It’s too late for the Steller’s Sea Cow… I guess that’s its message.

Whilst many people, most of them sailors, saw, hunted and tasted Steller’s sea cow, it bears the name Steller simply because Georg Wilhelm Steller was the only person to describe the animal and its ecology scientifically. Related to the much smaller tropical manatees and dugong’s, their giant polar relative was extinct within 30 years of its scientific discovery. Such A terrible shame and it was more rapid than the demise of the much more publicised dodo or the great auk. Was it a wasted existence or does Steller’s sea cow have something more for us?

Lessons to be learned

For me, for us here at Lifeforms, it has importance and it has a lesson for us. Islands are considered to be intense natural workshops of evolution and Steller’s sea cows could be argued as an island species but, being an aquatic animal living in the Pacific Ocean, I like to think they had more options than the Dodo which could not fly or swim.

The Pacific takes up more of our planet’s surface than anything else and yet it didn’t have enough space for the sea cow to hide.

There are many things important to science in the sea cow’s biology and story but, for me it is two things in particular.

- Firstly that these giant swimming animals had taken the evolutionary path, not to swim far, but to hide from the harsh ocean in sheltered bays and inlets, instead of sifting the ocean for high protein foods as whales and the largest of sharks do. The sea cow’s closest relatives, the dugong and manatee are small by comparison and it is easier to understand them as river and estuarine species tucked away in specialist niches but Steller’s Sea Cow was a giant. Whales roam far, polar bears roam far, elephants roam far but Steller’s sea cow was like an elephant hiding in a cherry tree. It was once much more widespread but not a roamer and I like that and find it interesting.

- The second point for me is you really! By ‘you’ I mean all of us interested in wildlife and its preservation. One man decided to make detailed records of this particular animal for science. There is nothing complicated about the records, they make an easy read and an interesting one. Without Steller’s work I think his Sea Cow would be a very obscure foot note in the list of extinctions. Without Steller and the shipwreck the sea cow might have slipped into extinction unknown to science and presumed to be prehistoric. That’s a pretty big thing to go unnoticed and it shows that we could easily miss lots of smaller species say in rain forest valleys for instance. Another person noticed Steller’s sea cows, a Russian geologist called Jakovlev or Yakovlev, he noticed they were disappearing fast and mostly as stored meat in the holds of ships. His argument, which was strongly worded, seems to have been to preserve a resource for long trips rather than a fellow creature, but if his words were heeded the Sea cow might have survived. So I think it is important to study species no matter how common they may seem and record what we find.

The Steller’s sea cow’s lesson, for me is this. Extinction happens, it happens at the hand of man. We see lots of stories on the TV and in books and magazines about threatened species and many have some kind of positive spin. We learn of the threat, we feel the peril the species is in and then we breathe a sigh of relief when we see one person is doing something. Don’t take it for granted they are doing enough. I’m not suggesting you should interfere in their work but if you can find a way to support then I say, “do.” And, anything you can do at home or school or locally should be done as a knock on effect of the Steller’s sea cow story.

Read its story, it might make you cry, but use it to understand that other species teeter on the brink and our energy should go to preventing that. Bumblebees, nightingales, turtle doves, crayfish, mud snails, the list is almost endless and many of them could be saved by gardening in a certain way, being less wasteful, driving less, refusing plastic packaging, using less electricity and water etc etc etc. For me, we’ve learned our lesson now, the sea cow is part of that lesson, it can live on in the memories passed to us by Georg Steller but let’s look after the rest of our fellow species.

Why did we choose the Sea Cow?

So, anyway… I first came across the Steller’s sea cow in a book called Searching for Hidden Animals by Roy Mackal. At first I couldn’t believe it and had to read the passage again. I love diversity of form. Of fish, it’s the seahorse that fascinates me, of all the birds I like the penguin, of mammals amongst my favourites are bats and whales. Also – I love the sea cows, they are extraordinary vegetarians and are often considered to be the source of mermaid stories.

Well here in a book that claimed there might still be trilobites and yeti about was a tale of a giant sea cow from historical times. Since then, I think I was about 18, I have looked out for information about Steller’s sea cows and been keen to reconstruct one. It was our three sons, Jake George and Ben however who insisted that our next extinct species should be this beautiful animal. We have decided to concentrate primarily on marine life this year. We worked on the Great Auk because it was globally extinct, British and we have direct experience with it. Now we have moved onto Steller’s sea cow simply because we think it is an amazing, seldom told story of the largest marine animal to become extinct in historical times. Read it and weep!

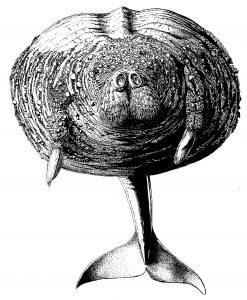

To make the illustrations I decided not to work from anyone else’s interpretations, but from Steller’s own descriptions and measurements. Most make sense to me but some are a little difficult to interpret due to terminology, translation or missing in-between measurements. I began with a photograph of a skeleton to make an outline and then drew in Steller’s own observations. Where information was missing (hardly at all as it turned out) I referred back to the closest living relative the dugong. I used an x-ray picture of a dugong’s head to work out the most likely depth of tissue between skin and bone to produce as accurate a picture as I am capable of doing.

It was so fascinating and so absorbing I think I could spend the rest of my life just drawing Steller’s sea cows! I’m not a fan of my own work but the result, especially the face, feels like a message from the past… Carpe diem!!

Georg Steller

In 1741 in an ill-fated voyage Georg Steller found himself shipwrecked in the north pacific. He was the ship’s physician. Steller had made an epic journey across Russia and Siberia only to make another Epic journey further eastwards with Captain Bering after whom Bering island and the Bering Straits are named (and even Beringia). Bering died on the expedition, most of the crew died and were shipwrecked on … Bering island.

They built mud huts and attempted to repair the ship. It took 10 months to make something seaworthy. In that time, albeit a frustrating time for many reasons, Steller, who was a passionate naturalist and meticulous scientist, spent an enviable time watching and studying what he called ‘manatee’.

He walked into the water and touched them, he watched their behaviour from the door of his hut and he studied their dead bodies on the beach. Steller was a straight talker and it seems it got him into trouble so he never actually made it home or published his account. However his prolific studies were published posthumously and in it is his fascinating and heart-rending account of the sea cow that bears his name. In Steller’s notes we read that sea cows lived in family groups and protected each other. They spent much of their time grazing sea weeds in the shallows and looked from a distance like upturned boats with half their body always out of the water.

Bibliography and Further reading

There is lots of information on-line but my favourite references (if a little dated) are…

Searching for hidden Animals: An Inquiry into Zoological Mysteries by Roy P. Mackal, Cadogan Books. 1983

The Auk, the Dodo and the oryx: vanished and vanishing creatures by Robert Silverberg, Worlds Work ltd. 1969

Steller’s Island: Adventures of a Pioneer Naturalist In Alaska by Dean Littlepage, The Mountaineer Books 2006

De Bestiis Marinis, or, The Beasts of the Sea (1751) Georg Wilhelm Steller , Walter Miller (Translator) Jennie Emerson Miller (Translator) Paul Royster (Transcriber and editor) available as a downloadable pdf from :http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience.