Are we surrounded by sharks?

Sharks in our consciousness

If you live inland and especially in the British Isles, you probably have little reason to think about sharks. That doesn’t mean you don’t think about them, just that you don’t have to. I read a statistic from the 1980s saying that, at any one time, there are several thousand people floating in the ocean, estranged from the boat they set out in. Whilst most bathers don’t need to think about sharks either, further out to sea they float up to the top of the agenda. Especially in tropical waters.

Either way, it is difficult to think about sharks without thinking about Jaws, their jaws, shark attack and dorsal fins. Sharks are notorious for revealing themselves when their dorsal fins protrude through the surface. It is about as iconic as threats from nature can get, more so than the jaws themselves. Imagine if our thoughts had dorsal fins which protruded through our heads!

Shark Week

It’s shark week as I’m writing this and we have new shark products to celebrate. Not all will be ready this week, but shark are worth celebrating at any time. We’ve focused on the amazing British sharks. I’ll share more about the individual species at a later date. This is really an appreciation of sharks – read on to find out more.

The shark monsters

In Britain, we have no lions, tigers, bears, leopards or large aggressive herbivores like wild bulls, hippos and elephants. With the possible exception of dogs, we are largely used to this absence. Venomous snakes, spiders and scorpions are rarely in our path. Bees and wasps generally prefer to avoid us but do like our self-indulgent treats. That is probably why we think more about sharks than most of us need to. Out and about, we see children and grown ups wearing shark pictures. Usually they are fierce looking, mouth open, raaaaaaaaaaaar!! We can’t see far into the sea so maybe, just maybe, beneath the surface is the ogre we need to complete our life. Our need to have an enemy. So, are they there?

The answer, as you probably know, is yes. There are sharks all round the British Isles. Are there people-eating sharks around the British Isles? Again the answer is yes but don’t come out of the water just yet unlkess you’re shivering with cold. You’re more in danger from sewage, bravado and stupidity than from man-eating sharks. I could argue that, in the literal sense, man-eating sharks don’t exist at all! Yes, people have been eaten, and partially eaten by sharks and they, with my heartfelt sympathy, would surely disagree. But here’s my point. There are crab-eating macaques, crab-eating seals (which eat krill more than crabs). There are monkey-eating eagles and snake-eating snakes all adapted to hunting particular prey. No sharks are adapted to preying on humans. And so I rest my case that man-eating sharks don’t exist.

Man eating sausage

However, if you slip a meat sausage in among the vegan sausages in a ready meal or a buffet, there is a good chance it will be eaten or severely damaged beyond repair, by the teeth of a hungry vegan, who was in no way looking for a meaty sausage. Similarly, a meat lover, faced with a sea of meat-free food might spot the one meaty morsal available. Then gobble it down, because it is the only available prey at the time. Such is the curse of the shark. It is doubly cursed, it occasionally happens to eat people placing it among the enemies of mankind. It is a perfect target for hunters looking for an enemy to make a trophy of.

Sharks of the World versus sharks of Britain

Great whites, whale sharks, tiger sharks and the notorious bull sharks loom large in the world of sharks. The famous and infamous great white is listed in my childhood encyclopaedia as just ‘white shark’. I was not aware of its greatness until Jaws splashed all over the book shelves. Then onto the great silver screen to become, I believe, the first “blockbuster movie”.

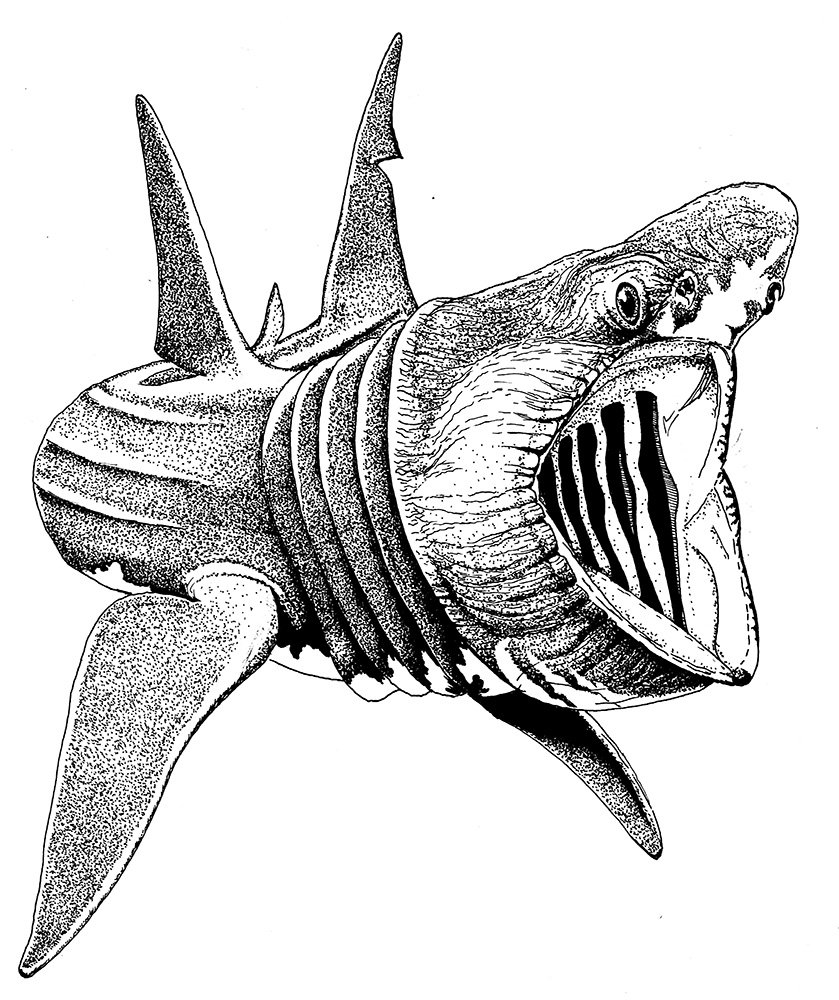

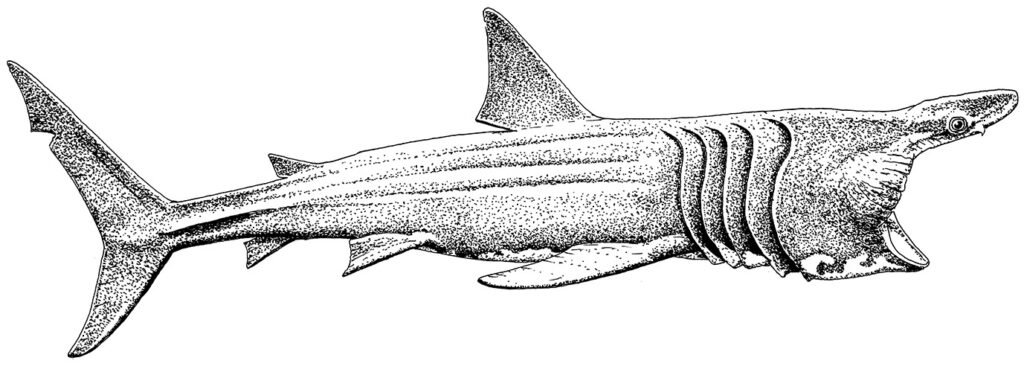

The whale shark, the world’s largest fish, arguably producing the world’s largest egg but probably never ‘laying’ it is a harmless plankton feeder on many a diver’s bucket list. Stripy tiger sharks would be considered giants if it weren’t for the other two and are much more likely to gobble you up. The bull shark, also known as the Zambezi shark is widely considered to be the most dangerous shark of all and it will venture into fresh water. I’m not much more than a layman where sharks are concerned. But there are a few more names that the layperson might know. Hammerhead of course, mako, basking shark, thresher and blue spring to mind. One significant difference between these and the white, tiger, bull and whale sharks is that they do venture into British waters. Braving cooler temperatures and shallower continental shelf waters.

Now, I have a keen interest in all world wildlife but my interest is much stronger in those species which are native to where I live. Those more accessible species are part of my world and I can argue that I am part of theirs and in a good way, rather than as an intruder or enemy.

Are British sharks worth the bother?

So what of British sharks? Most of us know of great whites and tiger sharks and such species, exciting as they are, make it onto our TV screens but are they British? Are British sharks worth bothering with; aren’t sharks of the World more interesting and exciting? I say yes; yes, yes, yes. British sharks are your sharks, my sharks, our sharks, and we are their humans. Perhaps I should re-phrase that. British sharks are at our mercy and in our care. As a life-long conservationist, I believe that the best route to world conservation, is to set an example at home. If you are anything like me, once you get into conservation at home, you don’t want to be anywhere else. Many people dream of Oz, but, as Dorothy said, there’s no place like home.

Hic sunt loca… here are sharks

Whilst many of us living inland may feel like landlubbers, with no real connection to the sea, if you live in these islands, you’re an islander. Being an islander comes with a background sense of certainty. We have natural and fairly effective borders and collectively own the land within them. We are also quietly conscious that there is more to Britain than territory, soil, rocks and trees. There is the sea around us. Paying just a little more attention to it, we find it to be consistently one of the richest fisheries on the planet. That’s something to celebrate and to conserve and these words are part of that celebration. I love one liners.

One of the most persistent and famous one liners (relating to nature at least) is written on the Lenox Globe of the early 1500s… “Hic svnt dracones” or “Here are dragons.” It relates to a far off land on the edge, or more likely off the edge, of the known world at the time. Such maps lit up the adventurous side of those who saw them and continue to do so today. But I’d like to re-draw the Lenox Globe or perhaps the Mappa Mundi for school children today and scrawl across our corner of the Atlantic… “Here are sharks” if only to encourage more people to grow up caring about the nature that is around them.

There’s no place like home!

Rather than following the yellow brick sky (full of polluting jet trails) to Oz for a shark cage experience hanging off the side of a motor boat. Yes, world wildlife and the world of sharks is great and as important as any other but, for me, as Dorothy discovered, there’s no place like home. That’s my tribal link, I’m no nationalist, but I’m joined to my land and its own natural wonders. So what of our sharks?

Our British Sharks

Let’s dive in… oh, but wait, wait, wait! Before we do, is it safe? Perhaps we should consider shark attack first.

You may find yourself shouting “whaaaaaat!?” at this next line but it is food for thought. There are probably 3 types of event that can be called shark attacks.

Attacks by people on sharks – commonest

Provoked attacks by sharks on people – second most common

Unprovoked attacks by sharks on people – least common

I am not very up to date on this. My last reading frenzy on shark attack was a horribly gruesome book called Jaws of Death by Xavier Maniguet, subtitled Shark as predator man as prey. It’s cover bears a warning about its disturbing photographs. They really are nasty, but the text is the work of a naturalist trying to help the world of people understand the needs of a marine predator.

It is possible to read this book without looking at the photographs; you could even tear them out. He does use some terms, such as ‘monster’ that I’m not happy with but it was written in the 1980s and he’s French so I’ll excuse it. And, if you’ve been bitten and are facing the open jaws of and inevitable second bite, the shark is the monster. In fact if monsters and dragons are fable (monstra non sunt hic!), then the nearest thing we have to monsters, in British waters, are sharks.

Cut along the dotted line and take this on your tropical holiday or don’t go…

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Xavier looks at the facts.

- Firstly I can reassure you that the only attack in British waters, the ‘World’s most northerly shark attack’ on record was provoked. It barely registers as an attack. It was a fisherman catching a thresher shark being bitten on the arm as the poor thing fought, in vain, for its life. That was in 1960.

- Xavier points out that sharks are much more dangerous out at sea (i.e. shipwreck victims and oceanic cruise pleasure swims) than they are in coastal waters

- Of course, coastal attacks do happen but they are restricted to certain regions and often certain beaches and certain parts of those beaches where there are protection measures in place.

- He states that sharks are much more attracted to bare skin, as is the much more voracious killer, UV from the tropical sun.

- They tend to attack a single victim. Multiple victims are often lacerations caused by fins or bites when a rescuer gets between the shark and its victim.

- Sharks are attracted to shiny objects, noise, fishy or other prey-like smells and noise.

- They are attracted to yellow or orange.

- They tend to circle before attack – if you can get out, now’s the time to do it!

- Repelling sharks is a complicated subject as different repellents work for some species, but really don’t work for others. Some sharks are repelled by acetic acid or chemicals contained in shampoos, but most quickly wash away anyway. Beating the water, or the actual shark that’s too close for comfort are recommended. But be sure to do it confidently and firmly rather than flailing like an injured seal.

- An interesting feature he examines is the apparent immunity of certain species of sole to shark attacks. These fish had never been found in the stomach of a shark. The cause is narrowed down to pardaxin and other secretions that irritate shark gills.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Now I’ve got you started you can find out for yourself, either in Xavier’s book or from modern equivalents or online.

Shark attack or sharks attacked?

The bottom line is that shark attacks are very rare and almost impossible if guidelines are followed.

Sharks are sometimes described as killing machines or monsters. But really they are highly adapted predators suited to certain marine habitats and prey. We are not their natural prey.

Our effect on sharks is far greater. Many species are being driven towards extinction. Recreational swimming is a relatively new thing, and sharks are not the most dangerous aspect of that activity. Whilst they have probably been following traditional migration routes to feeding areas on the world’s coasts for millennia and more. Now, not only are they persecuted directly, but the world’s most sharky beaches (presumably the best and most important beaches for anyone who is a shark) are netted off for bather’s safety or have suffered over-fishing. They also face the established threats to marine life such as pollution, global warming, reduced prey through pressures on fisheries (not a term the inhabitants of the sea would use for themselves) and their own part in that as targeted fishery species and by-catch. Noble hunters are pretty much knobbled on Planet Earth.

Dangerous to humans

Of the 343 or so species of shark in the world, 31 are considered dangerous to humans. There’s no getting away from the potential danger. But there are ways of avoiding it and looking out for warning signs. So, despite the tragedies, it’s pretty much up to us to avoid attack. Over 74 species of shark are classified as either vulnerable or endangered including many from our waters. As well as iconic exotic giants like the thrilling great white, the bizarre great hammerhead and the magnificent whale shark. An estimated 100 million sharks are killed by humans annually, whilst the average for shark attacks on humans runs at about 4.3 people according to the International Shark Attack File. When it happens, it is much bigger news than melanomas from sun damage, car and boating accidents, misadventures while swimming etc. Let’s give sharks a break.

Sharks at home

Since we launched Lifeforms Art we are regularly asked if we have pictures of species we haven’t drawn yet. “Have you got anything with sharks on” became a regular request. For the reasons stated above we didn’t want to do what we’ve seen so many times… random world sharks. We wanted to introduce people local to us, to our shared local shark fauna. I think it gives us all a greater appreciation of our surrounding seas and the wonders they hold.

World wonders – the shark’s world

…And speaking of wonders, what wonders sharks are. Let’s dwell on sharks in general for a while. They are often described as killing machines and primitive but this very much over-simplifies and really degrades what Jacques Cousteau dubbed the splendid savage of the sea.

Sharks have evolved and adapted alongside everything else. While they carry some ancient features, preserved for their usefulness from prehistoric ancestors (we too, have held on to such feature as ears, teeth and digits), they are very much an up to date fish in my opinion. Classed as cartilaginous fish, as opposed to the ‘more modern’ bony fish or teleosts, sharks stand up to comparisons pretty well. Among the most modern (recently evolved into their present form) of bony fish is another of our favourites, the seahorse. Seahorses have a more limited distribution than sharks, a limited, albeit specialised, way of feeding and just over 30 species compared to shark’s 340 plus species.

Sharks may have their problems, but they seem much more likely to stick around than the vulnerable seahorses. If superlatives are your thing, let’s take size. The largest of the bony fishes, the ocean sunfish, can measure a whopping 3 metres from fin tip to fin tip. At least 24 shark species regularly exceed 3 metres in length and some reach more than double that size. I do not seek to demean sunfish, seahorses or bony fish in general, I love them. But sharks are still big players in life on earth and are keeping up quite nicely.

Killing Machines

Killing machine grinds on me quite a lot. Sharks do not need a programmer and are not mechanical. They can solve problems and they can learn. I prefer to think of them more as living technological wizardry (self-made of course). The typical things we learn are that sharks can smell a drop of blood in a million (or whatever) drops of water. And, with no further ado, follow the trail of blood, like blood hounds to the bleeder and CHOMP. Sharks do so much more than sniffing and chomping although they’re good at those things too.

Can sharks hear?

Sharks may not possess the big floppy ears of a blood hound or the upright ones of a rabbit but their hearing is spectacularly good. It is sound and not the smell of blood that tends to attract sharks to ship wrecks. They cannot, I’m told, hear many of the high pitched sounds that we can but, in the low register, they hear things that we cannot. This includes the sound of struggling fish, or anything struggling really.

We simply don’t hear the underwater sounds that sharks pick up. As Xavier says, “this explains why sharks frequently appear, coming from any direction, after a fish has been harpooned or caught on a line.” Fishing lines and anchor ropes and chains, in a current, also make a noise that’s attractive to sharks. Like the long slow twang of a cello string or piano chord… ‘snack bar open’, there’s bound to be something I’ll like.

So, anchoring a boat to go for a swim in tropical waters, and especially in places where sharks are known to have attacked, can be asking for trouble. Just as swimming around with a living fish impaled and struggling on a harpoon is calling predators in. An interesting phenomenon, according to Xavier, is that many sharks, attracted by sounds will flee if the noise suddenly increases once they are up close. So, correctly used, their hearing abilities may be used to create a deterrent. The most observant of people, are really getting to know sharks.

Sound travels faster through water

Sound travels faster and farther through water than it does through air. At room temperature sound travels at about 344 metres per second and a leisurely 330 metres per second below zero Celcius. That’s about 740 miles per hour. Underwater sound travels at more than twice the speed… 1500 metres per second, and can be heard by sharks many thousands of metres away almost instantaneously. If 740 mph sounds fast, try 3,355mph as the clunk of an anchor and the harmony of the mooring line call the hungry in for a potential meal. Fortunately, however curious, most sharks don’t see us as food. They are adapted to particular prey and cautious of unusual beings. They will at least take their time before testing the unknown. Others have already learned to keep their distance and steer clear.

The smell of the ocean

Hearing is an immediate thing. Smells can carry much further, but over a longer period of time. So the two attractants compete under different circumstances, because the source of a delicious smell may have long since ceased struggling ,whilst an aroma of a recently injured ‘victim’ may take time to drift into sniffing range or drift off in any direction other than the right one. Nevertheless, in the absence of sound, smell may alert a shark to something interesting that could be more than a mile away although usually much closer.

One drop of blood in 100 million drops of water is all a shark needs to think that something delicious is within an easy swim and worth taking the trouble to sniff out. Shark nostrils are worth a closer look. Be careful with this advice as looking closely at shark nostrils could cost you your head. I reiterate, it’s usually your fault if you get bitten!

Shark Nostrils

The nostril effectively has an inlet and on outlet. Two holes per nostril which direct the flow of water over internal folds to analyse its chemical contents far, far better than we can with air. The form of the nostril means that water does not flow into the mouth like ours and is separate from breathing. The shark does not need to sniff but, as it swims, has a constant stream of water flowing over its sensors. Here, the tastes of the shark are interesting, as some sharks were found to be 4 times more sensitive to the smell of tuna blood than they were to blood of mammals.

Albert Tester (an appropriate name) discovered that lemon sharks that are hungry could detect one drop of tunny blood in 10,000 million drops of water. As seasonal booms in prey occur, knowing the times when sharks are likely to be arriving to feed or when they are likely to be suffering a fast, are important. The same tests showed that lemon sharks, at least, are repelled by the smell of human sweat; you may empathise! Xavier sees this as a likely explanation of some seemingly selective shark attacks as they bi-pass one person, but bite another less tangy individual.

Hmmm, get sweaty before swimming, stay quiet, don’t get injured or carry struggling fish. Beware though, other species may be attracted to sweat so selective sweating may be necessary.

Closer still to its prey, the sharks onboard equipment begins to look more like something from science fiction set in the future than a primitive being left behind by an evolving world.

Lateral thinking… the lateral line

Something peculiar to fish and equally useful to sharks is the lateral line. It is visible on many fish as a mark (like someone has scratched a key down the bodywork of a shiny car) going down the side of the body from the gill to the tail. It is not so obvious in most sharks but it’s there. If hearing is audio-reception and smell is chemo-reception, then the lateral line performs mechano-reception. Picking up any vibrations that the hearing might miss. The lateral line is composed of tiny pores, with a hair-like mechanism inside, which are sometimes compared to sonar.

But my analogy is more spidery. I feel it makes the shark more like a spider at the centre of her web, which may extend over 100 metres in all directions. But is particularly strong in a lateral plane, so, like an orb spider’s web it creates a disk shaped area of sensitivity. The shark knows something is in its web, in which direction and it also knows which way is up no matter how clear the water or how turbulent the conditions. Unlike a spider though, a shark can tilt its body to vary the effects on the lateral line. Gaining a picture of the unseen world around it.

The pits

Whilst hearing, smell and the lateral line may seem like a complete kit for finding prey and other sharks, there is still more to the shark than that. It’s body is covered with neuromasts, sometimes called pit organs. Their function is complicated for us, or me at least, to fully comprehend. It seems similar to the lateral line but, perhaps in a less lateral way.

Visual contact

The senses described so far will bring a shark within 20 metres of whatever is interesting it. This is often close enough for that point of interest to be visible. Sharks eyes vary from species to species but, on the whole, they are as comparable to the eyes of cats and other nocturnal species as they are to those of diurnal humans. They see the best of both worlds! At the back of the eye is a layer of cells called the tapetum (or tapetum lucidum). These reflect light back to the retina and so make use of all available light in dim conditions. In cats it is the tapetum that makes their eyes light up in torchlight. Sharks retinas contain rods and cones like human eyes so they can see colours too.

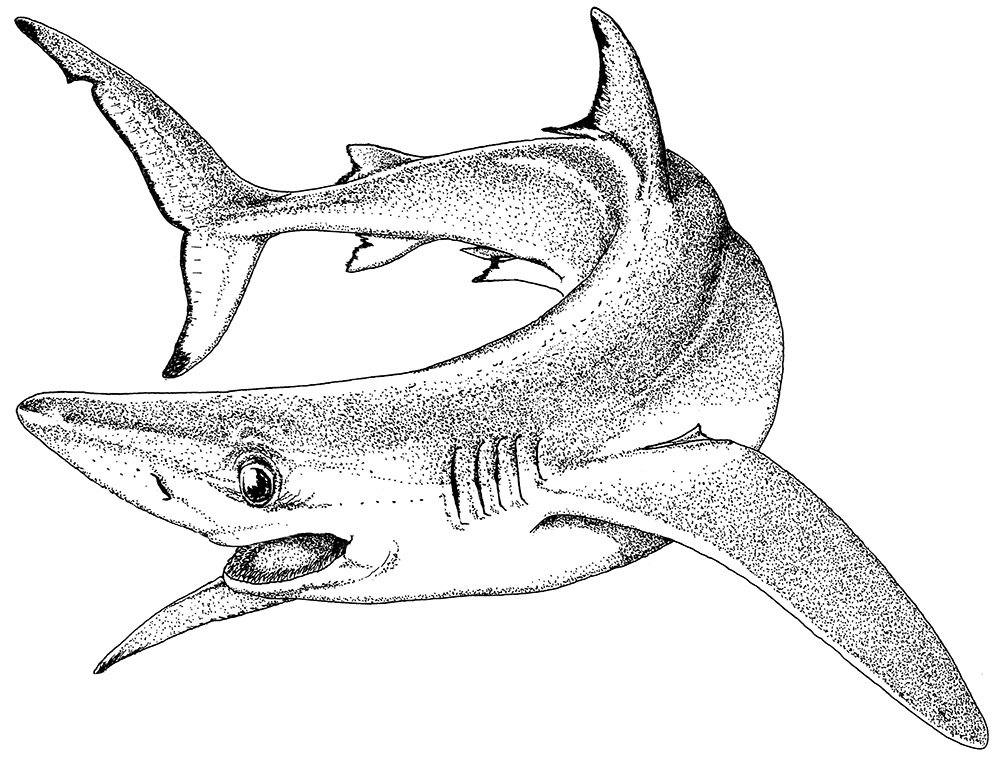

They have long had a reputation for an attraction to what we see as yellow. Xavier laments the use of yellow in life saving equipment. Interestingly cats , similar to dogs, have limited colour vision and it is blues and yellows they can most likely discern rather than red and green which they probably see as shades of grey. Some sharks, like the blue shark have nictitating membranes very similar to those in crocodiles and birds. This is a translucent eyelid that protects the eye in close contact whilst still allowing some vision. Can you feel this shark getting closer?

Can you feel my heart beating?

Coming in closer, the shark experiences the object of interest with another array of sensors called the ampullae of Lorenzini. An Ampulla was a spherical roman jug or vase which the shark’s sensors, dotted mostly beneath the nose, superficially resemble. They were first described in the late 1600s by Italian scientist Stefano Lorenzini.

In the unlikely event that all the shark’s other senses cannot detect prey or danger, if they can get within about 10cm, then the ampullae of lorenzini will sniff it out. A prime example might be a flatfish hiding beneath sand or mud in water so muddy that it is opaque. The ampullae pick up electric signals (as weak as a hundred-millionth of a volt per square centimetre) from living organisms. This could be slight muscle movements, like the blink of an eye, a visually imperceptible tensing or… a heart beating.

They are probably highly sensitive to temperature changes and salinity as well, like an instant portable aqua-lab. The signals given off weaken rapidly with distance. But also strengthen if the victim is injured. So if a shark can manage an exploratory bite, it has a much better chance of finding its original target as it wheels round for another look. The re-assuring side to this is that sharks are usually good at detecting what is not their normal food and veering away. Similarly, they are repulsed or confused by electric currents and signals from metal objects and this knowledge can be used to keep sharks away from vulnerable people.

By the teeth of their skins

Shark attacks in coastal areas are normally on a single target victim. But the record is complicated by the final element in the sharks armoury of weapons and sensors, it’s skin.

Where fish have scales, sharks have denticles. As the name suggests, denticles are very much like tiny little teeth all over the shark’s body. So the skin is like an ultra-fine nuanced armour. The denticles are embedded in the skin at their front end and point smoothly together towards the rear of the shark. Enabling very slick streamlining. It’s very much adapted for one way thinking though. Reverse gear is not a sharky thing and if you rub their skin from nose to tail it will slide along smoothly. But rub the other way and your fingers will stop dead or even be cut. Shark’s skin was used for polishing wood and other objects before sandpaper, wire wool and glass paper took over.

Something some sharks do with interesting objects in the sea is bump and rub against it to feel and sense it, a bit like cats rub their bodies on our legs but many many times more chilling if it is happening to you! Shark skin is so tough and rough that it can easily lacerate our bare skin. Some deaths during shark attacks have been rescuers lacerated by the unforgiving skin on shark fins as they hurtle in to the ‘target victim’. Some sharks use their fins, rather than their teeth, to kill or immobilise prey; thresher sharks are especially adept at this and have fins adapted to suit their skills.

The World’s most infamous gnashers

And finally (well sort of)… jaws! Many shark attacks, including fatal ones, appear to be exploratory bites which resulted in disinterest or rejection. Unfortunately the shark’s jaws are so powerful and teeth so efficient at cutting that bones may be crushed or blood loss may be too great. Especially if the victim goes into shock. Teeth in some sharks are hooked, whilst in others they are triangular and serrated like saws. Other sharks have crushing and grinding teeth for bottom living prey. The teeth are shed as they age and replaced by new sets which fold forwards from behind. So a shark is never short of teeth. One perhaps merciful mystery about shark bites is that most people bitten report a complete absence of pain during the attack.

Sharks don’t have bony skeletons, they have quite rubbery, cartilaginous ones which rarely fossilise but their teeth do fossilise. Shed teeth, adding to teeth from dead sharks are common fossils which can trace shark families back over 200 million years.

Part two

Part two of the shark blog will be much more focused on the individual species of sharks found in British waters. Coming soon! If you already love British Sharks you can buy your T-shirt now 🙂