colour and pattern changes but is most often dramatically tiger striped. Viewed from the side it is flatter than it is wide and these features, along with a W-shaped pupil, help set it apart from the squids. Its grasping tentacles with suckered clubs on the end can be retracted all the way into pockets a bit like torpedo tubes on a submarine.

Squid

Squids have more rounded pupils than cuttlefish. They can only retract their tentacles in to about the length of their arms. So they are never hidden completely. Our squids are long and tubular in shape more like a sausage or a carrot compared to the pastie, Weetabix or surf-board shape of the cuttlefish. Squid do not bury themselves in the sand. They are almost always suspended in the water like shoaling fish and they do shoal themselves. Whilst octopus and cuttlefish tend to meet up only to breed, squid are much more communal on the whole. They can live in vast shoals which are pursued by off shore fishing fleets.

Squid in UK waters can be divided into two groups; the short finned squids and, you guessed it, the long-finned squids. Our short-finned squids are often collectively known as flying squids. Some do leave the water and are capable of controlled gliding. It makes me happy to know that such things are going on in the seas surrounding our islands. It’s tricky to know which is front and back with a squid. The fins are positioned at the opposite end of the body from the arms mouth and eyes. But, if a squid were a ship, they are at the front or bow,as the pointy end precedes the rest of the body when travelling normally.

Short-finned squids have fins which form an arrow shape very much at the end of the body. Long finned squid have fins which form more of a rhomboid or diamond shape and reach a good way down the body. Most squid live in deep water during the day and rise to the surface at night to breed. Many of those I claim as British here are capable of vast migrations. Some species are found around the world. With their preference for deep water and long distance travel, squid are less diverse and less common in the southern part of the north sea. Which is shallow although some do migrate there. I’ll come back to squid in a moment!

Little cuttles or Bob tail squids

Lastly there are the little cuttles or bob tail squids which all look quite similar. Most live in deeper water but the delightful little Atlantic cuttle is possibly our most accessible cephalopod. As it can be found in the shallows on sandy beaches and sometimes turns up in children’s fishing nets. It is shorter bodied than the common cuttlefish and usually blotchy or spotty rather than stripey. They look about half-way between cuttlefish and octopus. They go through rapid combinations of spectacular colour change. But they won’t live long in your bucket as they need lots of oxygen and fairly stable water temperatures.

Oh, now to the elephant in the room and the subject of this blog…

The kraken wakes!

Some nature lovers lament a lack of diversity in British wildlife and travel abroad to get their fix of unusual sightings and experiences. I don’t think that way. The diversity of world wildlife is fascinating and spectacular and I would not want to downplay it. But I think there is plenty at home to keep a naturalist happy and busy for a lifetime. We have a diversity of insects, birds and mammals as well as the major reptile, amphibian and fish groups. Our invertebrates are the equivalent of a Serengeti in miniature beneath our feet.

For anyone looking for superlatives, we have some of the heaviest flying birds and birds of prey, some of the smallest mammals in our shrews and bats and much more. The leatherback turtle includes us within its natural range and is the largest of all turtles and tortoises. The ocean sunfish, a regular summer visitor, is the world’s largest bony fish. If that’s not enough the basking shark, the world’s second largest fish is a UK species too. The largest toothed whale is native to our water too and so is its prey.

The World’s largest invertebrate and the possessor of the largest eye in the known universe is native to UK waters.

It is, of course the giant squid, one of the most enigmatic creatures on Planet Earth. You may hasten to say that the (shorter but heavier) colossal squid now holds the title and it’s true. But, being pedantic, we don’t know if the largest giant squid was ever found and really I’m bunching them together here a little. The largest invertebrate is a squid, ours, in the UK, is the giant. Do look at colossus though…Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, it has glow in the dark eyes!

The Great British Squid

When I started drawing together information about native cephalopods, I felt a bit naughty considering the giant squid among them. It is rare and tends to be described as more oceanic and way out there in the sea than native. Nobody seems to claim it as ours or take responsibility for its well being but I think we should.

Famously owning very large eyes, I realised I might have difficulty illustrating a size comparison between the UK cephalopods that also included the giant squid. But I did feel I could line them up beside a giant squid eye. Which at 50 centimetres in diameter might look quite cool. I drew an oval, yep, a typical eye shape and then measured out the lengths of our other cephalopods to see how they might fit. I soon found that we have a lot of cephalopods! At least as migrants and some of them exceed 50 centimetres ,whilst others are much shorter than that. So, size-wise, the giant squid eye fits in quite nicely.

However, my imagined image of the UK cephalopod assemblage all more or less fitting within the eye of a giant squid was going to be a bit of a squeeze. After lot of sketching I decided, or fell into a world where the central part of the giant squid would create a background for the other cephalopod species. The draft I was working with had the eyes as depicted in many artists impressions; circular. But I remembered seeing footage of giant squid and that the eye was both fascinating and spooky.

So I returned to the internet to check it out. I have many pictures of giant squid in books. But they are all dead or artist’s impression and often at angles that do not tell me what I need to know. I wanted the eyes (and the rest of the giant) behind my UK cephalopods, to be as accurate as I was capable of. So I plunged myself, metaphorically speaking, into the depths of its world in an attempt to find out.

Perhaps the first scientific name I ever learned is one that we tend not to think of as a scientific name because it is so well known and iconic…Tyrannosaurus rex. It means King of the Tyrant lizards and sounds, when put like that, as much like a Dr Who monster as it does a complex and magnificent beast who’s giant footsteps we tread in on this little planet of ours. Sadly, that king is dead. Just impressive for me, is the living monarch of the giant brainy marine molluscs… Architeuthis dux.

WHAT DOES Architeuthis dux MEAN?

Giant squid are rarely encountered and are still very poorly understood. But squid science speculates that there may be 3 species of giant squid or more in the World’s oceans (all closely related) and the larger cousin, the colossal squid. Recent DNA analysis from around the world suggests just one Architeuthis species again. It would make this blog about ten times longer for me to go into all that (and I am seriously lacking both expertise and understanding) so I’m sticking with our own giant squid Architeuthis dux as, at best, a bystander.

Look into my eyes

Having said that, I actually fell at the first hurdle. In fact I stumbled over hurdles in one of those sporting bloopers everyone seems to find so amusing, but must be awful for the athlete. Luckily for me no one was watching. All I really wanted was a reliable reference of the eye of Architeuthis dux as it might appear in life. I could possibly have looked a little harder or paid for some less accessible material, but with the time and budget available, I failed. I could not find a picture of an eye of Architeuthis dux from the north Atlantic that gave me any real idea of the gaze of the living beast. The kraken waken not… Kraken still sleepen!

What I did find was that all the Architeuthids are widely considered to be very similar and possibly even sub-species of one species. So perhaps, their eyes heads and mantles; the bits I wanted, were indistinguishable. I’m not sure it is true but I had no choice but to look beyond the Atlantic at recent footage of live giant squid in the Atlantic; the same footage I referred to above. It was acquired by an international team. Who used historical records of giant squid to fix on the most likely spot in the ocean where they might actually encounter a living squid.

The results are a bit uncomfortable for the technophobe, but nonetheless spectacular images of this enigmatic marvel of the deep. Its eye is not round and is surrounded by furrows and folds. It looks old and wise and reminds me of the elephant eyes which are so striking in the last pages of Heathcote Williams book Sacred Elephant.

I took several sketches. I’m still in the blundering over hurdles stage here, because my idea of using the size of the giant squid eye as a 50cm scale for the other UK cephalopods wouldn’t work. Because most of the eye-ball is actually hidden under eyelid like folds. But, far from being fish-like or particularly squid like, the eye was more beautiful than I had remembered. It made the project feel significantly more exciting.

The Europeans

I returned to European specimens for the rest of the body. Most photographs of giant squid are taken either from a standing position looking at the specimen on the ground or are taken from an angle intended to make the squid look as big as possible. More scientific views giving a true idea of the comparative sizes of body parts are rare. Those of north Atlantic squid, rarer still. Luckily, and I should say I am very grateful to the thoughtfulness of the photographers or those instructing them, I found a couple of beauties.

One of the 1954 Ranheim specimen from Norway and the other of an actual British specimen, which washed up on South Beach in Scarborough in 1933. They are dorsal views and gave me a chance to map out the exact dimensions of the animals. Somebody went to some trouble to take the photos as they are not distorted by a fish eye lens and the photographer must have been some distance above the animals to get the shot.

Some crackin’ kraken tales

I am so tempted to wax lyrical about krakens here but will save it for another time. It’s worth noting though that cephalopods are a deep part of human culture. There are theories that humans are beachcombing apes, beachcombin’ fruit pickin’ apen is perhaps the truth and that our dispersal around the world was mostly by following the coastlines, only moving in land when we had to. I’m happy with that until evidence to the contrary washes up. The artists of ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean, even before the Greek and Roman expansions, were depicting cephalopods with respect and as beautiful creatures, and the culture has continued to this day.

The Krake

Tales of giant cephalopods, or beings that might be they, go back at least to the writings of Homer (in the Odyssey) and Pliny. The Kraken itself is closer to home having emerged from Norwegian literature and tales from the sea. Krake, appears to be the word origin with the n added to denote the definite article… The Krake. The earliest known description dates to 1555. Much later than the Viking sagas and a bit disappointing really. In his book, Kingdom of the Octopus, Frank W. Lane leads me to believe that Krake derived from the name for a stunted tree so, I guess, a many branched tree of the sea. Considering that both elephants and trees have trunks, that sounds about right.

What I like is that scientists were sceptical about all this but still interested. Linnaeus put Kraken into his first edition of Systema Naturae (1758), the basis for the scientific naming system we all use to this day. He names it Sepia microcosmos but removed it from the later editions. Perhaps he believed the tales but without any specimen, felt a bit silly in front of his peers.

Science and literature collided in an apparition of spray and wreckage like ships lashed together in a stormy sea. It has perhaps always been like this and always will be and what fun and confusion it causes. In 1805, in a colossal publication about molluscs with a fairly colossal French name, Denys de Montfort introduced the Poulpe Colossal. Which he said wrapped its tentacles around the masts of ships to drag them to the bottom. He was not taken very seriously by either scientists or mariners but his engraving was and is an all time favourite that struck the minds of other story tellers such as Victor Hugo (Toilers of the Sea, 1866) and Jules Verne (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, 1869-70). But these monumental authors had other encouragement in the meantime.

I do believe in Kraken, I do, I do; take me to your leader

Starting with accounts of a specimen washed up in the Oresund, Danish Scientist Japetus Steenstrup (a giant in cephalopod taxonomy and a squid kid) looked at old records of large stranded cephalopods. He examined the all remains he could find in museum stores. Taking on the myths of kraken and sea monk together, he was able to produce evidence that Kraken really did exist. And that was without evidence they had missed in the library of the royal Dublin Society from 1673. A beast washed up in Dingle bay, that was the size of a horse, with the jaws of an eagle and eyes as large as a pewter dish. It was in 1857 that Steenstrup named it Architeuthis.

Archi means great or most important and teuthis means squid. In my mind, Steenstrup slayed the kraken and debunked the sea monk but freed the giant squid. The driving force for him was a preserved giant squid beak in a jar. He knew his cephalopods and he knew that this one was from a giant. He was a meticulous biologist and gathered specimens and information from around the world by talking to sea captains in the Copenhagen docks. I think it was at this point, across the various genres of humanity: science, mythology, maritime stories and observations, that the Kraken awoke.

Certain of its existence beyond any doubt at all, Steenstrup gave Architeuthis the species name ‘dux’ which is Latin for leader. So, just as T. rex is King of the tyrant lizards, A. dux is leader of the great squids. How cool is that? But there’s a little bit more… the great squid was named nearly 50 years before the tyrant lizard and lives on today.

Did you just see what I saw?

In 1861 Lieutenant Bouyer of the French warship Alecton reported to the Ministry of Marine an encounter off the Canary islands with in his words… “a monstrous creature which I recognised the “Giant Octopus”, the disputed existence of which seems to have been relegated to the realms of fable.” The crew spent 3 hours trying to catch the animal but eventually relented for fear of losing their lives to it. This incident is said to have inspired Jules Verne’s depiction of the squid battling Captain Nimo’s submarine Nautilus according to Frank Lane.

3 Wide-eyed men in a tub; or 2 men and a squid kid

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

From the Kraken by Alfred Lord Tennyson

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

In 1873 3 men in a boat, or two men and a 12 year old boy to be more accurate bumped into a giant squid in Portugal Cove Newfoundland. Investigating it they lunged at it with a boat hook. Which, according to their story, resulted in the previously life-less mass rearing up and grabbing hold of their boat.

They noted its huge eyes but theirs were probably pretty wide too ,as they believed it was dragging them down into the water. The two men were paralysed with fear. But the boy, Tom Piccot by name, grabbed a tomahawk from the bottom of the boat and chopped at the offending arm and tentacle. The squid ejected ink and departed. But Tom (an accidental squid-kid) had a trophy, a 19 foot long tentacle (apparently not the whole thing which was longer still). Which was bought by a local clergyman the Reverend Moses Harvey. Harvey interviewed the men (still apparently in shock) straight afterwards to get a clear story.

But less than a month later, had more luck when four fishermen caught a complete animal in a herring net in Logy Bay not far from the previous encounter. Harvey rushed to the scene and paid for the specimen which he draped over his sponge bath for a photograph. Perhaps the most famous squid photograph ever taken. The specimen corroborated Steenstrup’s work and, in Frank Lane’s words, “proved beyond doubt that Krakens exist , that they are giant squids, and that they are the largest invertebrates on earth.” They have of course, famously been supplanted from that title by the colossal squid.

In 1878, Harvey acquired yet another local specimen which he sent to Professor Addison Emery Verrill, a molluscan specialist (a squid kid) at Yale University. He named it Architeuthis harveyi after the clergyman, clearly accepting Steenstrup’s work, but the name has since been superseded in accordance with the strict rules of nomenclature. Steenstrup’s original name, Architeuthis dux remains the name of our kraken. Verrill’s 1881 publication convinced the world of science, once and for all time, that giant squids exist even though the evidence had been lying around for some time. The kraken dozed!

3 men in a tub and a dozing kraken on cue!

More squid turned up in Newfoundland waters but in 1875, another 3 men in a boat, a curragh no less, off the coast of Connemara in Ireland came across the largest giant squid recorded “basking” on the surface of the sea. After a battle with knives and a pursuit 5 miles out into the Atlantic in their little round rowing boat, they managed to wrestle its body, dismembered from the mantle, aboard with them. They must have settled much lower into the water. Once ashore the two tentacles were found to be 30 feet long with the arms measuring 8 feet. The head, without its appendages, weighed 6 stone and the eye had a diameter of 15 inches.

Kraken dozens and half dozens

Since then at least half a dozen giant squid have turned up on the west coast and Ireland and over a dozen in Scottish waters, plus a couple at Either end of England, Scarborough and Penzance. Perhaps the lagoon-like nature of the North sea and Irish seas coupled with a lack of sufficiently deep water, restricts Architeuthis to areas close to deep ocean and it may undertake long migrations which are loosely defined for us by these rare occurrences.

Waken the kraken – bringing the dead back to life

So, back to those photos. The Ranheim specimen was in surprisingly good condition but still sunken and collapsed and gave me no real idea of the eye as viewed from above. The Scarborough specimen was no better. Beach visitors had apparently been jumping up and down on it before it could be secured and preserved. One eye appears to be missing and the other is not really visible due to lighting and deterioration but I got enough idea of the head shape to patch together an impression of what I think the eye looked like from above.

My first boss, in my first week at work as a trainee taxidermist, took me out on the back of his motorbike clutching a cinema screen, to one of his talks about his museum work. He played to the children’s curiosity better than any teacher I’d ever known and, showing them the selection of glass eyes used for taxidermy specimens, he asked them what animal they thought, has the largest eye in the world. Hands shot up excitedly.

“An elephant” shouted one.

“No, but I understand why you think that.”

“A whale” said another, asking rather than telling.

Hands fell down as the class realised it was harder than they thought.

“A Giraffe” yelled a child as it suddenly came to her, thinking no doubt of big animals with noticeably big eyes.

“You’re getting closer and further away at the same time.” Said my boss. “Giraffe is a good guess. It has the largest eye of any mammal but another, more feathery animal has a bigger…”

“Ostrich!” called out a voice as if his life depended on it.

“I’ll give you that” said my boss. The ostrich has the largest eye of any land living animal and it is the largest eye that I can get made in glass. But I’ll give this glass fox eye to anyone who can tell me what animal has the largest eye of all, in the whole animal kingdom.”

After many guesses and many clues, one delighted, wide-eyed little boy (another squid-kid) won the fox eye with a big beam on his face.

Jeepers Creepers, why such big bleepers?

But you have to wonder why the eye is so big, on squids rather than kids that is. I never really bought the theory that the eyes were big to see prey in the gloom of the deep. Tigers, killer whales, polar bears and sharks don’t have giant eyes. Nor do wolves, eagles or piranhas really. There are some exceptions such as owls, mantids and jumping spiders but mostly, the wide eyed look of the comedy thriller film is the look of a victim or someone in a coracle a mile out to sea who just woke a kraken with the prod of a sharp point. Recent research indicates that this is true. The giant eyes of giant squid are probably more to avoid getting too close to predators than they are for finding a meal.

And what a predator they face… Moby Dick. The kraken shakes!

Perhaps before I go on I should return to the wonderful enigma that the giant squid currently is. We know no more about than we do about the cave painters of Lascaux. They are earthlings, shrouded in mystery who have given us snippets of information about themselves.

There is very little information about the part of the ocean they actually prefer, what they really eat, how fast and aggressive they are and how they breed. All other squid are very fast indeed and are voracious predators.

Dissections of Architeuthis specimens reveal that they have comparatively weak musculature and some signs of cannibalism. The fact they only tend to be caught singly (when they’re caught) is considered to be a sign that they live solitary lives (unlike many other squid). I am happy to accept that such a large predator (with cannibalistic tendencies) may live a solitary life. It’s possible though that they form larger shoals, packs even, and are simply too evasive to be caught by trawlers etc unless they have been disabled. Perhaps they congregate to breed and it is then that they are vulnerable. I think that the apparently weak muscles is true of other large species such as giraffes and elephants which don’t have the benefit of the support of water and yet are still very strong and fast.

We’re lead to believe by some literature, that giant squid are relatively slow ambush predators who wait for prey to come within reach and perhaps hang in the water column waiting for prey to touch their arms which are thrown out like a spider’s web. When they feel something the long tentacles shoot out to grab it.

Giant predators

I’m not completely convinced by all this. Giant squid are giant predators like tigers and bears and great white sharks. I feel they are adapted to hunt large prey. They show no sign of moving to planktonic or comparatively smaller prey. The clubs on the ends of the tentacles are long compared to many other cephalopods. The tentacles themselves (like the arms) are long too and are capable of locking together like a zip. Length, as in a rope or a boa constrictor, can increase strength for the purpose of subduing a victim. The suction disks allow squid to grab prey of a similar size to themselves. They are not really suited to very small prey. This leads me, perhaps fancifully, to think that giant squid can cruise at high speed, but also have a very long reach.

I can imagine their long tentacles shooting into a shoal of tuna, grabbing one with the long clubs and pulling it close into the long arms, wrapping it up and quickly subduing it with a bite from the beak. It is possible they eat only the meat and so no bones or even scales remain as evidence from these large meals. A loss of tuna, and other large fish from coastal waters would coincide with a reduction in sightings of their predators too. It’s only a theory, with very little evidence, but I’m inclined to think that giant squid specialise in big game fish.

Back to Moby

One thing is for sure. Giant squid are preyed on by sperm whales; they’re famous for it. Sperm whales hunt other prey too but part of their unique appearance may be owed to adaptations to hunt giant squid. This suggests to me that giant squid were not always rare and solitary animals even if they are more like that today. If Moby is partly adapted for giant squid hunting then it must be a prey worth catching; numerous enough to be worthwhile.

Giant squid are no match, in strength for sperm whales. But little is known about the toxicity of their bite or their speed or ability to out manoeuvre the whale. Sperm whales are relatively easy to catch when pursued by harpoon ships and so may be no match for even a fairly slow squid hampered by giantism and scaled down muscles. I did read a theory that the giant melon of the sperm whale’s head could be a squid-kit that create a sonic beam to stun giant squid… why not?

All I can really tell you is that it is a fascinating enigma and there is much waiting to be learned.

A perfectionist creates art!

I found that there are plenty of other squid in our waters. When pulled together, they take up quite a bit more space than one giant squid eye. So, in order to show the body around the eyes I had to look more closely at the rest of Architeuthis. Idecided, in order to get the shading right too, it would be easiest to build a plasticine model to work from. This took me a step further into giant squid study and obsession, as you can see!

Having completed the clock after weeks of research and stippling, I felt that I owed the giant squid a piece of his own. I moved to colour for this piece to show what a beautiful creature the giant squid really is. I hope I’ve done him justice.

I like to think that Tennyson felt that we should not disturb the Kraken’s home for it’s sake and ours. John Wyndham seems to feel the same in his apocalyptic science fiction novel, The Kraken Wakes; although his kraken is not our kraken. The more we learn about the ocean, the more we find out about the damage we have done and continue to wreak across the kraken’s world.

Kraken keepen waken me up at night

The Kraken

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Alfred Lord Tennyson – 1809-1892

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge sea worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die